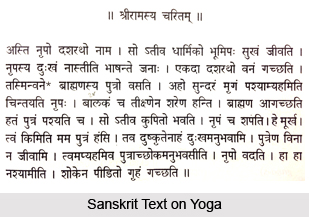

Indian texts have frequently referred to Yoga in general and Yoga Asanas in particular in several contexts. Several special Indian texts have been written and compiled with the sole purpose of educating practitioners about the practice of Yoga Asanas.

Indian texts have frequently referred to Yoga in general and Yoga Asanas in particular in several contexts. Several special Indian texts have been written and compiled with the sole purpose of educating practitioners about the practice of Yoga Asanas.

Yoga Asanas were first recorded in the Atharva Veda (1500 BCE), which uses the term asana in a specifically Yogic context. There are various other references in the Brahmanas and Upanishads which indicate that asanas must have already been in existence prior to their being noted in these textual references. Several Yogis spanning many generations scrutinized their relative merits by analytical comparisons and thus formulated a complete course of posture training. A few early postures, mostly meditative, in turn passed through a series of modifications before the whole system of physical education was finally perfected by the early Hatha Yogins.

Later Yoga treatises like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and the Yoga Upanisads provided detailed descriptions of several specific Yoga Asanas. The consistency of some postures like the Padmasana and Siddhasana, which have remained unchanged for at least a thousand years, is attributable entirely to this strong textual and oral tradition. All these texts also stressed the centrality of asanas to Yogic praxis, tying them firmly to other Yogic conventions. Amongst these texts, some stand out as highly significant within the Yoga tradition considering that later treatises consistently referred back to them as their primary sources. The following recounts the steady accretion of detail around the theory and praxis of Asanas.

Yoga Asanas in Early Indian Texts (1500 BCE - 200 BCE)

Yoga Asanas in early Indian texts were referred to in a general manner, without detailing any special poses, until the seminal Yoga Yajnvalkya, compiled around 200 BC, whose descriptions were used by works compiled as late as the 19th century CE.

Early works like the Atharva Veda Samhita (1500 BCE) and the Patanajali Yoga Sutra (600 BCE) mentioned asanas in general as postures conducive to spiritual development. The Mahabharata (400 BC) mentions two specific asanas, without description: Mandukasana and Virasana. Although Patanjali does not mention specific asanas, it is the first text to identify right posture or Asanas as part of Yogic discipline. Indeed, Asanas in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali form the third limb of Ashtanga Yoga.

Early works like the Atharva Veda Samhita (1500 BCE) and the Patanajali Yoga Sutra (600 BCE) mentioned asanas in general as postures conducive to spiritual development. The Mahabharata (400 BC) mentions two specific asanas, without description: Mandukasana and Virasana. Although Patanjali does not mention specific asanas, it is the first text to identify right posture or Asanas as part of Yogic discipline. Indeed, Asanas in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali form the third limb of Ashtanga Yoga.

The first significant step towards providing a detailed description of asanas was taken by the sage Yajnavalkya, who described several enduring meditative asanas like Padmasana, Simhasana and Mayurasana in his seminal text, the Yoga Yajnavalkya (200 BCE). Yajnvalkya also classified Asanas as meditative or cultural.

Asanas in Later Indian Texts (300 AD - 20th Century CE)

Asanas in later Indian texts formed an integral part of Yoga and several major treatises of the later period are veritable compendia of Asanas. They also found mention in several Indian philosophical texts, firmly establishing them to be part of Indian thought as a whole. The trend of building upon a select handful of meditative postures to create a physical culture is clearly visible in the later period.

The Indian Puranas (300 CE to 1000 CE) referred frequently to several meditative Asanas, notably the Ardha, Padma and Swastika Asanas. Some Puranas, such as the Visnudharmottara Purana and the Brahma Purana, also described some of these. The Gorakhsha Samhita, considered the oldest extant text dedicated to Hatha Yoga, provided instructions on performing the Padma Asana and Siddha Asana.

The Goraksha Samhita`s postures were built upon by the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (1400 CE) which describes over a dozen Asanas, with information also on how to perform them, and the ideal external conditions for practicing Yoga. These texts establish Hatha Yoga`s primacy in the Yogic tradition, especially considering that the twenty Yoga Upanishads that followed continued to list asanas attributed to the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and the Goraksha Samhita. Some of the asanas were however described according to the Yoga Yajnavalkya, reinforcing the work`s enduring influence on Asana practice.

Later works like the Gheranda Samhita (1800 CE) and `Asanas` (1926 CE) added and thereby became part of the well established Yogic `canon` (comprising the texts before the common era, the later Hatha Yogic treatises and the Yoga Upanishads) while describing asanas.

Two trends can be observed from this account: Yoga Asanas were frequently referred to in more general works (like the Puranas, the Itihasas and even the Vedas), followed by more specific and focused manuals dealing with the performance of Yoga and Yoga Asanas. Also, the asanas mentioned by general treatises are frequently meditative poses, which the Yogins built upon in the specific manuals.

These trends indicate a symbiotic relationship between Indian spiritualism and the practice of Yoga Asanas: the early practitioners of meditation devised a few stable postures, and Yogins built upon these postures to create a more general physical culture indicated by the `cultural asanas`.