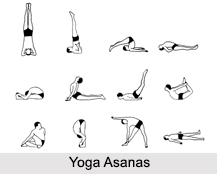

The fourteenth yogic sutra speaks about the latent features of nature and its qualities. The various facets appear according to an individual`s rational development. However, the substratum remains unaffected. Consciousness is the major factor here, with its several stages of one-pointedness, all-pointedness, rising and subsiding thoughts. A tranquil state can only be achieved when these upheaving thoughts can be pacified. `Stress` or `strain` is always calmed down when one practices the art of asana, pranayama or meditation. A sadhaka can attain self-realisation, if he is able to differentiate between true knowledge and dichotomy.

The fourteenth yogic sutra speaks about the latent features of nature and its qualities. The various facets appear according to an individual`s rational development. However, the substratum remains unaffected. Consciousness is the major factor here, with its several stages of one-pointedness, all-pointedness, rising and subsiding thoughts. A tranquil state can only be achieved when these upheaving thoughts can be pacified. `Stress` or `strain` is always calmed down when one practices the art of asana, pranayama or meditation. A sadhaka can attain self-realisation, if he is able to differentiate between true knowledge and dichotomy.

santa appeased, allayed, calmed, quietened, pacified

udita rise, ascended, manifested

avyapadesya not defined, latent, lying in potential form

dharma propriety, usage, law, duty, religion, virtue

anupati closely followed, common to

dharmi virtuous, just, religious, characterised

The substratum is that which continues to exist and maintain its characteristic quality in all states, whether manifest, latent, or subdued.

The integral characteristic quality of nature (mula-prakrti) has three properties - pacified or calmed (santa), manifested (udita) or latent (avyapadesa). They appear indistinctly or clearly, according to one`s intellectual development.

The substratum of nature remains the same for all time, though transformations take place. The moulding of consciousness takes place owing to the changes in the gunas of nature.

Patanjali explains the three phases of consciousness as rising, being restrained and the pauses between the two. In III.10, he describes these pauses as tranquil consciousness. If these pauses are prolonged, all pointedness and one-pointedness meet, and there is no room for rising or subsiding of thoughts Sutra 12 explains that maintaining these quiet moments gives rise to a balanced state of consciousness, which is described in III. 13 as a cultured and harmonious state. Rising and restraining thoughts are the inclinations (dharma) of the citta, and the tranquil state is its characteristic quality (dharmi).

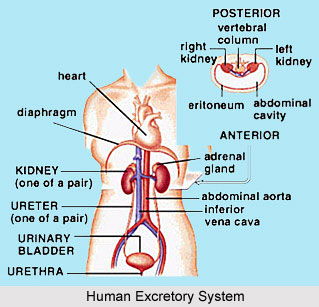

The rising citta is felt in the sensory body. Citta then appears at the external level as bahirahga citta. Watching the movement of rising thoughts is an external or bahirahga sadhana. The delicate restraint of rising thoughts moves citta inwards from the peripheral body - this is inner or antarahga sadhana. Stabilising the tranquillity that takes place in the intervals is innermost or antaratma sadhana - that state is considered to be an auspicious moment of consciousness. It is like re-discovering the dust, which existed before the pot.

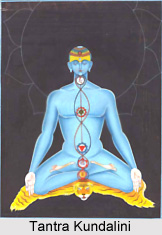

It is explained that consciousness has three phases - external, internal and innermost. As one traces and retraces these, their relevance can be noticed to an individual`s practices of asana, pranayama and meditation, in which consciousness moves from the skin inwards, and each cell and fibre is infused with the tranquillity of the seer.

It is explained that consciousness has three phases - external, internal and innermost. As one traces and retraces these, their relevance can be noticed to an individual`s practices of asana, pranayama and meditation, in which consciousness moves from the skin inwards, and each cell and fibre is infused with the tranquillity of the seer.

Today, everyone is aware of constant `stress and strain` in life. These aspects of consciousness which confuses life are by no means new to mankind. Patanjali`s word vyutthana, used to designate the `emergence of rising thought`, is equivalent to the appearance of `stress`. Nirodha, `restraint of rising thought` is equivalent to the `strain` of trying to control that stress. Striking the balance between the two is called `relaxation` (santi citta). Restraining of rising thought is against the current (pratipaksa). Hence restraint is strain.

A person who has undergone childhood is santa, because that childhood stage has passed and is over. As one stands at the threshold of youth, he is in the present or udita state. In course of time, one moves towards old age, which is yet to come - this is avyapadesya, old age which is still in an unmanifested form and indistinct. But the person remains the same through all these changes. That unchanging person is dharmi. Likewise, milk is the property which separates into curds and whey, or changes into butter. It is the same with dust, which is formed into clay to make a jar. The dust stands for the past, the clay for the present, the jar for the future. Thus every change from the source move in time as past, present and future.

In II.18, the properties of nature are explained as luminosity (prakasa), vibrancy (kriya) and inertia (sthithi). By the use of these qualities, one may be entangled in a mixture of pleasure and pain, or go beyond them to unalloyed bliss.

The properties of nature exist for the purpose of one`s evolution and involution. Consciousness, being a part of nature, is bound by the spokes of the wheel of time.

If an aspirer sows the right seed through knowledge and discrimination (viveka) and develops consciousness, he reaps the fruit of self-realisation through ekagrata. He becomes the force which severalises between the hidden properties and the transformations of nature. He recognises his true, pure state of existence which is changeless and virtuous. This is the fruit earned through the astute effort of sadhana.

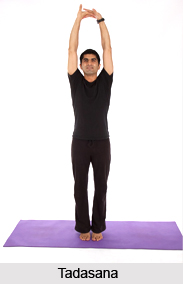

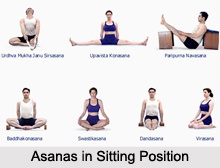

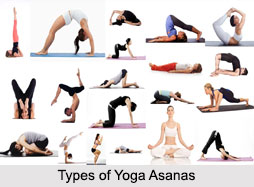

The import of this sutra can be used to practical advantage while practising asana, pranayama or meditation. If one observes the various scattered cells dust lying latent in the body, and charge them so that they adhere (lump of clay), one can feel the inner unity and transform body, breath and consciousness into designs in the form of different asanas and pranayamas, as the potter moulds his clay into a variety of shapes.

In asana, if the energy of the body is reconciled to a `point zero`, while in a state of tension, one accomplishes exactness. The same can be applied to the intake of breath, its distribution or discharge in pranayama, and in meditation. The combining of single-pointed attention with all-pointed attention at the core of one`s being is the essence of this sutra.

`Point zero` designates the point of balance and harmony at which one can unlock and liberate the problematic confusion of matter and emotion. It also expresses the importance of finding the exact centre of the meeting points of vertical extension and horizontal expansion in body, breath and consciousness.