Introduction

Harmonium is most widely known and used free-reed aero-phone in India, though the eminent ones are also the mouth-organ and the accordion. There are indeed various types of harmonium and mostly they have been imported from the West and the harmonium was perhaps introduced into this country in the late nineteenth or the early twentieth century. The uses of harmonium find a place in the music of all kinds - folk, light, dramatic and even the highbrow.

Harmonium is most widely known and used free-reed aero-phone in India, though the eminent ones are also the mouth-organ and the accordion. There are indeed various types of harmonium and mostly they have been imported from the West and the harmonium was perhaps introduced into this country in the late nineteenth or the early twentieth century. The uses of harmonium find a place in the music of all kinds - folk, light, dramatic and even the highbrow.

Origin of Harmonium

Origin of Harmonium mainly dates back to the western culture. The first harmonium was invented in Paris in the year 1840 by Alexandre Debain. These instruments generally weigh less than the similarly sized pianos. An added pull of the harmonium in tropical regions is that, unlike the piano, this instrument holds its tune regardless of humidity and heat. Reed organs which are folded up into container the size of a very large suitcase or small sized trucks were made for missionaries, travelling evangelists, and road musicians. These harmoniums actually had a short sized keyboard and very few stops, but they were more than sufficient for keeping singers more-or-less on pitch.

Origin of Harmonium mainly dates back to the western culture. The first harmonium was invented in Paris in the year 1840 by Alexandre Debain. These instruments generally weigh less than the similarly sized pianos. An added pull of the harmonium in tropical regions is that, unlike the piano, this instrument holds its tune regardless of humidity and heat. Reed organs which are folded up into container the size of a very large suitcase or small sized trucks were made for missionaries, travelling evangelists, and road musicians. These harmoniums actually had a short sized keyboard and very few stops, but they were more than sufficient for keeping singers more-or-less on pitch.

Indian music is mainly based on melody, rather than harmony that has also made two handed playing unnecessary and Indian musicians are also used to sitting cross legged on the ground to play, rather than on chair. So the sub-structure of the harmonium is removed and also the bellows moved to the back side of the instrument where they are basically operated with one hand while the other hand plays the keyboard. Dwarkanath Ghose of Calcutta (now Kolkata) personalized the imported harmony flute and urbanized the hand held harmonium that has subsequently become a vital part of the Indian musical scenario today.

A well-liked and well accepted function and usage of harmoniums is by followers of a range of Hindu and Sikh faiths, who use it in the devotional singing of prayers, called bhajan or kirtan dance. There will be at least one harmonium in any Mandir (Hindu temple) or Gurdwara (Sikh temple) around the world. The harmonium is also commonly accompanied by the tabla as well as a dholak. To Sikhs, the harmonium is known as the vaja or baja. It is also referred to as a "Peti", a loose reference to a "box", in some parts of North India and Maharashtra.

History of Harmonium

History of Harmonium goes back a long way. With the current state of knowledge, any attempt to specify when, how and in which form the harmonium became established in India is futile. Literature states anything between the ends of the 18th century - which is, in reality, impossible, since the harmonium was only patented in the middle of the 19th century, and the middle of the 19th century. There are too few sources to enable a complete chronological documentation on the history of the harmonium in India.

History of Harmonium goes back a long way. With the current state of knowledge, any attempt to specify when, how and in which form the harmonium became established in India is futile. Literature states anything between the ends of the 18th century - which is, in reality, impossible, since the harmonium was only patented in the middle of the 19th century, and the middle of the 19th century. There are too few sources to enable a complete chronological documentation on the history of the harmonium in India.

The first known mention of the harmonium in Indian literature dates back from 1868. Assuming the import of a fully developed European harmonium, the earliest possible date could be the early 1840s, since Alexandre Debain patented his (pressure system) harmonium in 1842, and none of the many parallel developments could have been exported much earlier. The idea of an indigenous Indian development can be abandoned: although the free reed principle is a South-East.

Asian development and its manufacture in Europe a reaction to knowledge of the corresponding instruments, this type of reed played no veritable role in India at the time. What seems to be another "novelty" for Indian instrument manufacture - the keyboard - is a different case. Independently from the not yet entirely explored use of keyed instruments, they had a certain representative function as diplomatic gifts. In 1579, an organ was presented at the court of Akbar in Fatehpur Sikri, and organ music played a certain role at the Mughal`s court during the following decades. These European instruments, becoming highly symbolical objects of prestige, initially had a neutral function of cultural ambassadorship, starting with the onset of European presence in India.

A close relationship between musical instrument and cultural identity is evident in the situation the first British settlers were faced with in the Indian colonies: they were a small minority of great affluence, only starting to appreciate the cultural past and present of India. This situation fostered an environment that even much later, in the mid-19th century, was favourable not only for the harmonium, but for all types of European instruments.

As an alternative to the piano, the harpsichord and other common European instruments suitable for soloist domestic performance, the harmonium offered a decisive advantage: stringed instruments certainly were problematic export goods, since the fragile and tightly fitting woodwork showed little tolerance for the abrupt change of climate and high humidity. In addition, termites posed a real threat to wooden piano frames at that time, as piano builders` attempts to create instruments suitable for the tropics had not yet yielded any satisfying results. Nevertheless, the pianoforte remained a status symbol with a function within the British households that was not to be relinquished easily. Still, instruments with free reeds could be used as substitutes, being more robust and therefore offering a long-term alternative to the piano, also for musical purposes. And even if the abrupt change of climate had an effect on the harmonium`s tuning, it was much less severe than with the piano.

In academic literature, the possibility that the harmonium`s introduction to India could have been outside the context of Christian proselytisation is hardly considered. The harmonium gained a firm foothold early on and in many missionary stations - for want of a church organ the harmonium presented an alternative for several reasons: its tuning was robust, it was comparatively easy to transport, and no calcants were required - for all these reasons it was most suitable for Christian music. But from a historical viewpoint, one cannot assume that the missionaries brought along harmoniums from the start: the missionaries were sent out before the harmonium was developed, which means that the instrument`s establishment must have been brought about by some directive from the mission headquarters. This could not be substantiated yet. Independently from that, it is also possible that diverse keyed instruments (e.g. portative organs) were assumed to be harmoniums at a later stage, which may have contributed to the association of the harmonium with Christian missions.

What can be verified is the import of many instruments for a different purpose, namely for domestic performance in the European households in India (as mentioned earlier), especially in Calcutta (Kolkata). Jotindra Mohan Tagore (born 1831) is said to have imported the first musical boxes and barrel organs, but it most likely means that he was the first Indian to import these instruments.

By the 1880s, the import figures for harmoniums had increased impressively - initially the instruments were imported from Britain, later also from the USA. The main reason for rise of a local harmonium manufacture was probably that the bulky pedal Harmonium manufactured by Alexandre and other French makers were expensive and unsuitable for the average Indian homes. Nonetheless, the occasional import of European musical instruments that had begun some decades earlier developed into an independent branch of trade, which no longer (as opposed to the apparent situation before that) was firmly in British hands, but offered British, Anglo-Indians (Indians with Anglophone education) and Indians an opportunity to do business to an equal extent.

What is meant is firstly the families of the British Raj, i. e. European households of the upper social class, but also (especially as far as the Kolkata firms are concerned) members of the Brahmo Samaj, the reformist-religious society situated in Bengal whose progressive members mainly cultivated European thought and culture. The Brahmo Samaj used the harmonium to accompany songs at religious meetings and to perform Western music privately.

The history and formation of the Bengal middle class (as it is often called and to which the Brahmo Samaj belongs) is a phenomenon of social history that has been described often, and this group can be seen is a second link between British and Indian circles, along with the missionaries. The Brahmo Samaj seems to be one of the first institution-like Indian circles that adopted the harmonium This correlates with the fundamentally progressive attitude of the society, an attitude also extremely open towards the West, and which was accompanied by the patronage of indigenous musical traditions and the cultivation of Sanskrit literature and poetry as well as the study of traditional local music and European concert music with equal open-mindedness, not only in the Samaj households.

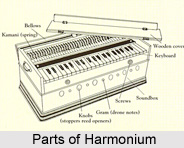

Construction of Harmonium

Construction of harmoniums is actually a process that leads to the making of this popular instrument. This instrument, harmonium, consists of banks of brass reeds (metal tongues that vibrate when air flows over them), a pumping apparatus, stops for drones (some models feature a stop that causes a form of vibrato), and a keyboard. The timbre of the harmonium, despite all its similarities to the accordions is actually made in a critically different way. Instead of the bellows causing a direct flow of the air over the reeds, an external feeder bellows then inflates an internal reservoir bellows inside the harmonium from which air escapes to vibrate the reeds. The design is very similar to bagpipers, as it allows the harmonium to also create a continuously sustained sound. (Some better-class harmoniums of the 19th and early 20th centuries incorporated an "expression stop" that bypassed the reservoir, allowing a skilled player to regulate the strength of the air flow directly from the pedal-operated bellows and so to achieve a certain amount of direct control over dynamics.)

Construction of harmoniums is actually a process that leads to the making of this popular instrument. This instrument, harmonium, consists of banks of brass reeds (metal tongues that vibrate when air flows over them), a pumping apparatus, stops for drones (some models feature a stop that causes a form of vibrato), and a keyboard. The timbre of the harmonium, despite all its similarities to the accordions is actually made in a critically different way. Instead of the bellows causing a direct flow of the air over the reeds, an external feeder bellows then inflates an internal reservoir bellows inside the harmonium from which air escapes to vibrate the reeds. The design is very similar to bagpipers, as it allows the harmonium to also create a continuously sustained sound. (Some better-class harmoniums of the 19th and early 20th centuries incorporated an "expression stop" that bypassed the reservoir, allowing a skilled player to regulate the strength of the air flow directly from the pedal-operated bellows and so to achieve a certain amount of direct control over dynamics.)

If a given harmonium has two particular sets of reeds, it is possible that a second set of reeds can also be activated by a stop that means each key pressed will play two reeds. Professional harmoniums feature a third set of reeds, either tuned with an octave higher or in unison to the middle reed. This actually makes the sound fuller. In addition to that, many harmoniums also feature an octave coupler, a mechanical linkage that opens a valve for a note an octave below or above the note being played, and a scale changing mechanism, which allows one to play in many keys while fingering the key of one scale.

Harmonium is a type of instrument that is made with one, two, and three or, occasionally, six sets of reeds. Classical instrumentalists usually use one-reed harmoniums, while a musician who plays for a qawwali (Islamic devotional singing) usually uses a three-reed harmonium.

By playing the harmonium, the human voice becomes artificial, because according to the tradition of Indian classical music, the real notes of 22 shruties should be produced. There are certain notes in classical music which cannot be reproduced by the harmonium, for example _G_ in raga tod, M in raga Lalit, etc. Therefore, practice of svaras on the harmonium tends to make the swaras unnatural or unreal. Many classical singers frown at the use of harmonium.

It is not good to practise svara-sadhana (note modulation) on the harmonium. It is better to practise the svaras on the tambura. When the strings are touched, they vibrate and the note continues to sound for a while, but in the case of the harmonium, the tone starts for a while, but in the case of the harmonium, the tone starts with inflation of the bellows and when the bellows stop, the note comes to an end.

Meend (glide from one note to another) and gamak (delicately mixing svaras in a raga) are not possible on a harmonium and as such, richness and excellence of melody is unavailable. This instrument is not good for accompaniment of vocal music, because it cannot reproduce the various delicate shades of vocal music. It is better to use a sarangi or bela (a kind of violin) for the accompaniment of vocal music.

Tuning of Harmonium

Types of Harmoniums are varied. Harmoniums are reed instruments played by pumping air through a bellows. The quality of the sound of each instrument is mainly affected by the quality of the wood used, the number of reed banks, and the adeptness of the artist in his or her playing skills.

Types of Harmoniums are varied. Harmoniums are reed instruments played by pumping air through a bellows. The quality of the sound of each instrument is mainly affected by the quality of the wood used, the number of reed banks, and the adeptness of the artist in his or her playing skills.

When selecting a harmonium, it is wise to consider which feature actually is needed and one can make the selection accordingly. Some features sound nice, but in actual use, you might not ever need or use them. Harmoniums are classified by their features. The main features are:

1. Standard harmonium is the basic form of the harmonium which is used by most people in case of artists, performers and for home usage as well.

2. Portable harmonium is a standard harmonium that settles into a cavity and closes to form a suitcase shape.

3. Scale changer is also a simple harmonium with the difference that the keys are not fixed over the reed board. The keys are instead mounted on a movable plate which slides sideways making one key place able on another note.

4. Hand and foot harmoniums have bellows at foot level with the main body at a higher level and connected to the bellows with pipes.

Construction Quality in Harmoniums

Construction Quality in Harmoniums

The quality of the wood affects the resulting sound. Some of the priciest harmoniums are constructed with hard woods, such as teak or mahogany, which give them a very resonant sound. However, it makes them very heavy to carry around. Harmoniums made from lighter woods, such as pine or fir, are easier to carry, so this should be a consideration while choosing an instrument. If travelling along with the harmonium is the plan, then probably a lighter model can be a good choice.

Standard or Fold-Up in Harmoniums

Standard harmonium models usually have two handles on their sides. They are the classical model and probably most common world-wide.

Some harmoniums fold up, which is a feature that makes the instrument easier to transport. There are two basic types of folding models, one type folds up into itself and the bellows board covers the top. An example is made by the Bina brand. These are a bit tricky to fold and unfold, but once the user gets used to it then travelling along with the same could be a good option.

The other style folds into itself and a separate lid cover the whole instrument. It is called a suitcase model. These are much easier to fold and unfold, and the detachable cover can be used as a stand to raise the instrument to a better playing height. However, they are usually much pricier as they are most often found on harmoniums that are constructed out of heavier wood. And even though they are easier to fold up, they are heavier to carry.

Number and Type of Reed Banks in Harmonium

The sound of the harmonium is affected by the number of reed banks it has. There are harmoniums with 1, 2, 3, or 4 banks of reeds. Usually each bank has a different sounding set of reeds, most commonly called male, female, bass or tenor. Most often, different reeds are placed in each of the reed banks and the mix of sound from them helps create each harmonium`s unique sound.

A greater number of reed banks contribute to the complexity of the overall sound, but more reed banks also means a heavier instrument. More reed banks usually means a wider reach when playing a harmonium. Two or even three-reed bank harmoniums usually have an acceptable reach.

Scale Changer in Harmoniums

Some harmoniums have what is called a key changer, or scale changer. This is a complex mechanism that allows shifting the keyboard to the left or the right. This is a feature that most harmonium players will never use.

Coupler in a Harmonium

Some harmoniums have a coupler, a device that connects one key with its higher or lower corresponding key. When the coupler is engaged, it will play two octaves of the same note at the same time. This has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that it can make a harmonium that has a lesser number of reed banks sound like it has more, usually giving a richer sound. The disadvantage is that user will need to pump more air into the instrument to maintain the sound, so one needs to work harder on pumping.

Bellows in Harmoniums

Air is pumped into the harmonium with the bellows. There are actually two sets of bellows, one that can be seen and one that is internal. The external bellows can have 1, 3, 5, or 7 folds.

Bellows can open to the side or the top, and which type the users have depends on the preference. Many, but not all, of the top opening bellows have tighter bellows springs and require a bit more muscle to pump, but ensure that the internal bellows has lots of air. Many side-pumping bellows have a softer pumping action and can also ensure plenty of air for the instrument.

Bellows can open to the side or the top, and which type the users have depends on the preference. Many, but not all, of the top opening bellows have tighter bellows springs and require a bit more muscle to pump, but ensure that the internal bellows has lots of air. Many side-pumping bellows have a softer pumping action and can also ensure plenty of air for the instrument.

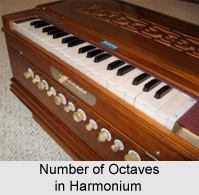

Number of Octaves in Harmonium

Harmoniums are made with differing sized keyboards, which mean that the number of octaves varies from model to model. There can be anywhere form 2.5 - 3.5 (or even more) octaves covered on a model. The models with the shorter keyboards with 2.5 octaves provide plenty of notes for common use. More is not necessarily better because most harmonium players will never use all of the keys on 3.5 octave model. Most models have about 3 - 3.25 octaves.

Stops and Drones in Harmoniums

On the front of the harmonium is usually a series of larger knobs that allow air into the respective air chamber(s). These are called stops. These allow playing one or all of the sets of reeds and controlling the amount of air (volume) to each set of reeds.

Some models have smaller knobs in the front that work the drones. A drone is a fixed note that sounds when you pull the knob to its open position. Most drones are in C#, D#, F#, G#, A#, or a selection of those. It is possible to customize the notes to the preference of the user.

Playing of Harmonium

Some harmoniums push the air and others use suction. The European instruments tend to use pressure, the suction instruments were developed in the United States. In each case, the keyboard is divided into bass and descant sections. Registers are available through "coupling" in just the same way as on pipe-organs. Simple harmoniums have only one register but the larger and more elaborate instruments have up to eleven. When the bellows are worked, air gets compressed in the wooden box below the reeds. The pressurised air is allowed to go across a reed by opening a hole under it. This is done by depressing a key on the keyboard which action moves a valve at the opening under the reed. On the opening of this valve, air rushes past the reed making it vibrate and give the required tone. When the finger is lifted off the key, a spring brings it back to its original position and the aperture below the reed gets closed.

Timbre in Harmonium

Timbre in harmonium plays a major role in the quality of the instrument. The European free reeds were developed early on with a timbral conception that was oriented towards the human voice. The timbral kinship of harmonium and human voice is nowhere as obvious as in Indian music. If early harmoniums were often regarded as having a certain coarseness and hoarseness, all musicians agree without exception that the modern harmonium comes very close to the vocal sound.

Timbre in harmonium plays a major role in the quality of the instrument. The European free reeds were developed early on with a timbral conception that was oriented towards the human voice. The timbral kinship of harmonium and human voice is nowhere as obvious as in Indian music. If early harmoniums were often regarded as having a certain coarseness and hoarseness, all musicians agree without exception that the modern harmonium comes very close to the vocal sound.

Those singers using the harmonium also lauded its ability to adapt its timbre through the basic choice of reeds and the combination of stops. The combination of stops does not refer to the changing of stops during performance, for within the performance of a single piece a change of couplers is extremely rare; what is rather meant is that the sound is adapted to fit the range of the voice, which is done stereotypically: the three sets of reeds a harmonium usually has are called kharaj ("bass"), nar ("masculine") and madi ("feminine"); which refers primarily to the pitch and therefore to the rank of the respective set. Accordingly, a sonorous male voice is accompanied with kharaj, while a softer voice is accompanied with the nar-stop and, if necessary, with a coupled kharaj- or madi-stop. A female voice is usually accompanied with the combination nar- and madi-stops. Just because every singer has his own Sa (i.e. his own voice determines the modal system`s tonic, usually between C and E-flat`) the harmonium is tuned to the according pitch. With a sarangi - or any other stringed instrument - a scordatura would always mean a change in timbre, even if slight.

In Indian music the ideal singing voice has a natural vocal sound; by adapting the instrument to the current register of the voice this natural quality can be enhanced, because the singer does not have to go to vocal extremes to adapt to his accompaniment. This affects the vocal timbre, because the singer does not need to press his voice, for instance, to sing extremely high notes.

Because every singer usually owns a harmonium, or sings regularly with an accompanist who owns a harmonium adapted to his voice, a high level of blending is possible between instrumental and vocal sound. If the sarangi is said to come closest to imitating the human voice, then this rather vague statement can only refer to an area other than timbre; still, when asked, some of the musicians stated that the timbre is meant, without giving any details or reasons.

The harmonium`s superior ability to create a homogeneously blended sound together with the human voice, therefore, is preferred to the sarangi`s superior ability to imitate the more subtle vocal affects. Musically these are two entirely independent areas; accordingly the choice does not mean that one of these areas is rejected. A soloist has to make a choice according to his personal preferences, and this decision is complicated by many other considerations concerning the instrument (e.g. intonation).

Uses of Harmonium

Use of Harmonium in Indian classical music has been immense. This instrument has actually helped people to create music. Interaction between theatre music and non-theatre music was mutual with regard to thumri, seeing that the musicians training naturally did not differentiate between theatre music and non-theatre music. Bhaya Sahib Ganpat Rao (1852-1920) is said to have established the harmonium as a standard accompanying instrument in this genre with parallel sarangi accompaniment and without.

Use of Harmonium in Indian classical music has been immense. This instrument has actually helped people to create music. Interaction between theatre music and non-theatre music was mutual with regard to thumri, seeing that the musicians training naturally did not differentiate between theatre music and non-theatre music. Bhaya Sahib Ganpat Rao (1852-1920) is said to have established the harmonium as a standard accompanying instrument in this genre with parallel sarangi accompaniment and without.

It is interesting that by all evidence, thumri was among the first genres in which the harmonium was embraced: thumri singers were often accompanied and trained by sarangi players, making the sarangi players the core of the genre.

In tracing the relationship between thumri and other musical genres, the harmonium`s path into the "big" genre of khyal comes to light. The aforementioned Bhaya Sahib Rao, who was extremely influential in spreading the harmonium, was a son of the maharaja Jayaji Rao Scindia of Gwalior and a well-known singer, and he came from the direct vicinity of the Gwalior gharana, which was the school (even before the Jaipur gharana) with the earliest and closest ties to the theatre.

Amal Das Sharma and John Napier have described the network structure of Bhaya Sahib`s gharana spanning learning and teaching relationships, over which he could propagate the harmonium at an amazing rate. Thus it seems that by around 1900, the harmonium established itself as a common instrument associated with the "lighter" genres like thumri, ghazal, and also dadra. The repertoire of thumri singers usually spans several genres, also khyal, so that the inspiration by the development in one genre could influence another. One notable aspect of the harmonium`s adoption across musical genres is the fact that this process excluded the transfer of other features even though many women played and propagated the harmonium in thumri, the male dominance in khyal persisted at this time. Manuel notes that many of these khyal singers grew up in the courtesan environment, i.e. they came from families whose male members had the responsibility of training courtesans musically and accompanying them on the sarangi.

Even if the sarangi is still regarded as the instrument "theoretically" most suitable to accompany the human voice, the harmonium today offers a much better alternative for many musicians, solely in terms of tonal colour. The arguments used most often in this context are a certain timbral softness and the possibility to blend the instrumental and the vocal sound through the appropriate selection of reeds. The ideal is to arrive at a blend of voice and accompanying instrument which, in my opinion, is easier to obtain with a free reed instrument than with a bowed instrument, especially in the high register.

The discovery of this affinity between reed and vocal timbre most likely was the prime motivation for high register singers to use and establish the harmonium as an accompanying instrument. The harmonium spread very fast. Whether high or low voice, it is striking that many singers with connections to the courtesan milieu were proteges of the harmonium, and this regardless of genre. In addition to the musical aspect, the sociological perspective again offers an approach: In the 19th century, there was an upward mobility among the sarangi players, i.e. many musicians became more aware of their own musical skills as compared to the vocal soloists skills; the option of becoming a vocal soloist became much more common, while providing sarangi accompaniment moved to the background.

Use of Harmonium with Vocals

Since the beginning of the second half of the twentieth century, the harmonium has been the instrument used most often to accompany singers. The following section explores the strategies that harmonium accompanists have developed to turn their much-criticised instrument into a suitable medium of melodic accompaniment. An examination of recordings of selected ornaments which are especially relevant to the vocal style provides answers. No attempt is made to judge how convincing the respective techniques are; the singer`s general acceptance is sufficient judgement.

Since the beginning of the second half of the twentieth century, the harmonium has been the instrument used most often to accompany singers. The following section explores the strategies that harmonium accompanists have developed to turn their much-criticised instrument into a suitable medium of melodic accompaniment. An examination of recordings of selected ornaments which are especially relevant to the vocal style provides answers. No attempt is made to judge how convincing the respective techniques are; the singer`s general acceptance is sufficient judgement.

Ornaments in Harmonium

An accompanying instrument is supposed to shadow the human voice. This formulation has nearly become a lexical expression; the accompanying instrument is supposed to follow the solo voice as closely as possible, without rivalling it. The intended overall sound ideal is an imitative heterophony between subordinate accompanist and instructive singing voice. The accompanying instrument is, moreover, supposed to "fill in" breathing and other pauses of the singer, thus bridging short periods of time by means of musical ideas that have been provided earlier in the piece by the soloist. When a harmonium is being used, the critical point in this dependency of accompanist on soloist is that technically, the soloist`s "master pattern" and the accompanist`s reproduction thereof have to be rendered in quick succession. This is crucial only when the musical detail in question is a key element of the respective raga that is being performed; otherwise, musical freedom provides ample space for the musician to revert to musical alternatives. In case the melodic idea that is to be imitated by the accompanist is particularly challenging for the harmonium and cannot be imitated faithfully, the temporal proximity of the ideal (vocal) original and the possibly imperfect (harmonium) copy might reinforce the notion that the harmonium is perhaps not the ideal solution. The popularity and intensive use of the harmonium, however, contradict this inference; on the contrary, the appreciation that it receives suggests that measured by its function, the harmonium`s capabilities are satisfactory, and the instrument contributes to the flow of a raga performance. This means that harmonium players must have found effective ways to overcome black-and-white contrasts such as suitable unsuitable by finding musical compromises.

There are several other musical instruments that are being used in contemporary India that pose comparable challenges. If they have mostly been imported rather than developed solely on Indian soil, they do not all derive from the European cultural area: the guitar, the saxophone and others come to mind, but particularly the santur, and in a sense also the sitar, which in recent centuries advanced to being one of the main instruments of Indian solo music. In the case of the sitar, the difficulties that had to be overcome were less obtrusive, but the situation with the santur is directly comparable to that of the harmonium. The tendency to musically exploit an imported musical instrument`s potential by taking it further than this had commonly been done in the originating culture, thus, is evident not only in connection with the harmonium.