Zebunissa was the first-born of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and the granddaughter of the Emperor Shah Jahan. She had also descended from the royal family of Persia, the Safavids, on her mother, Dilras Begum`s side. The eldest and favourite daughter of Aurangzeb, the last Great Mughal, she was beautiful, educated, and witty, a Sufi initiate patron of poets and philosophers, and a collector of books. Though not much has been written about her, some biographers have attempted to put together knowledge about the princess and the kind of life she must have led, the daughter of a great Mughal Emperor and a Mughal Princess.

Zebunissa was the first-born of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and the granddaughter of the Emperor Shah Jahan. She had also descended from the royal family of Persia, the Safavids, on her mother, Dilras Begum`s side. The eldest and favourite daughter of Aurangzeb, the last Great Mughal, she was beautiful, educated, and witty, a Sufi initiate patron of poets and philosophers, and a collector of books. Though not much has been written about her, some biographers have attempted to put together knowledge about the princess and the kind of life she must have led, the daughter of a great Mughal Emperor and a Mughal Princess.

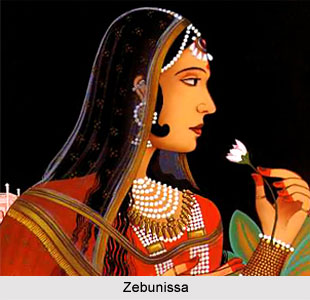

The very name the Prince chose indicates a special affection for this child, matching it with his own. `Zeb` means beauteous ornament- Aurangzeb means `Ornament of the Throne` and his daughter`s name means `Ornament of Womankind`. From her portraits, it can be seen that she was slim and tall, with a round face adorned with two moles on her left cheek. It was said that her skin rivalled the cascades of pearls that adorned her ear-lobes and neck. In fact it seems that her skin was not only fair but almost pale. No doubt she inherited this feature both from her father and from her noble Persian mother, who was reputed to have a delicate beauty. Zebunissa had lustrous hair, which shone with Sandalwood Oil, and her eyes were as black as her tresses. Zebunissa had naturally large, shapely eyes and did not need to outline them with antimony powder, or to thicken her long eyelashes with Mikhal or Kajal (made of soot from oil lamps), which was the contemporary fashion. Her lips were fine and she had small teeth. There was a fashion at the time for the women of the Mughal court to polish their teeth with a herb called Missi, which was like a black lacquer. However, Zebunissa`s teeth were naturally lovely and she never followed this unusual fashion. Homage was paid to the looks of this basically provincial young lady, a dedicated scholar and poetess who overnight was cast into the role of a leading beauty. When she granted audience from behind a silver trellis, supplicants would invariably begin by praising her reputed good looks.

However, despite her good looks the princess gave up dressing in a grand style rather early on and adopted the habit of wearing only black clothes. In the young Princess`s strange choice of colour for her dress, there may have been an element of astrology. On the other hand, her reason for deciding to wear black may have been because black gowns were supposed to be a sign of a person studying a vocation or searching for knowledge. In Islam, black is the colour of scholars and wise men. It is also the colour of the Abbasid caliphs. However she later discarded black when she imprisoned and took to wearing white only.

Religious influence on Zebunissa

Zebunissa`s religious experience followed a variegated path. She started by accepting some of her mother`s Shia practices in spite of herself, and then having Shahzadi Jahanara Begum Sahib`s, and also Dara Shikoh`s, somewhat unique Qadiria beliefs propagated to her. Subsequently she became interested in the Shattari Silsila for a time, but more so in an ardent disciple of this order, Aqil Khan. Finally, following the inclination of her father, she took up the Naqshbandia Order of Sufism, going to the extent of being initiated into the brotherhood like her aunt Raushanara.

Zebunissa, the patron of arts

The Princess was very well educated and was an avid reader with a quest for knowledge. She loved to read and write and has been constantly associated with her desk and inkwell.

The Princess was also quite well-versed in astrology and while still very young, she was capable of drawing her own horoscope. She became `very knowledgeable` in these sciences, according to her biographer Magan Lai. Zebunissa was a patron of poetry and the arts, and greatly encouraged this practice in her court. She was most interested in intellectual and edifying pursuits. The atmosphere at her personal court was pious, refined, and intellectual, as well as witty and enthusiastic. Verses would flow to and fro across the filigree screens separating the ladies from the men; there would be many impromptu gems of thought from the most brilliant contemporary literary minds of Delhi; there would be poetic jousts and much acclaim and appreciation all around. She conducted many poetry recitals in her Mahal, and became quite renowned for these gatherings. The sessions were attended by nobles, courtly ladies, men of letters, poets, and various intellectuals. There would be poetic tournaments in which guests would propose a subject, riddle, or question, to which the more learned guests would respond turn by turn, quoting verses or making a clever play on words or airing their wit on the chosen topic, which could be anything poetic or something that would impress the audience-cum-participants. There would be many beautiful couplets quoted, and intellectual jousts, often in verse, and these would be met by shouts of acclaim from the gathering. Zebunissa was known to excel in this play of retorts, quoting deftly or weaving an impromptu verse in appropriate reply to whatever was said. Poetic inspiration and sharpness of wit never failed her. A musician sometimes accompanied her, and often she would sing her verses. Her melodious voice was so moving that she brought tears to the eyes of her audience.

The princess`s standing as a patron of learning, literature, and poetry steadily grew. Mullah Mohammed Ardebil in honour of his benefactress gave her the flattering title of `Zaib al Tafari` (worthy of praise). One of her most ardent admirers was a poet called Waliullah. He idealized this distant poetess who already had become something of a mythical figure. He admired her and praised her beauty in his stylized poetry which was philosophical and, at the same time, full of imagery, of a mysticism inspired perhaps by Zebunissa herself. Her father was proud of her fame and encouraged her in her patronage.

Zebunissa the Poet

Zebunissa was a poet twice born, first of inspiration, then of pain. She assumed the pen-name of Makhfi (that which is concealed), representing her dark and Saturnine side. Slowly, the transformation of Princess Zebunissa into the poetess Makhfi began, in the bare halls of Salimgarh. Her poetry now reflected certain bitterness. Her poetry now spoke of the bitterness of her heart, her disappointments in love, regret at her own carelessness, and a deepening emotional resolution. Her poetic outbursts carried her towards more divine planes, far from the misleading emptiness of the world. Even before her incarceration, her poems had a deep emotional content often bordering on the profane. Her writing was never the dry, sophisticated, cerebral type. But she was always discreet to the extent of being mysterious, hence her pen-name, the Hidden One.

Imprisonment of Zebunissa

During her lifetime, the young girl was in the midst of machinations that were both political and spiritual, yet Zebunissa played out the numerous traps that arose with surprising maturity. However, she fell prey to a misunderstanding on part of her father later in life and was imprisoned by him in the fort of Salimgarh. Zebunissa was forty-three when she was incarcerated within the walls of Salimgarh. The glare of the blazing hot summer sun on the flat sand of this islet was so severe that it was known as Noorgarh, `noor` meaning light- `the fortress of light`. She turned deeply religious while in confinement and in isolation and anguish, she contemplated, and plumbed the depths of her heart till finally she confronted the infinity of the Creator. In her prison in Salimgarh she too wore only white, and no longer put on any jewellery apart from a necklace of tiny pearls. She abandoned the sumptuous black clothes which had been her emblem and with which she had started a fashion. In Salimgarh, Zebunissa`s poems developed the same tragic intensity. Perhaps, without Salimgarh, her poetry might never have gained the beauty and heights of passion which have passed down to posterity. In prison she learnt patience.

Zebunissa died in isolation, abandoned by her contemporaries, but posterity has accorded her a very prominent position in Persian literature, and she is remembered as a mysterious and romantic figure. Forty-five years after her death, in 1752, her works at last saw the light of day. Her scattered writings were compiled and published under the title of Diwan i Makhfi. It comprised 421 Ghazals and several quatrains. Hitherto, only the literati had heard of this obscure lady who was accounted a good poetess, even maybe come across an occasional verse by her. Once her complete works were brought out, people could appreciate the full depth and scope of this painful and passionate poetry, this dialogue of a soul with its creator. Her personal legend adds a dimension of drama and tragedy to the vast history of Persian and other related literature. Among the women of prominence during the Timurid dynasty, she forged her own characteristic and outstanding position.