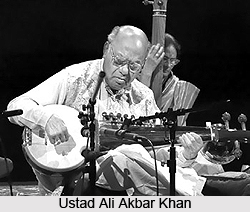

Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (14 April 1922 - 18 June 2009) was trained under his disciplinarian father, Ustad Allauddin Khan. He fled to Mumbai to try his luck in AIR Bombay, but was traced back home by his father. Few years later, he started showcasing his hidden talent, becoming the court musician of the King of Maihar. But, his first true achievement came when he was announced the court musician of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. His mastering the sarod and its every nuance wondrously complemented his jugalbandis along with Pt. Ravi Shankar, regarded the high-point of his billowing career. His Raaga renditions like Bilaskhani Todi, Palas Kafi, Shree or Manj Khammaj are etched in the minds of everybody who were privileged enough to have heard it. His style of carrying the vilambit gats evokes a sense of sculptured beauty, plenty of them captured in recorded versions through umpteen albums.

Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (14 April 1922 - 18 June 2009) was trained under his disciplinarian father, Ustad Allauddin Khan. He fled to Mumbai to try his luck in AIR Bombay, but was traced back home by his father. Few years later, he started showcasing his hidden talent, becoming the court musician of the King of Maihar. But, his first true achievement came when he was announced the court musician of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. His mastering the sarod and its every nuance wondrously complemented his jugalbandis along with Pt. Ravi Shankar, regarded the high-point of his billowing career. His Raaga renditions like Bilaskhani Todi, Palas Kafi, Shree or Manj Khammaj are etched in the minds of everybody who were privileged enough to have heard it. His style of carrying the vilambit gats evokes a sense of sculptured beauty, plenty of them captured in recorded versions through umpteen albums.

At the age of 13 he gave his debut performance at a music conference in Allahabad in 1936. He did for the sarod, what Ravi Shankar did for the sitar. Initially he was taught dhrupad and dhammar first and the sarod from the age of nine.

Ali Akbar too, along with his father, joined Uday Shankar`s ballet troupe and toured many countries in the West. Soon enough, Ravi Shankar became his guru-bhai and later his brother-in-law. In the mid 1950s he started visiting the United States for long spells. After a while, sensing lucrative prospects there, he settled down in San Rafael, California and started a school of music there. During the 1960s and 1970s, both Ali Akbar and Ravi Shankar gave a number of jugalbandis at various places in the U.S., and in European countries. This partnership proved to be extremely fruitful while it lasted. The concept of jugalbandi received solidity and weight in the hands of these nearly matched instrumentalists, who shared similar ideas on music and could take it to new heights. Some of these jugalbandis were commercially recorded, especially their Hem Bihag, Sindhu Bhairavi, Bilaskhani Todi, Palas Kafi, Shree and Manj Khammaj. These recordings are truly great contributions to Indian music.

Though a lot less flamboyant, he made innumerable innovations to the instrument and the style of playing in a much quieter manner. His own innovative addition gives his alaaps the meticulous structure, the grand spaciousness and solemn depth, typical of dhrupad. One notices the predominance of the tantkari-ang in his alaaps. Ali Akbar does not hesitate to judiciously coalesce in the gayaki-ang into his alaaps and gats when required. His jods and jhalas, while neither glitzy nor mechanical, display much spontaneity and melodic variety. His command over rhythm is superb. Ali Akbar is a widely recorded artist.

During the 1970s, following his explosive success in the west, Ali Akbar also went on to create a handful of raagas like Chandranandan, Medhavi, Lajwanti and Gauri Manjari. Of these, Chandranandan seems quiet popular among his students.

Ali Akbar Khan married thrice and is survived by seven sons and four daughters. He was awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 1989. In 1991 he received a MacArthur Fellowship. He received the National Endowment for the Arts` prestigious National Heritage Fellowship, the United States` highest honour in the traditional arts in 1997.