During the early modern period traditional Indian medicine could not flourish much. Its development was marred by several critical problems during the rule of the British East India Company. It received a major blow from the Portuguese ruler Garcia-de-Orta. He was the first European who passed an ordinance stating that the Christians under him would not be allowed to consult any local or indigenous physician. The four major problems that cropped up were the opposition of the colonial government and patrons of allopathy, impact of some discoveries made on traditional medicine, conflict between ayurvedic practitioners and the monopoly drug trade of East India Company.

During the early modern period traditional Indian medicine could not flourish much. Its development was marred by several critical problems during the rule of the British East India Company. It received a major blow from the Portuguese ruler Garcia-de-Orta. He was the first European who passed an ordinance stating that the Christians under him would not be allowed to consult any local or indigenous physician. The four major problems that cropped up were the opposition of the colonial government and patrons of allopathy, impact of some discoveries made on traditional medicine, conflict between ayurvedic practitioners and the monopoly drug trade of East India Company.

Traditional Medicine in West Bengal

Traditional medicine could not develop much in West Bengal mainly due to three vital factors, the outbreak of malaria, cholera, small pox and kala-azar, the increasing demand for western medicine and failure of traditional medicine to cure diseases. The East India Company also remained indifferent towards matters of health, disease, and medicine in Bengal. In 1820 the East India Company assumed a dominant role and since then it joined hands with the practitioners of allopathy to curb the practice of traditional medicine. They mainly adopted four chief methods.

They appointed some Indian and European scholars to gather the name of indigenous herbs for British Pharmacopoeia.

Policy to suppress any registration or recommendation for any indigenous medical institutions.

Company`s complete monopoly over the Indian trade and drugs.

Enactment of Poison Act (1914) to abolish the practice.

In 1835 the East India Company suspended the medical classes in the Calcutta Madrassa and the Sanskrit College. On the other hand they appointed few poor scholars and kavirajas who would work for the British Pharmacopoeia. They also began a type of double profitable trade with the indigenous herbs and plants. They purchased indigenous herbs at nominal rates from European factories and later sold them at exorbitant price in the Indian market. The Company passed the Poison Act in 1914 to maintain complete monopoly over Indian drug market. Apart from these the Company also took the decision of not investing money for the development of traditional medicine. They also turned down requests for offering registration to ayurvedic and unani medical institutions, schools, and colleges. Apart from these developments various discoveries like the anatomy (1316), chemotherapy (1493-1541), blood transfusion theory (1625), blood circulation theory (1628), germ theory (1683), physiology (1757-1766), vaccination (1796), penicillin (1928) curbed the growth of traditional medicine.

Furthermore, it was discovered that diseases like cholera, malaria, small-pox, and kala- azare were caused by infection of malignant microbes like plasmodium falciparum for malaria, vibrio cholerae for cholera, leishmania donovani for kala-azar, variola virus for small-pox. These discoveries made during the second half of the nineteenth century raised doubts about the practice of traditional medicine. However, the system could not be uprooted completely. The hostilities helped the practitioners of ayurveda to actively work for the growth of traditional medicine. Acharya Gangadhar Roy and Kaviraj Gangaprasad Sen worked for the progress of ayurveda and Hakim Ajmal Khan, Abdul Majid Khan and Rahim Khan contributed towards the growth of unani medicine. They extensively campaigned for traditional medicine. This helped to enrich the system.

Later Developments of Traditional Indian Medicine

The historical census of 1872 opened new avenues for traditional medicine. In 1920 the University of Calcutta opened a separate department on anthropology under the leadership of the then vice chancellor Sir Asutosh Mukhopadhyay. In 1945  The Anthropological Survey of India was established for conducting research work on the lives of Indian aborigines. The Asiatic Society, the centre for oriental learning also supported the cause. Few freelance European researchers also extended their support through their extensive research work. Some of the notable researchers and their research work were E.T. Dalton`s Tribal History for Eastern India (1872), Rev. P.O. Bodding`s Santhal Medicine (1925), and M. Mc. Alpin`s Conditions of the Santhals. The wide interests of the researchers provided the system with exclusive names such as `folk medicine`, `tribal medicine`, and `ethno-medicine.`

The Anthropological Survey of India was established for conducting research work on the lives of Indian aborigines. The Asiatic Society, the centre for oriental learning also supported the cause. Few freelance European researchers also extended their support through their extensive research work. Some of the notable researchers and their research work were E.T. Dalton`s Tribal History for Eastern India (1872), Rev. P.O. Bodding`s Santhal Medicine (1925), and M. Mc. Alpin`s Conditions of the Santhals. The wide interests of the researchers provided the system with exclusive names such as `folk medicine`, `tribal medicine`, and `ethno-medicine.`

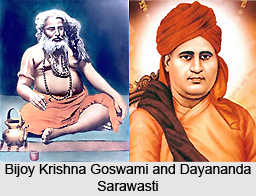

Till the end of the nineteenth century almost no initiative was taken for the development of yogic medicine. Few sahajias and Sufis took interest in this field and under their patronage Amrita Kunda a famous yogic medical text was translated into Arabic and Persian languages. Few experiments were also carried out by Swami Dayanand Saraswati in Punjab and Bijoy Krishna Goswami in Bengal. The harm caused by some western drugs compelled the Indians to turn their attention towards the indigenous medicine. Several clinics and yoga clubs were set up. The Council of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education also included it in their syllabus. Gradually even the western countries developed interest towards it. Presently, yoga has become the centre of interest for the doctors as well as scientists.