About Indian Theatre History

The history of Indian theatre is the saga of changing tradition and an account of changing ritualism. Indian theatre is an effort of intensifying the social pattern in perhaps the most aesthetic way. Whether to reflect the very "unedited realities" of the society or to illustrate the divine edifying aspects of life, theatre in India definitely played a major role. The rich timeline of Indian theatre has therefore gone through a number of periods. These different periods were actually caused by the different rulers who invaded India time and time again.

The history of Indian theatre is the saga of changing tradition and an account of changing ritualism. Indian theatre is an effort of intensifying the social pattern in perhaps the most aesthetic way. Whether to reflect the very "unedited realities" of the society or to illustrate the divine edifying aspects of life, theatre in India definitely played a major role. The rich timeline of Indian theatre has therefore gone through a number of periods. These different periods were actually caused by the different rulers who invaded India time and time again.

Indian tradition ascribes a rather earlier date to dancing than to painting and sculpture. Historians believe that man must have learnt dancing much before and stepped into the "era of theatres". The history of Indian theatre is in fact the history of origin of the elements of drama which came together and weaved the rich fabric of Indian drama of which dance indeed formed the major part. Dance, the primeval unit of Indian theatre is portrayed in the prehistoric picture galleries, dotted throughout the country. Various enchanting dance formations depicted on rock surfaces points towards the fact that in the long gone days of the ancient times dance was the first `shrinkhala`(chain) as well as the "gulma" (cluster) of the Indian theatre which gradually evolved from the dance form. All the necessary ingredients of Indian theatre were present in primitive dancing hence the history of Indian theatre starts with dance. In those days the actor used masks, costumes, gestures, verbal sound to communicate and entertain and thus initiated the legacy of a dramatic art form, Indian theatre.

Over the centuries, the cave dwellers static civilisation has been still preserved amidst rich history of Indian theatre whilst giving a clue to the process of development of Indian theatre from its sheer rudimentary form.

The history of Indian theatre which started with the cave dwellers gained a rather realistic contour in the second century BC, with the introduction of the Sanskrit theatre. Realistically, Sanskrit theatre has been recognized as the very first representation of Indian theatre. Beginning in the long gone era of the second century BC, Sanskrit theatre was then the only medium of illustrating the religious and aristocratic Indian fervor. Theatre , as Bharata Muni says was then " the imitation of men and their doings (loka-vritti)" Natya Shastra seems to be the first attempt to develop the technique or rather art, of drama in a systematic manner. Sanskrit theatre remained to be a popular form of expression till the seventeenth Century. During the Eighteenth century, Sanskrit theatre slowly evolved as one of the eminent art form and was then popularly known as the "Indian Classical Dance Drama". Classical Indian theatre later witnessed a number of alterations to gain the modish shape. Based on the phases of the development of Indian theatre, the history of Indian theatre can actually be classified into three stages: Theatre in ancient India, Theatre in medieval India and the Modern Indian Theatre.

Theatre in ancient India of course played a major role in the over all enrichment of Indian tradition, culture, artistry and creativity since the remote past. The origin of theatre in ancient India has been marked as the result of the religious ritualism of the "Vedic Aryans". According to ancient Indian tradition Indian theatre was a life size art; practically nothing was left out of its scope. Theatre in ancient India was just not an artform but the systematic representation of " trividho shilpam nrutyam gitam vaditam cha" (dancing, singing an playing on musical instrument). Literature in Sanskrit started with the Vedic era and the rich history of Indian theatre holds the fact that Sanskrit plays were the first recognized representation of the Indian theatre. Illustrations of daily events, rituals, tradition, dance and music laced the Sanskrit plays while making the plays as one of the classical representation of applied art form in ancient India. Although indeed in a much crude manner the Sanskrit theatre did originate in India somewhat about 3500 years ago, yet its artistic glory never faded away with time.

Theatre in medieval India gradually became quite a thriving personification and of course a refined embodiment of the realities of life through dance, music and poise. During the middle ages the Indian subcontinent witnessed a number of invasions. And what came out as an immediate result is the grand fusion with the invaders from the Middle East and Central Asia, shaping Indian heritage and culture whilst offering it a whole new facet. . The over theatrical pattern of the ancient drama gained a rather rational rhythm in the style and pattern of theatres in the medieval India. The introduction of "Loknatya" during the mid 16th and late 16th century again added a whole fresh enunciation to Indian theatre during the medieval period.

The modern Indian theatre focused in portraying the change of the political set up in the country. The Indian theatrical culture was influenced by the British rule in India. During those 200 years of the British rule in the country, the Indian theatre came into the direct contact with the western theatre and this influence turned a new chapter in the history of Indian theatre while giving birth to the modern Indian theatre. It was the beginning of the nineteenth century when music, timber, song, dance, dialogue and emotion all were for the first time incorporated in the Indian theatre to offer it a modern facet. Not only in the acting pattern, changes were observed even in the designing of the theatre hall during this time. The theatres then incorporated huge orchestra pits and the seating arrangements were also then divided by metal bars. The overdramatic aspects were rationalized; gone are the days of witnessing the heroic deeds of the historical characters; modern Indian drama of the late 19th and early 20th century focused mainly towards a rather naturalistic and realistic presentation. Common man, daily life, social problem, health and economical problem were nicely manifested in modern theatres.

The rich chronicle of Indian theatre unveils the verity that theatre in India was always an important part of the rich Indian culture and tradition and is still the same. In the recent era Indian theatre has acquired that tinge of contemporary attribute in order to befit the modish requirement of the Indian society.

Contemporary Indian Theatre

Contemporary Indian theatre has evolved a great deal from the days of inception. Theatre has always been a mirror for man, and Indian theatre has not been any different. Indian drama is a reflection of a man`s world of the eternal conflicts that plague him, and through which he has experienced a range of emotions. Man has created a very complex language called theatre, a language that actually has the ability to redefine the natural concepts of time, space and movement. It uses a language that goes beyond the verbal, a movement that goes beyond the physical. Through this language of theatre he has been able to see himself for who he is, what he has made of himself and what he aspires to be. Thus it becomes extremely crucial to do the type of theatre which has a point to make and is also engaging enough. Only then is there the true synergy between the artist and the audience. This synergy is better described in our traditional theatre as Rasa.

Contemporary Indian theatre has evolved a great deal from the days of inception. Theatre has always been a mirror for man, and Indian theatre has not been any different. Indian drama is a reflection of a man`s world of the eternal conflicts that plague him, and through which he has experienced a range of emotions. Man has created a very complex language called theatre, a language that actually has the ability to redefine the natural concepts of time, space and movement. It uses a language that goes beyond the verbal, a movement that goes beyond the physical. Through this language of theatre he has been able to see himself for who he is, what he has made of himself and what he aspires to be. Thus it becomes extremely crucial to do the type of theatre which has a point to make and is also engaging enough. Only then is there the true synergy between the artist and the audience. This synergy is better described in our traditional theatre as Rasa.

In a pluralistic society like ours which is culturally so diverse, and a civilization that is as antique as the world, it is very hard to define what is quintessentially Indian. Theatre culture in various parts of the country specially the quality of plays, scripts and acting showcased in Bengali theatre, Kannada Theatre, Malayalam theatre and Tamil theatre are indeed one of the best in the country. Apart from them Marathi drama and theatre and Gujarati theatre have also contributed significantly towards the betterment of the theatre culture in India.

There are spaces that actually go beyond language and region, and they are the ones which are most useful. These are, as a matter of fact, more of ideological spaces and the whole purpose of making them is to come closer to the identity of India, its root and culture, rather than to create further hostile divisions. India as a nation has enough of such material. The three spaces in the context of Contemporary Indian Theatre can be described as the traditional, continual and radical respectively and none of these spaces are mutually exclusive.

There are spaces that actually go beyond language and region, and they are the ones which are most useful. These are, as a matter of fact, more of ideological spaces and the whole purpose of making them is to come closer to the identity of India, its root and culture, rather than to create further hostile divisions. India as a nation has enough of such material. The three spaces in the context of Contemporary Indian Theatre can be described as the traditional, continual and radical respectively and none of these spaces are mutually exclusive.

The traditional Indian theatre forms, with predominance in dance and songs, like Yakshagana, Swang, Nautanki and Tamasha have made a tremendous impact on the advancement of theatre in India. The word `Natya` is used for both Dance and Drama. In a Bharatnatyam concept, a varnam contains everything that theatre and dance all over the world strive for. It has grace and technique. It has power, it has emotions, dramatic tension, beauty, and most definitely it has style. A Rasika who has the capacity to enjoy this experience is truly a traditionalist in the best sense of the word.

It is absolutely vital to have tradition and continuity. The radical theatre of today is in all likelihood to become the traditional theatre of tomorrow. Some of the most powerful works in the field of Indian drama are from radicals like Rabindranath Tagore, Badal Sircar and Vijay Tendulkar. Tagore was among the first of the 20th Century dramatists to put the focus on the caste system and inequality through his plays.

One can have roots, and roots can grow into flowering trees. And on those trees are birds ready to spread their wings and fly. That is the completeness of life and its representative called theatre.

Indian Theatre After Independence

Theatre which was primarily used as the weapon against the British colonialism gained somewhat a modish dimension with the independence of India. The overemotional aspects and the theatrical exaggerations gained a rather modernized facet after the independence of India, Theatre which was always the major element in exhibiting the Indian art and culture became rather contemporary with the introduction of the modish theatrical style after India`s independence.

The urban theatre which emerged in independent India became a true representation of composition, textuality and polyglotism which ideally manifested that "unedited realities" of daily life in quite a stylized way. The representation of sanskrit plays and classical plays faded away and only remained in the memoirs of the timeline of Indian theatre. Drama in India after independence became lot more regional and structured. Theatre in India after independence had to face a situation in which tension prevailed and was therefore largely manifested. Tensions between the cultural past and the colonial past of India, between the western modes and thoughts and deep Indian tradition and indeed finally between the varied political visions were somewhat reflected in the Indian theatres after independence.

Indian theatre after independence gained a colossal maturity with the introduction of regional theatres. Bengali theatre, Hindi and Marathi theatre made their presence felt in quite a large way to manifest the social, political and economical condition of Independent India.

Indian theatre after independence gained a colossal maturity with the introduction of regional theatres. Bengali theatre, Hindi and Marathi theatre made their presence felt in quite a large way to manifest the social, political and economical condition of Independent India.

Bengali theatre which has its glorious history deep rooted with the British rule became somewhat a private entertainment process with the Independence of India. Bengali theatre played a major role in illustrating the likes and dislikes of the common people during the "British Raj"; and it is right after 1947 with the independence of India theatre in India especially in Bengal became the main element in evidencing the different political movement in a very coherent way. Theatre in India after independence was thus a logical way of expressing democratic ideas in the form of dance, music, dialogue and actions. In India, theater after independence was practiced in quite a large scale and can be actually divided into two large streams like urban theaters and rural theaters. The urban theater groups mainly focused on the political and social scenario of independent India however, the rural theatre groups did concentrate only on religious and historical plays.

Apart from these two broad categories folk theater also played a great role in elevating the rich cultural aspects of independent India. Folk theater further contributed in showcasing the age old tradition, ethnicity, religious fervor and ofcourse the rich heritage of sovereign India. It was to this shared heritage of rural folk theatre, in spite of its many linguistic and regional differences the theatre personalities in independent India defined its "Indianness". Folk Indian theatre after independence became thus the vehicle through which the distinctively Indian performance idiom might have developed.

A major change which came in Indian theatre after independence was with the formation of various theatre groups and companies. It was back in the year 1950s, Indian theater became a much professional art form. Theatre groups were formed during this time. Theatre groups started working with the great objective of theater development and also for promoting consciousness and awareness in regard to literacy, child abuse and usage of latrines etc.

However, in the timeline of Indian theatre the contemporary element was first noticed when social themes in plays made their presence felt and indeed with the introduction of the professional troupes in Indian theatre. Indian theatre after 1960s was totally managed by the professional troupes who actually started traveling throughout India in order to make theater to stand out amidst the crowd. Theater continued to be in its peak till the fag end of 1980s; and it is right after the introduction of "Street Theatre" during late 80s to the beginning of 1990s Indian theater broke the barriers of stage performance and approached the people directly.

Theatre in India during the late 90s and early 20s was just not the amalgamation of dance and music and of the altruists for entertainment but had a much deeper significance. Indian theatre after independence was an endeavor in reaching people of all strata and an effort to change the social and political ailments.

History of Modern Indian Theatre

History of modern Indian theatre depicts one of the productive phase in Indian theatre. Modernity of Indian theatre reached on the coattails of the British Raj in the mid-nineteenth century. As a result there were sweeping changes in theatre stages of India over the next hundred years, until 1947 and perhaps the subsequent decade, so that the only accurate adjectives for the following fifty years up till now can be post-modern, postcolonial or even contemporary. It is somewhat easy to determine the beginnings of modernism in Indian theatre, because the shift from pre-modern forms to modern ones here is so clearly distinguishable. Chronologically, too, it seems to nearly coincide with that turning point in Indian history, 1857, the First War of Indian Independence. However, modernism in theatres took some time to reach some theatre regions, as late as the mid-twentieth century - in alphabetical order, Dogri theatre, Kashmiri theatre, Konkani theatre, Maithili theatre, Manipuri theatre, Rajasthani theatre and Sindhi theatre.

History of modern Indian theatre depicts one of the productive phase in Indian theatre. Modernity of Indian theatre reached on the coattails of the British Raj in the mid-nineteenth century. As a result there were sweeping changes in theatre stages of India over the next hundred years, until 1947 and perhaps the subsequent decade, so that the only accurate adjectives for the following fifty years up till now can be post-modern, postcolonial or even contemporary. It is somewhat easy to determine the beginnings of modernism in Indian theatre, because the shift from pre-modern forms to modern ones here is so clearly distinguishable. Chronologically, too, it seems to nearly coincide with that turning point in Indian history, 1857, the First War of Indian Independence. However, modernism in theatres took some time to reach some theatre regions, as late as the mid-twentieth century - in alphabetical order, Dogri theatre, Kashmiri theatre, Konkani theatre, Maithili theatre, Manipuri theatre, Rajasthani theatre and Sindhi theatre.

But to rewind to the beginning, mere importation of the proscenium arch in itself did not herald modern Indian theatre, for the Playhouse (Kolkata, 1753) and Bombay Theatre (1776) catered exclusively to the small British populations in those harbour towns. Although the Russian bandleader Herasim Lebedeff opened his Bengali Theatre (Kolkata, 1795) with two Bengali productions, it proved a cul-de-sac that did not lead to a stage tradition either directly or indirectly. Since the British brought modern ideas to India, quite appropriately, the first `modern` Indian play was written in English by Reverend Krishna Mohan Banerjee in 1831 - The Persecuted, or Dramatic Scenes Illustrative of the Present State of Hindoo Society in Kolkata - though it was neither staged, nor did it inspire any successors.

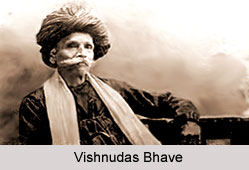

Another milestone on the road to modern theatre passed in 1853, when Vishnudas Bhave presented in Marathi language the first ticketed shows for native audiences at the Grant Road Theatre, Mumbai. Professionalism is not a key factor in the emergence of modern Indian theatre because many traditional troupes performed as professionals.

In Kolkata, the Bengali stage remained within the confines of private family theatres open only to invited audiences. But what the enlightened joint households of the Bengal Renaissance lacked by way of organized financial acumen, they amply compensated for by means of trailblazing drama. Some of them established competitions for original plays on socially relevant issues, which they then staged. This reformist zeal shaped frontline modernist theatre across the world.

In Kolkata, the Bengali stage remained within the confines of private family theatres open only to invited audiences. But what the enlightened joint households of the Bengal Renaissance lacked by way of organized financial acumen, they amply compensated for by means of trailblazing drama. Some of them established competitions for original plays on socially relevant issues, which they then staged. This reformist zeal shaped frontline modernist theatre across the world.

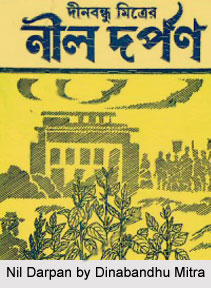

Consequently, by 1870 modernism was well under way, established thematically in eastern India and commercially in Mumbai. In 1872, the Kolkata stage also went professional, but in an absolutely unprecedented direction. From the inaugural production - Nil Darpan by Dinabandhu Mitra, about tyrannical indigo planters, was blatantly polemical and anti-British. Within four years the Bengali theatre outraged the colonial authorities so much that they passed the Dramatic Performances Act in 1876 to curb its subversive, seditious and provocatively patriotic tendencies. Like all the important elements of modernism, this legislation survives into post-modern times, virtually to the letter, as most state governments have not repealed it, ironically enough even invoking it to stifle their own opposition. In general, social and political plays comprise the core of meaningful Indian drama down to the present, definite legacies of modernism.

What has not lasted, however, is the mass appeal of theatre to Indians a hundred years ago. From the 1870s to 1930, theatre`s popularity touched its high-water mark in India, its place as favourite entertainment afterwards usurped by cinema and now perhaps by television. Modern Indian theatre in the West never attracted such a fervent following. In India, on the other hand, professional troupes rapidly evolved a formula combining melodrama with musical, which they used as a device to capture full houses and as an unlikely vehicle to express social or political messages when necessary.

Western Influence on Modern Indian Theatre

Western theatre narratives had a profound influence on modern Indian theatre. In the traditions of Euro-American, modernity is both a teleological principle of historical organization that separates the ancient and, medieval from the post-Renaissance world, and also a name for qualities that distinguish objects from one another within a given historical period. More specifically, literary modernity signifies a deliberate disengagement from past and present conventions in favour of verbal, formal, intellectual, and philosophical attributes that are new for their time, whatever the time. Horace, Dryden, George Eliot and Sylvia Plath are all moderns in this sense, as are the late seventeenth century proponents of libertinism in England, or the late twentieth century practitioners of minimalism in the United States.

However, in Indian literary history, the issue of modernity remains inseparable from that of the transformation of Indian cultural forms by Western influences under the inherently unequal conditions of colonial rule. The conventional historical argument is that Indian literary modernity was a consequence of the dissemination of the European literary canon on the subcontinent, the institutionalization of English literary studies in the mid-nineteenth century, the formation of modern print culture in the course of the nineteenth century, and the large-scale assimilation of modern Western literary forms novelistic and short fiction in the realist mode, historical drama, nationalist epic, romantic and confessional lyric, essay, discursive and critical prose, and biography and autobiography, among others. Concurrently, the influence of Western dramatic texts, conventions of representation, and forms of commercial organization displaced indigenous traditions of performance and established theatre as a modern, urban, commercial institution for the first time in the mid-nineteenth century. Given the ideological underpinnings of such a position, the `colonial` origin of Indian literary and cultural modernity has emerged as a key issue in the debates of the post-independence period, since colonialism is seen as destroying the very `essential` and `authentic` civilizational qualities that the orientalists had constructed in the nineteenth century. The resulting polemic, however, treats the culture of print very differently from that of performance.

Women in Modern Indian Theatre

Women in modern Indian theatre have been depicted in various shades. The question of gender has remained almost unaddressed in performance of modern Indian theatre. It has been seen that, in most of the studies done by scholars, works of modern theatre personalities attempts to destabilize regressive notions of tradition and to undo the sutures that have been put in place to hold together the idea of a composite Indian identity. In the recent years, people have become increasingly attentive to gender issues, interrogating the relationship of women to nationalism and modernity in the dramatic sphere, on the stage and in print culture, through thematic representations of women in theatre and through their contribution as actors, directors, and writers of plays.

Women in modern Indian theatre have been depicted in various shades. The question of gender has remained almost unaddressed in performance of modern Indian theatre. It has been seen that, in most of the studies done by scholars, works of modern theatre personalities attempts to destabilize regressive notions of tradition and to undo the sutures that have been put in place to hold together the idea of a composite Indian identity. In the recent years, people have become increasingly attentive to gender issues, interrogating the relationship of women to nationalism and modernity in the dramatic sphere, on the stage and in print culture, through thematic representations of women in theatre and through their contribution as actors, directors, and writers of plays.

Susan Seizer`s work on actresses of Special Drama in Tamil Nadu (2005), Minoti Chatterjee`s Theatre on the Threshold (2004), Deepti Priya Mehrotra`s Gulab Bai (2006) that details the story of a Nautanki dancer in the 1930s, and Rimli Bhattacharya`s discussion of the Bengali actress Binodini Dasi in My Story and My Life as an Actress (1998) elucidate how the images, roles, and lives of women as actors, performers, and participants involved complex negotiations with prevailing social ideologies and middle-class assumptions that emerged in response to the derisive discourses of colonialism. Additionally, Tutun Mukherjee`s Staging Resistance (2005), Lakshmi Subramanyam`s Muffled Voices (2002), and Betty Bernhard`s video recording of contemporary theatre activists (1998) represent a variety of positions and perspectives.

The nineteenth century nationalist themed Bengali theatre became complicit in the thematic erasure of women, despite the latter`s participation in anti-colonial agitations. Discussing the position of women in Marathi drama and theatre from 1843 to 1933, the recorded history of Marathi theatre show both marginalized and undervalued women`s real contribution to theatre.

In all India theatre movement, which is known as Indian People`s Theatre Association, IPTA, there was tremendous contribution on part of women and that actually helped in the success of the movement. There are also evidences that show that women, through the efforts of Anuradha Kapur, Tripurari Sharma, Maya Rao, and others in the 1970s and 1980s onwards took an active part in intensifying the street theatres, which kept the legacy of the IPTA alive.

In all India theatre movement, which is known as Indian People`s Theatre Association, IPTA, there was tremendous contribution on part of women and that actually helped in the success of the movement. There are also evidences that show that women, through the efforts of Anuradha Kapur, Tripurari Sharma, Maya Rao, and others in the 1970s and 1980s onwards took an active part in intensifying the street theatres, which kept the legacy of the IPTA alive.

The IPTA did play a crucial role in paving the way for women such as Shanta and Dina Gandhi (Pathak), Zohra Sahgal, and Sheila Bhatia, who played a significant role in the arena of performance by making culture a nationalist concern. Credit should also be given to these directors for taking up the many strands which had evolved through the post-Independence decades, the folk, the classical, Western high bourgeois, but also the feminist and the cinematic, to weave them together into a modernist idiom.