The thirty-fourth yoga sutra states about the ultimate state of kaivalya, and the long path by which one can reach it. Patanjali explains that it is immensely necessary to pass through the fourfold stage of purusarthas - dharma, artha, kama and moksa. He also has to transcend the gunas (the several qualities of human nature) and aims, which after kaivalya, returns to its source. The consciousness, finally establishes itself in its own glory. These, though cannot be attained by mere practice, one needs to be virtuous in his pranayama, asana and dhyana. At this point of realisation, the yogi realises that the seeker, the seer and the instrument used to understand the seer is atman. This absoluteness of consciousness is nothing but the seer.

purusartha fourfold aims of man - discharging one`s duties and

obligations to oneself, one`s family, society and country

(dharma); pursuit of vocation or profession, following

one`s means of livelihood and acquisition of wealth

(artha); cultured and artistic pursuits, love and

gratification of desires (kama); emancipation or liberation

from worldly life (moksa)

sunyanam devoid of

gunanam of the three fundamental qualities

pratiprasavah involution, re-absorption, going back into the original form

kaivalvam liberation, emancipation, beatitude

svarupa in one`s own nature

praiistha establishment, installation, consecration, completion

va or

citisaktih the power of pure consciousness

iti that is all

Kaivalya, liberation, comes when the yogi has fulfilled the purusarthas, the fourfold aims of life, and has transcended the gunas.

The yogi with the stream of virtuous knowledge is devoid of all aims of life as he is free from the qualities of nature. Purusarthas are man`s four aims in life - dharma (science of duty), artha (purpose and means of life), kama (enjoyments of life) and moksa (freedom from worldly pleasures). They leave the fulfilled seer and fuse in nature.

Patanjali speaks of the purusarthas only in the very last sutra. This may baffle the aspirer. Patanjali is an immortal being, who had accepted human incarnation with its joys and sorrows, attachments and aversions, in order to live through emotional upheavals and intellectual weaknesses to help mankind overcome these obstacles and travel in the direction of freedom. Awareness of the aims of Life may have been unconsciously hidden in his heart, to surface only at the end of his work. But his thoughts on the purusarthas are implicitly contained in the earlier chapters, and expressed clearly at the end. Thus, the four padas are, consciously or unconsciously, founded on these four aims and stages of activity.

Dharma is the careful observation of one`s ethical, social, intellectual and religious duties in daily Life. Strictly stating, this is taught at the level of studentship, but it must be followed throughout life; without this religious quality in daily life, spiritual attainment is not possible.

Artha is acquisition of wealth in order to progress towards higher pursuits of life including understanding the main purpose of life. If one does not earn one`s own way, dependence on another will lead to a parasitic life. One should never be greedy while accumulating wealth, but only to meet one`s needs, so that one`s body is kept nurtured and one may be free from worries and anxieties. In this stage one also finds a partner with whom to lead a householder`s life. One comes to understand human love through individual friendship and compassion, so that one may later develop a universal fellowship leading to the realisation of divine love. The householder is expected to satisfy his responsibilities of bringing up his children and helping his fellow men. Thus, married life has never been considered a hindrance to happiness, to divine love or to the union with the Supreme Soul.

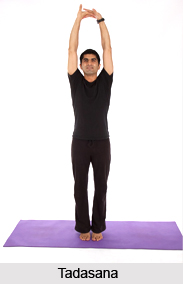

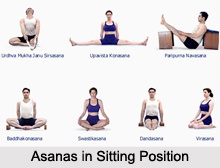

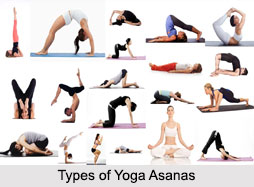

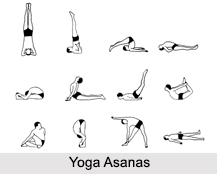

Kama means enjoyment of the pleasures of life, provided one does not lose physical health, or harmony and balance of mind. The Self cannot be experienced by a weakling, and the body, the temple of the soul, has to be treated with care and respect. Asana, pranayama and dhyana, therefore, are essential to purify the body, stabilise the mind and clarify the intelligence. One must learn to use the body as a bow, and asana, pranayama and dhyana as arrows to be aimed at the target - the seer or the soul.

Moksa means liberation, freedom from the bondage of worldly pleasures. It is the experience of emancipation and beatitude, possible only when one is free from physical, psychological, intellectual and environmental afflictions (1.30-31), and from poverty, ignorance and pride. In this state one realises that power, knowledge, wealth and pleasure are merely passing phases. Each individual has to work hard to free himself from the qualities of nature (gunas) in order to master them and become a gunahtan. This is the very essence of life, a state of indivisible, infinite, full, unalloyed bliss.

These aims involve virtuous actions and are linked with the qualities of nature and the growth of consciousness. When the goal of freedom is attained, the restricting qualities of consciousness and nature cease to exist. At this point of fulfilment, the yogi realises that the seeker, the seer and the instrument used to cognise the seer is atman. This absoluteness of consciousness is nothing but the seer. Now, he is established in his own nature. This is kaivalyavastha.

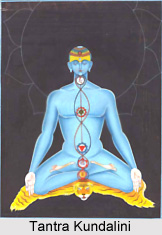

The practice of yoga serves every aim of life. Through the proper use of the organs of action, senses of perception, mind, ego, intelligence and consciousness, their purpose of serving their Lord, the seer, comes to an end, and these vestments of the seer, along with the qualities of nature, coil and withdraw, to unite in the root of nature (miila-prakrti).

There, they are held and isolated. By this, the citta becomes pure and supreme. In this supreme state, citta divinely merges in the abode of the seer so that the seer can shine forth in his immaculate, pure and untarnished state of aloneness. Now, the yogi shines as a king amongst men. He is crowned with spiritual wisdom. He is a krtarthan - a fulfilled soul, who has learned to control the property of nature. He brings purity of intelligence (in.56) into himself. He is now free from the rhythmic mutation of gunas, of time, and thus released from aims and objects, as his search for the soul ends. All the twenty-four principles of nature (II.19) move back into nature and the twenty-fifth, the seer, stands alone, in kaivalyam. He is one without a second; he lives in benevolent freedom and beatitude. With this power of pure consciousness, citta shakti, he surrenders completely to the seed of all seers, Paramatma or God.

Lord Krishna, in the Bhagavad Gita (XVIII.6I-62), explains that `the Supreme Ruler abides in the hearts of all beings and guides them, mounting them on wheels of knowledge should seek refuge by surrendering all actions as well as himself to the Supreme Spirit or God` so that he journeys from Self-Realisation towards God-Realisation.

Patanjali began the journey towards the spiritual kingdom with the word atha, meaning `now`. He ends with the word iti, meaning `that is all`. The yogi has reached his goal.

Here ends the exposition of kaivalya, the fourth pada of Patanjali`s Yoga Sutras.