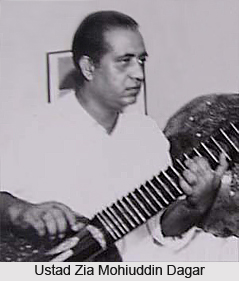

Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar can be called an enigma to the rest of the world, with such unfathomable qualities, that are still being discovered for the benefit of the listeners. Belonging to the erstwhile illustrious family of the Dagar gharana from dhrupadi music, he was the first person to break away from the tradition, only to learn rudra veena. And he was an ardent student, who stood against all odds to pursue in this course, and he was again the man behind reviving the instrument`s waning splendour. Through him, rudra veena had a fresh impetus to drive forward. Accordingly, his fame and latent talent came to public view, which lamentably, survives no more. Most of his live performances have not been recorded, and the present audience is missing much of this man. He though has left behind him a constellation of performers to carry on in his line of legacy.

Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar can be called an enigma to the rest of the world, with such unfathomable qualities, that are still being discovered for the benefit of the listeners. Belonging to the erstwhile illustrious family of the Dagar gharana from dhrupadi music, he was the first person to break away from the tradition, only to learn rudra veena. And he was an ardent student, who stood against all odds to pursue in this course, and he was again the man behind reviving the instrument`s waning splendour. Through him, rudra veena had a fresh impetus to drive forward. Accordingly, his fame and latent talent came to public view, which lamentably, survives no more. Most of his live performances have not been recorded, and the present audience is missing much of this man. He though has left behind him a constellation of performers to carry on in his line of legacy.

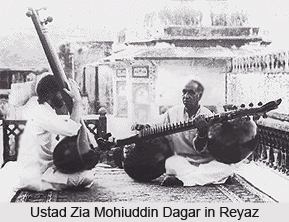

Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar Magic with Rudra Veena

Few in post-Independence India could evoke the astuteness of dhrupad on the rudra veena as Ustad Z.M. Dagar. He was the son of Ustad Ziauddin Dagar, a court musician attached to the Udaipur court. The Dagar family and its 19 unbroken generations of dhrupad singers and rudra vainiks are something worth in documented history. He grew up in the ambience of the Udaipur court listening to his father play the divine rudra veena. Soon he decided to break with family tradition and become a vainik instead of a dhrupad singer. With the best of intentions, his father introduced him to the profound and subtle aspects of playing this difficult instrument.

The rudra veena, like dhrupad, was its lowest ebb during the years following the re-organisation of princely states in 1948. Following this historical event, the princely states could no longer afford to support the entourage of highly endangered dhrupad musicians who wholly depended on royal patronage. In the years that followed Independence, the Dagars were compelled to look towards the new and rising class of audiences, as also the state for support and patronage. This was no mean task, given that the audiences largely preferred khayal, and instruments like sitar and sarod, over the Dagars` more hoary and dignified offerings.

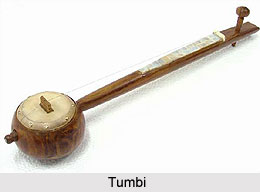

Yet Khansahib persisted in learning and perfecting his technique under his family members, against great odds like poor monetary benefits and lack of audience. Importantly, he realized that he ought to make modifications to the instrument to take on the profound tonalities of dhrupad, something until now un-attempted. After extensive research and study, he modified the instrument by adding a carved peacock sound chamber at one end and a dragon`s head at the other. He then made the two tumbas (resonators) on either end larger, in order to enhance the deeper tonalities of the instruments. The frets were rearranged for greater flexibility and he also used heavier gauge strings for bass-effects. He also departed from the traditional mode of sitting on the vajrasana posture and holding the veena vertically on the shoulder. Instead, he sat cross-legged and held the rudra veena nearly horizontally in the way the Saraswati veena is held in the South India tradition.

Yet Khansahib persisted in learning and perfecting his technique under his family members, against great odds like poor monetary benefits and lack of audience. Importantly, he realized that he ought to make modifications to the instrument to take on the profound tonalities of dhrupad, something until now un-attempted. After extensive research and study, he modified the instrument by adding a carved peacock sound chamber at one end and a dragon`s head at the other. He then made the two tumbas (resonators) on either end larger, in order to enhance the deeper tonalities of the instruments. The frets were rearranged for greater flexibility and he also used heavier gauge strings for bass-effects. He also departed from the traditional mode of sitting on the vajrasana posture and holding the veena vertically on the shoulder. Instead, he sat cross-legged and held the rudra veena nearly horizontally in the way the Saraswati veena is held in the South India tradition.

Life In Music for Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar

Khansahib`s immense eruditeness and his power of genius are reflected in his deeply pondered renditions. His alaaps are awesome, majestic, spacious and, when in the best of moods, sublime. They have the power to chastise the mind, because they come as a sequence of pure notes. The deep-toned rudra veena he designed amplifies his innate sense of gravity. His resonant meends dart like tonal arrows from the taut bow of the rudra veena. Even the most delicate emotional shades and hues of the raaga become enchantingly severe and monumental in his hands. The lingering echoes stay on in the mind like after-tremours long after the music is no more. Those who want to experience the aura of the austere, the enigmatic and the deeply searching in dhrupad, must listen to Khansahib`s alaaps absorbedly, because they are not so much prototypes of musical virtuosity, as they are aesthetic and spiritual revelations cast in the ethereal curves of sound. For it is in his hands and through his ethereal instrument that the music of the earth comes close to at least faintly replicating the unfathomable music of the spheres.

Unfortunately, not many music companies in the country have made recordings of this great artist. Yet, of the few available, his Ahir Bhairav and Malkauns brought out by Swarashree, and the All India Radio recording of his Chandrakauns brought by HMV, give the listener a fair idea of the hauntingly meditative tone of his instrument as also of his disciplined approach to these raagas. The astounding meends, fast gamaks and the pounding rhythmic movements in the dhrupad section make them a treat to listen to. The live recordings made at the University of Washington of his Marwa and Bageshri (alaap and jod only), brought out by the American company Raga, display many of the profound characteristics of his approach in detail. However, one of his exceptional recordings is his lengthy Yaman, brought op by Nimbus, recorded just prior to his death in 1990. The alaap-jod-jhala section is, to say the bare minimum, pure gold. The oceanic depth of Yaman becomes more decipherable as Khansahib dives into those depths where few have dared and surfaces with treasures perceived by the human eyes. One only wishes that more recording companies would bring out his live recordings for the benefit of listeners, because it is this music that the world must relish.

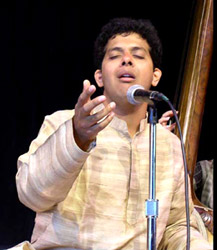

Towards the last decade of his life, Khan Sahib or Bade Ustad as he was called by his students, along with his brother Ustad Zia Fariduddin Dagar taught at the Dhrupad Kendra in Bhopal. The Gundeccha bandhu were two of the finest students to come forward from this intensive training. Khansahib also trained his competent son Bahauddin Dagar in the instrument. Chandrashekar Naringekar and Pushparaj Khoshti learnt the surbahar under him