Turtle is a reptile of the order Testudines. About two hundred and twenty species of turtles exist today. They inhabit land, sea, rivers and bodies of fresh and brackish water in tropical and temperate regions. The Leatherback sea-turtle, largest of the living turtles, has also been reported from arctic waters. The term `turtle` in this account applies to any member - tortoises and terrapins included - of the order Testudines, one of the class Reptilia. The earliest true turtles which, unlike modern forms, possessed teeth in their palates are known from the Triassic (about two hundred million years ago). Of about twenty two families then, twelve survive today. These are usually classified into two suborders - the more primitive Pleurodira, consisting of two families unrepresented in the Indian subcontinent, the members of which retract the head and neck sideways; and the Cryptodira, which do so in a vertical plane.

Turtle is a reptile of the order Testudines. About two hundred and twenty species of turtles exist today. They inhabit land, sea, rivers and bodies of fresh and brackish water in tropical and temperate regions. The Leatherback sea-turtle, largest of the living turtles, has also been reported from arctic waters. The term `turtle` in this account applies to any member - tortoises and terrapins included - of the order Testudines, one of the class Reptilia. The earliest true turtles which, unlike modern forms, possessed teeth in their palates are known from the Triassic (about two hundred million years ago). Of about twenty two families then, twelve survive today. These are usually classified into two suborders - the more primitive Pleurodira, consisting of two families unrepresented in the Indian subcontinent, the members of which retract the head and neck sideways; and the Cryptodira, which do so in a vertical plane.

Six of the ten Cryptodire families are represented in the Indian region, here meaning the land and ocean south of the Himalaya, and extending westwards to Pakistan and eastwards to Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and Sumatra. They are the Emydidae, loosely, the freshwater turtles; the Testudinidae, mainly land tortoises; the Platysternidae which has a lone species, the big-headed turtle; the Cheloniidae and Dermochelidae, both sea-turtle families; and the Trionychidae or soft-shelled turtles. Except for the last two families, in which leathery skin overlies the bones of the carapace (upper shell) and plastron (lower shell), turtles possess bony shells covered by horny shields or laminae. Typically, the larger of these shields number thirteen on the carapace and twelve (six pairs) on the plastron. Those on the carapace are arranged in three rows: five vertebral shields along the midline, and rows of four coastal shields on either side. Smaller shields called margins, often numbering twelve on each side, usually with an anteriorly placed nuchal shield, occur on the outer border, surrounding the vertebrals and coastals. Carapace and plastron are often joined by a `bridge` athwart the middle, leaving openings at the front for the head and forelegs and at the back for the hindlegs and tail. Most turtles can withdraw their head and limbs into the shell for protection, the exception being sea-turtles, which therefore occasionally lose limbs to predatory sharks.

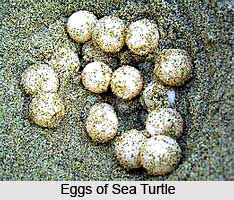

Turtles have lungs and breathe air, but some aquatic species that have additional vascular organs near the throat and vent will also utilize dissolved oxygen directly from the water. Most turtles can remain for a long time without breathing, but even the most aquatic, the sea turtles, can drown, as frequently happens when they are caught in trawl nets at sea. All turtles are oviparous and lay eggs that are hatched by the sun`s heat. Most species excavate a chamber in sand or mud to receive their eggs, others merely select a suitable crevice for this purpose. The body temperature of turtles, and therefore the level of activity, is largely determined by the ambient temperature. Hibernation in cold weather under mud and, in some sea turtles, on the bed of the sea, occurs. Soft-shelled turtles estivate under mud as their aquatic habitat dries up, and are set free with the onset of the monsoon.

Turtles have lungs and breathe air, but some aquatic species that have additional vascular organs near the throat and vent will also utilize dissolved oxygen directly from the water. Most turtles can remain for a long time without breathing, but even the most aquatic, the sea turtles, can drown, as frequently happens when they are caught in trawl nets at sea. All turtles are oviparous and lay eggs that are hatched by the sun`s heat. Most species excavate a chamber in sand or mud to receive their eggs, others merely select a suitable crevice for this purpose. The body temperature of turtles, and therefore the level of activity, is largely determined by the ambient temperature. Hibernation in cold weather under mud and, in some sea turtles, on the bed of the sea, occurs. Soft-shelled turtles estivate under mud as their aquatic habitat dries up, and are set free with the onset of the monsoon.

Sex dimorphism may manifest itself as a concavity in the plastron of the male; size disparity between the sexes, the female often being the larger; a greater length and thickness in the tail of the mail, with the opening of the vent being farther back than in the female. The age of some turtles, especially land tortoises, can be reckoned by counting the annual growth of rings on individual shields. This method fails after the early years of its life, as the rings lose their definition. About fifty five kinds of turtles of forty six species representing twenty five genera are found in the Indian region.

Half of India`s turtle species are Emydids, distinguishable from the tortoises (family Testudinidae) by their more or less flattened limbs and wedded digits, as opposed to the relatively cylindrical limbs and separated digits of the tortoises. Six species of the genus, Melanochelys occur in India. The commonest is M.trijuga, the Hardshelled terrapin, which has six races itself. At nightfall, particularly in wet weather and surroundings, these turtles often leave the ponds or tanks which are their usual habitat by day, in order to forage on land. Plant matter is the food preferred. If handled when freshly caught, M.trijuga may produce a disagreeable-smelling scent-gland secretion; the odour may also serve as a sexual attractant - both males and females possess the glands. Turtles have a well-developed sense of smell.

In the genus Cyclemys, the rear margin of the shell has tooth-like projections (serrations). Two species, C.mouhoti and C.dentata, are found in India. Both have an indistinct hinge across the undershell, thus enabling them to move the forepart of the plastron rather like a trapdoor.

Cuora amboinensis, the Malayan box turtle, which is common in ponds and swampy areas in south-east Asia, was first recorded in India as lately as 1979, at Great Nicobar and Trinkat islands. A well-defined hinge separates its undershell into two movable lobes which can `box up` the turtle protectively. On being handled, the timid animal may squirt from its vent a fluid (not urine) from its anal sacs, which are accessory organs of respiration.

The two eggs laid by a twenty one centimetres long individual at Trinkat island were typical of the eggs of the Emydidae: ellipsoidal, white and brittle; one measured 51X29 millimetres. In all other turtle families found in India, the eggs are almost spherical. Sea turtles lay soft, thin-shelled, parchment-textured eggs. Some Emydids lay over thirty eggs per clutch. Six species of the genus Kachuga occur in the Indian areas. They inhabit the rivers of the northern and eastern India, are predominantly herbivorous and are much relished as food, except for k.tecta tentoria, one of the two races of the conical-shelled Tent or Dura turtle; its flesh is reportedly mildly poisonous if eaten. The more colourful species of kachuga, being popular abroad as pets, were among those that were exported from India or Europe, the U.K. and the U.S.A. until the recent enactment of protective legislation.

K.Kachuga lays its eggs in sand on the banks of the Ganga River. The males apparently develop a red coloration on the top of the head, perhaps seasonally. Batagur baska, an estuarine turtle whose shell reaches five hundred and ninty millimetres in length, is probably the largest of the Emydidae. During the last century it was reported to abound at the mouth of the Hooghly River and that large numbers were brought to Kolkata for sale and consumption. The male in certain seasons assumes striking colours. At five hundred millimetres in shell length, the female of the riverine species Hardella thurgi, or Thurg`s batagur, reportedly grows to a length almost three times that of the male. The turtle`s flesh is esteemed in Bengal. The carnivorous Geoclemys hamiltoni is elegantly spotted with yellow on its dark shell and soft parts. Its fully webbed digits proclaim the turtle`s aquatic disposition.