Introduction

Vibhuti is the Sanskrit term for “power” or “manifestation.” In this third chapter with 56 sutras, Maharshi Patanjali introduces the final three limbs of Aṣhṭanga Yoga, collectively known as ‘samyama.’ Through samyama, a yogi not only gains insight into pure awareness (Purusa) but may also acquire siddhis, or extraordinary abilities, that arise as the practitioner gains mastery over the tattvas, the fundamental constituents of prakriti. However, the text also cautions that these powers can become obstacles for those seeking true liberation.

Samyama in Vibhuti Pada

Vibhuti Pada comprises Samyama which includes:

Dharana: Dharana refers to concentration, the practice of fixing the mind steadily on a single point or object. As the sixth limb of the eightfold path, it involves consciously directing attention and developing the mental discipline essential for self-realization and liberation.

Dhyana: Dhyana, or meditation, is the uninterrupted, effortless flow of attention toward the chosen object initiated in Dharana. At this stage, the mind remains continuously focused without distraction, deepening the internal stillness and preparing the practitioner for samadhi.

Samadhi: Samadhi is the

culmination of the threefold practice of samyama. It is a state of profound

absorption in which the distinction between the meditator and the object

dissolves, giving rise to pure awareness. This transformative state is

sometimes described as “seedless absorption.”

Samyama in Ashtanga Yoga

The combined practice of the last three limbs of Ashtanga Yoga, that are Dharaṇa, Dhyana, and Samadhi, focused on a single object is called Saṃyama. According to Maharshi Patanjali, Saṃyama means practicing all the three limbs of Dharaṇa, Dhyana, and Samadhi on the same object, place, or point of focus. Only through proper mastery of these three, applied together, does one attain the intended result.

Fruit of Samyama: When Saṃyama is perfected, the tamas and rajas qualities of the mind diminish, and sattva becomes predominant, giving rise to a higher form of knowledge. To sustain this refined state of mind, the practitioner must continue the practice of Saṃyama with consistency and steadfastness.

After gaining the special insight that arises from Samyama, the practitioner naturally perceives the next stage of yoga that lies before him. If he bypasses the immediate stage and attempts to apply Samyama to more advanced states, obstacles will inevitably appear on the yogic path.

Internal or Antaranga Sadhana: According to the Sutras, Dharaṇa, Dhyana, and Samadhi are considered internal means or Antaranga Sadhana in relation to Yama, Niyama, Asana, Praṇayama, and Pratyahara. Internal means subtler or finer forms of sadhana.

External or Bahiranga Sadhana: From the perspective of Nirbija Samadhi, termed as ‘Asaṃprajnata Samadhi’ in yoga, these three (dhyana, dharna, samadhi) become external means or Bahiranga Sadhana. For Nirbija Samadhi, the practice in the form of Para Vairagya or supreme dispassion, becomes the internal means. This is the innermost or finer state of samadhi without object or seed. Only pure awareness exists.

Nirodha Parinama

The mind is described as resting on five kinds of grounds or bhumis:

When the mind reaches the Ekagra bhumi and the aspirant continues yogic practice, it may still fluctuate due to impressions from past lives. At times, helpful impressions known as nirodha saṃskaras (restraining impressions) arise; at other times, harmful impressions called vyutthana saṃskaras (outgoing or distracting impressions) appear. The alternation of the mind between Nirodha saṃskaras and Vyutthana saṃskaras constitutes the transformation (pariṇama) of the mind (chitta).

Fruits of Nirodha Parinama: When the Vyutthana-saṃskaras

(distracting impressions) are subdued and the Nirodha-saṃskaras (restraining

impressions) arise in the mind and continue for a long time in an unbroken

flow, then the mind becomes completely calm and serene. Attaining Nirodha

Parinama, makes the mind or chitta, spotless and pure, helping the yogi enters

a higher state of yoga.

Samadhi Parinama

With sustained practice of Nirodha Parinama, the state of samadhi arises—not abruptly, but gradually, through long and disciplined effort. This unfolding occurs through the continued practice of samyama, wherein dharaṇa matures into dhyana, and dhyana, in turn, transforms into samadhi.

As the yogi observes subtle changes in the mind, such as

growing inclination toward the peace experienced in a state of inner stillness,

he recognizes this as a sign of progress. This “void” is neither of the

external world nor of the subtle realms; rather, it is a void within the psyche

itself. In this state, memory ceases to release impressions that erupt into

chains of ideas, triggering further thoughts that disturb the mind. In this

state, the yogi is no longer tormented or frustrated in his pursuit of mastery

over the psyche.

Ekagrata Parinama

When the yogi reaches a stage where mental activity is no

longer governed by memory, attention can be held in a calm and settled

condition. This state endures only as long as the restraining thoughts of the

mind remain disconnected from memory. While the mind’s natural tendency to

arise and subside cannot be altered, the yogi can find temporary respite by

directing awareness toward subtler dimensions and by stilling mental motion

through the practice of praṇayama.

The technique applied at this stage involves fixing attention on a subtle inner sound arising from the chit akasa. As the yogi perceives this sound, attention is simultaneously focused on a diffused light appearing before him, cultivating ekagrata. At this point, there is no external visual object for the mind to grasp. The diffused light, initially blended with a cloudy or mist-like energy, is gradually refined, as the obscuring element dissolves and only pure light remains. When the yogi stabilizes in this practice, he has mastered the seventh stage of yoga, known as dhyana.

Application of Parinamas: In this yogic discipline,

both subtle and gross material energies are systematically addressed as the

yogi strives to bring the psyche under mastery. The essence of this effort lies

in cultivating complete detachment from these gross and subtle forces. It is the

habitual reaction to mundane energies that leads to the downfall. When one

learns to regulate this response and ultimately to relinquish it entirely, the

control so earnestly sought is finally attained.

Dharmi or The Common Substratum

Dharmi is often referred to the energy of prakriti or the most subtle form of material nature. However, for a yogi, it is the technique to completely abandon the energy of prakriti and achieve complete detachment. The technique is to focus within his psyche or to the ultimate substratum. Once he masters the technique of dharmi, he becomes liberated. The result of the dharmi changes when there is a difference in the sequence (krama) of the substance. Here, krama means the state or condition of the substance. As the state of the substance changes, its result will also change accordingly.

Cause of the change: Body, mind, intellect, heart,

and soul, are like substances in which, over time, good and bad changes occur. It

is important to understand how these changes, when supported and shaped by

yogic practices, help sadhana progress. Through meditation and devotional

singing, corresponding results will start manifesting in the mind, intellect,

heart, and soul. However, the results change according to the sequence of

practice.

Vibhutis Achieved by Practicing Samyama

In the Vibhuti Pada, the term vibhuti signifies “powers” or “extraordinary abilities.” It is from this meaning that the third chapter derives its name, Vibhuti Pada. After the yogi masters dharmi and achieves complete detachment, his mind gains liberation from the energy of prakriti. At this point, he experiences extraordinary powers or achieves vibhutis.

Knowledge of Past and Future: With a clear intellect and continuous practice of dharna, dhyana, and samadhi, the yogi gains knowledge of the past and future of any object.

Knowledge of all Speech: The knowledge of any object or entity is gained in three ways- name (Sabda), meaning (Artha), and the knowledge generated with both name and meaning- called pratyaya. Once samyama is perfected, the yogi gains respective knowledge of all words, their meanings, and the knowledge they convey.

Knowledge of Previous Births: By applying samyama his own samskaras (mental impressions), he begins to know his previous births. Here, the yogi becomes aware of the species or form of existence he occupied in all his past lives.

Knowledge of Others' Minds: By practicing dharaṇa, dhyana, and samadhi together with firmness upon another person’s mind, the yogi comes to know about their emotions and samskaras operating within their psyche. Although the yogi gains knowledge about the emotions arising in another person’s mind, he will not know about the object towards which the person has such feelings or emotions.

Invisibility: The yogi gains the power of antardhana or the ability to become invisible by applying samyama. With constant practice of dharna, dhyana, and samadhi on his own body, he can cause his own form to disappear.

Disappearance of the tanmatras: There are five Tanmatras or sensory experiences- Shabda, Sparsha, Rupa, Rasa, Gandha in correspondence to five Mahabhutas or gross elements of nature- earth, water, fire, air, and space. By practicing samyama with dedication, the yogi can restrain sound and the related sensual pursuits, resulting in the related non -perceptibility.

Knowledge of time of death: By restraining the mental and emotional energy in relation to the confusing impressions or samskaras, the yogi derives intuitive or direct supernatural perceptions into the subtle world. He will have the knowledge of a person’s death or re-birth. A yogi can leave his body and enter other dimensions.

Powers of friendliness: When the yogi detaches himself from the cultural prejudices, which were cultivated in the present and past lives, he develops universal friendliness. He applies this friendliness without biases which come up from the subconscious memory as predispositions.

Attainment of Strength: With complete restraint over the mind, the yogi achieves the strength of an elephant, both physically and mentally.

Hidden Knowledge: From the application of supernatural insight to the force producing cultural activities, a yogi gets information about what is subtle, concealed, and what is remote from him.

Knowledge of the Solar System: In this state, the yogi gains complete knowledge of the Sun and the entire planetary system.

Knowledge of the Stars: The yogi gains knowledge about the moon and all other stars in the space. At his point, he can even predict the movement and course of planets and stars in reference to the pole star.

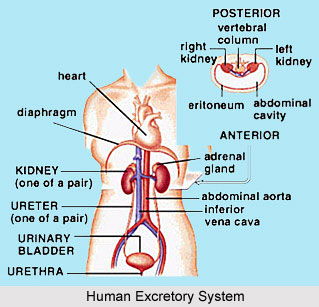

Knowledge of the Body: By practicing samyama with a keen focus on his navel, the energy-gyrating center of his body, the yogi gains complete knowledge about the layout of his body.

Cessation of Hunger and Thirst: By restraining his energy and focusing on the gullet, a yogi causes the suppression of hunger and thirst.

Power of Steadiness: By focusing his energy on the kurmanadi subtle nerve, the yogi acquires steadiness of his psyche. The kurmanadi is supposed to be located below the gullet.

Spiritual Vision: By focusing relentlessly on the shining light in the head of the subtle body, a yogi gains spiritual vision, through which he can perceive perfected beings.

Intuitive Knowledge: By completely restraining all energy, while focusing on the shining organ of divination in the head of the subtle body, the yogi gets the ability to know all reality.

Awareness of Chitta: By completely restraining the mind while it is focused on the causal body in the vicinity of the chest, the yogi gets insight into the cause of the mental and emotional energy.

Knowledge of Purusha: The yogi can clearly distinguish between buddhi and puruṣha and then performs the combined practice of dharaṇa, dhyana, and samadhi solely on puruṣha. With this, he not only attains the knowledge of puruṣha, but also acquires six distinct supernatural powers (siddhis).

Intuitive Perception: The yogi can produce the sense of smelling, tasting, seeing, Touching, and hearing, through the shining organ of divination without any physical involvement.

Caution: Siddhis or Psychic Powers are Obstacles

These divine powers can be obstacles in Samyama if the yogi

is distracted by these supernatural abilities which are manifested as he

progresses in the path of yoga. If the yogi cannot resist exhibiting such

powers, his progress will be stalled and become more difficult.

Other Vibhutis

If the yogi manages to use or apply the vibhutis or siddhis in the right path then he achieves higher divine powers.

Entering Another’s Body: The yogi can enter another person’s body by slackening the cause of bondage. He can gain complete knowledge of the other person’s mental and emotional energy channels through this method.

Levitation: With mastery over the air which rises from the throat into the head, a yogi can rise over the surface of earth, or not have contact with water, mud or sharp objects.

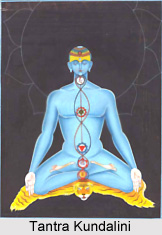

Aura: By mastering samana digestive force, a yogi’s psyche blazes or shines with a fiery glow. This energy generated from the frontal kundalini then creates a fiery glow around his subtle body which is called Aura.

Divine Hearing: By restraining his emotional and mental energy while focusing on the sense of hearing and space, a yogi develops supernatural and divine hearing abilities.

Moving through space: With higher level of concentration, a yogi can connect with space, turn his mind lighter than cotton fluff. With this ability, he can pass through atmosphere.

Universal State of mind: With constant practice of Samyama, a yogi’s concentration becomes so powerful that the mind can be outside even while remaining in the body, and the mind can also travel outside the body. This is described as the power of the universal state of mind, as the mind is subtle, and it alone is capable of such movement.

Mastery of the Bhutas: The yogi attains mastery over five mahabhutas- Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space.

Attainment of Anima: With complete control over the five mahabhutas, the yogi gains special physical powers along with the eight siddhis beginning with Aṇima. Moreover, the five great elements no longer create any obstacle for the yogi, because they have been brought under control and can no longer cause any harm.

Perfection of the Body: With the attainment of the eight siddhis beginning with Aṇima, a special power also manifests in the yogi’s body. He attains five special bodily excellences such as form, grace, strength, and vajra-samhanana (adamantine hardness).

Mastery of Sense Organs: With this extraordinary bodily power, the yogi can perform samyama over five different types of senses can achieve complete control over them. They are Grahana (Reception), Svarupa (Form), Asmita (Identity), Anvaya (Inherence), and Arthavattva (Purpose).

Conquest of Prakriti: With the combined energy of dharaṇa, dhyana, and samadhi upon the senses and their states, the yogi begins to acquire three types of siddhis: manojavitva, vikaraṇa-bhava, and pradhana-jaya. Manojavitva means attaining swiftness of the mind. With vikaraṇa-bhava, his mind can operate outside the body and with pradhana-jaya he conquers prakriti itself and all the subtle matter in it.

Omnipotence and Omniscience: With mastery over five senses and five mahabhuas, the yogi clearly understands or directly experiences the distinction between purusha (the Self) and sattva. With this knowledge, all substances in the entire prakṛti (nature) come under his control which is omnipotence. He achieves full disaffection from the subtle influence of material nature and attains all-applicative intuition which is omniscience.

Vairagya and Knowledge: Even if a yogi’s material

body leaves the world, a yogi should be non-responsive, not desiring in their

association. The yogi should practice complete detachment. He should not be

fascinated by his knowledge or siddhis,

otherwise that would cause unwanted features of existence to arise again.

Caution: Causes of Downfall

Maharshi Patanjali offers a clear warning to the yogi, after they have attained powers. Their siddhis must be used with utmost care, not for personal display or self-importance, but solely for the welfare of all, and only when truly necessary. These powers should be exercised with complete humility. Even then, the danger remains that pride or a sense of superiority may arise from possessing such abilities. Those around the yogi can also become sources of ego, attachment (raga), and aversion (dvesa).

When these powers are displayed, fame may spread, drawing the attention of influential individuals and institutions. These influences pose a real risk of causing a fall from the path. If that happens, the yogi may need to begin his practice anew and the journey will be far more difficult. It is even possible that he may not recognize that he has strayed from the path at all.

Awareness of Reality: When the yogi performs samyama on the subtle unit of time, which Maharshi refers to as the kṣaṇa (moment), he attains viveka-jnana—discriminative knowledge. Moments arise one after another, and when the yogi applies concentration (dharaṇa), meditation (dhyana), and absorption (samadhi) together on the transition between two successive moments, he perceives with clarity the distinction between truth and untruth, right and wrong, duty and non-duty, injunction and prohibition. In this way, he firmly steps onto the path of liberation.

Knowledge of Distinctions: When it becomes difficult to distinguish an object or substance by its species (jati), characteristic (lakṣaṇa), or location (sthana), it is through viveka-jnana that these differences become clear. This discerning ability belongs only to the yogi who has attained such knowledge.

Transcendental Knowledge: This is where the yogi

reaches the culmination point of yoga where he can assess his progress himself

and learn where and when he can attain kaivalya, crossing over the mundane

reality of life which keeps him so occupied even when he tries to transcend it.

Attainment of Kaivalya

As the yogi steadily progresses along the path of practice, purifying both the individual soul (jivatman) and the intellect (buddhi), he ultimately attains Kaivalya—the state of absolute aloneness. When there is equal purity between the intelligence energy, material nature and the spiritual self, then total separation happens between purusha and prakriti. This state is referred to as Kaivalya.

According to Maharshi Patanjali, when the yogi fully

realizes the complete distinction between buddhi and purusha, a transformative

stage arises where buddhi transcends the guṇas. Through this

transcendence, purusha is revealed in its flawless purity.