The term `ikat` steams from the Malay Indonesian expression mangikat, meaning to bind, knot or wind around. Ikat ,known as tie and dye textile design, is known around the world. Some experts are of the opinion that the technology came from far eastern countries but actually the name was given to the technique by Indonesians. But study reveals that it started and developed in India also at least in certain clusters like Orissa, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh and upto certain extent in north, east and north eastern India. Ikat is equivalent of the Indian bandhana.

The term `ikat` steams from the Malay Indonesian expression mangikat, meaning to bind, knot or wind around. Ikat ,known as tie and dye textile design, is known around the world. Some experts are of the opinion that the technology came from far eastern countries but actually the name was given to the technique by Indonesians. But study reveals that it started and developed in India also at least in certain clusters like Orissa, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh and upto certain extent in north, east and north eastern India. Ikat is equivalent of the Indian bandhana.

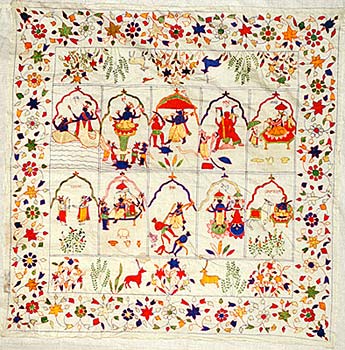

Orissa has a patola style of its own. The designs usually are in floral patterns, with animals and certain traditional motifs like fish conch. The cotton ikats in Orissa are fabulous with firm accent on the geometrical patterns in heavy waves. One of the most popular motifs used in the fabrics is the Gaja (elephant) particularly in Khandua (odhni) used by brides at marriage time. Large and small stars, elephant, deer, parrot, nabagunjara, lotus and other flowers, creeper, kumbha (small triangles), danti (tooth-like) patterns have been used in silk and cotton fabrics.

Orissa has a patola style of its own. The designs usually are in floral patterns, with animals and certain traditional motifs like fish conch. The cotton ikats in Orissa are fabulous with firm accent on the geometrical patterns in heavy waves. One of the most popular motifs used in the fabrics is the Gaja (elephant) particularly in Khandua (odhni) used by brides at marriage time. Large and small stars, elephant, deer, parrot, nabagunjara, lotus and other flowers, creeper, kumbha (small triangles), danti (tooth-like) patterns have been used in silk and cotton fabrics.

Procedure of making Ikat Fabrics

In principle, ikat or resist dying involves the sequence of typing (or wrapping) and dyeing sections of bundles yarn to a predetermined colour scheme prior to weaving. Thus, the dye penetrates into the exposed sections, while the tied sections remain undyed. The patterns formed by this process on the yarn are then woven into fabrics. In ikat technique, which is also called tie and dye technique, the designs in various colours are formed on a fabrics either by warp threads or weft threads (single ikat) or by both (double ikat). In single ikat fabrics, the warp or weft threads which are tied and dyed as per design are to be positioned accurately in proper sequence in weaving as required by the design and colour scheme.

In case of double ikat fabrics, not only warp and weft threads which are tied and dyed as per design should be individually positioned in proper sequence, but the relative position of each warp threads and weft thread forming the design should be accurately ensured. In these textile, forms are deliberately feathered so that their edges appear hazy and fragile. This effect is achieved by the use of very fine count yarn, tied and dyed in very small sets. In tie and dye process, increased number of colours used in bringing out figures increases the number of tying and dyeing. If the designs are all over and connected with each other in some way, by tie and dye links, all the picks in fabric may have to be tied and dyed.

In case of double ikat fabrics, not only warp and weft threads which are tied and dyed as per design should be individually positioned in proper sequence, but the relative position of each warp threads and weft thread forming the design should be accurately ensured. In these textile, forms are deliberately feathered so that their edges appear hazy and fragile. This effect is achieved by the use of very fine count yarn, tied and dyed in very small sets. In tie and dye process, increased number of colours used in bringing out figures increases the number of tying and dyeing. If the designs are all over and connected with each other in some way, by tie and dye links, all the picks in fabric may have to be tied and dyed.

Ikat, the technique by which the warp or weft or both can be tie-dyed in such a way that when woven, the `programmed` pattern appears in the finished fabric. Of resist-dye techniques, the use of clay or wax-resist has long been known to Indian textile printers and painters, who would stamp or delineate the fabric with resist and then immerse and re-immerse in dye. To reserve areas of the warp or weft or both, before the process of weaving with tied threads, and then to dye the yarn, is a more interesting process that requires greater skill.

And this seems to be more closely aligned to processes of tie-resist and warp-resist after weaving, than to the application of impression of a resist to the surface of a fabric.

And this seems to be more closely aligned to processes of tie-resist and warp-resist after weaving, than to the application of impression of a resist to the surface of a fabric.

Up to the beginning of this century, Chirala in Andhra Pradesh was renowned for an exquisite type of cotton sari, lungi, rumal and yardage in a range of Ikat techniques. One of the products of this place is known as telia rumal, a many-purpose cloth used as lungi, loin-cloth, shoulder-cloth and turban cloth which was a popular import item in many Islamic countries. Due to the heavy use of tel (oil), in the process of preparing the yarn for weaving, this variety of textile has deserved the name telia, meaning `oily`. The techniques and designs of telia rumal have been adapted to make saris, spreads, and yardage material.