Abounded with both Hindu and Muslim shrines and overwhelming forts, Junagadh is home also to forts, some pretty bizarre in its built. History speaks of the mighty and overpowering rulers and of their ruthless conquests. After listening to all the spine tickling myths, one is naturally urged to visit these places, which are generally majestic to their standings.

Abounded with both Hindu and Muslim shrines and overwhelming forts, Junagadh is home also to forts, some pretty bizarre in its built. History speaks of the mighty and overpowering rulers and of their ruthless conquests. After listening to all the spine tickling myths, one is naturally urged to visit these places, which are generally majestic to their standings.

Junagadh is a walled city with the central Dhal Road running through it. Every other road in this town is either meandering or narrow or both. It is thus best to start with Bahauddin (or Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel) Gateway, across the railway station.

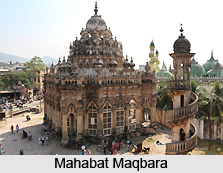

The most outlandish of all Junagadh`s buildings is absolutely the 19th century Mahabat Maqbara, built by Bahadur Khan III for his father Mahabat Khan II. The structure, an amalgamation of Indo-Saracenic, Islamic and European architecture, is truly tremendous. A board next to it calls it `an excellent example of post-medieval Islamic architecture in an Indian environment`. Next to it is the sophisticated Bahauddin Maqbara (constructed in 1878-92) with its refined corkscrew towers straight taken from a fairy tale. A visitor can request someone from the neighbouring Jumma Masjid to open its doors.

In the 19th century Junagadh Palace, near Diwan Chowk, is the Durbar Hall Museum with a remarkable collection of artefacts associated with Junagadh Nawabs. It has chairs and thrones staged in such a manner, as to connote an impending durbar session. On its walls hang portraits, including two of Mahabat Khan III with his dogs donning jewelled collars. Another area has flamboyant brass howdahs and palanquins. There are intricately sculpted female cliauri (plumed fan) bearers being swallowed by fish, and grabbing lions` tails. There is also a gruesome weapon collection, including a walking stick with a small pistol built into its handle.

Entry fee for Indians is Rs. 2, and for foreigners Rs. 50. Visiting is allowed from 9 a.m. -noon and 3 p.m. - 6 p.m. The palace viewing remains closed on Wednesdays and 2nd and 4th Saturdays. Still camera is permitted with a pay of Rs. 2 per click. One necessarily has to remove their shoes at the ticket counter.

The bazaar in front of the Junagadh Palace celebrates late 19th century ostentatiousness with Gothic arches, standing next to Awadhi styled gateways, and surmounted by a European clock tower.

The 19th century Jumma Masjid, with its Gothic arches, chandeliers and colonial ceiling fans, can be easily misidentified for a ballroom, if it wasn`t for the mimbar. The multi-coloured pillars offer a detailed full view.

Near Khapra Khodia lies the 19th century Maqbara of Naju Bibi, a ruthless and powerful begum who briefly ruled over Junagadh in the name of her teenage son. It is fashioned in a markedly indigenous Junagadh style and the dome in reality looks like something close to a UFO.

Next to Naju Bibi`s tomb is Barah Shahid, the graves of 12 martyrs - soldiers of the Tughlaq Sultanate of Delhi who died in a futile ambush against the Rajput ruler of Junagadh. The graves are housed in an oblong, early medieval building.

Visible from Naju Bibi`s maqbara are the 2nd century caves of Khapra Kodia. A former Buddhist monastery, also referred to as Khengar`s Palace, it is a rock edifice, carved into a series of cells, passages and stairways.

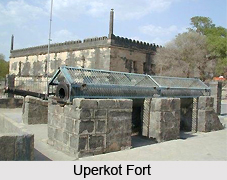

Uperkot, the expansive ancient fort that overlooks the city, is saturated thick with myths. Supposed to date back to the reign of Chandragupta Maurya, it gives Junagadh its name - `Old Fort`. The fort history speaks of 16 sieges. For instance, the 11th century ruler Rah Khengar is remembered for his insolence of Sidhraj of Patan - he had married Sidhraj`s would-be bride, Ranakdevi. Thus snubbed, Sidhraj had laid siege to Uperkot. Local historians allege that the siege had lasted 12 years, after which Sidhraj rampaged the fort and killed Khengar. The Navghan Vav (step-well) in the fort dates back from Khengar`s times. The fort was seemingly deserted between the 7th and 10th centuries before being unearthed again.

The approach path of the fort is through a weirdly tapered gateway with an ancient archway, an excellent example of the Hindu torana. The top of the fort is flat and traversed by paths uniting the principal sites. Inside, on the western wall, are two mammoth cannons, Neelam and Manek. Neelam Tope was moulded in 1531 in Egypt, and is 17 ft in length. It is marvellously wrought and elaborately meticulous (and was likely implausibly destructive in its heyday). The inscription on it makes its function clear, "to fight the incursive Portuguese, who are the infidel enemies of State and religion".

Close by is the 15th century Jama Masjid of the Uperkot fort, erected from the relics of a former Hindu palace, believed to be that of Khengar and Rani Ranakdevi.

A little farther are the Buddhist caves, some going back to 2nd A.D. or even earlier. Coin stashes of the Saka Kshatrapa kings, unearthed during excavations, allude at connections between monastic Buddhism and materialistic trade - monasteries often served as depositories for the guardianship of merchant money. Due to the plethora of western Kshatrapa coins found here, it is inferred that there was a mint.

The caves have a complex cistern system for water. Greco-Scythian style carvings adorn the lower hall, amazingly three storeys underground but open to the sky.

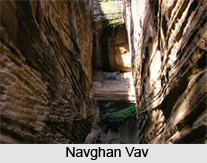

To the east of the caves are two awe-inspiring step-wells. The first is the Adi-Chadi Vav, named after two slave girls of Rah Navghan who are supposed to have constructed it in the 11th century. This looks as much a natural marvel, as a man-made one. The rock is hewn by a narrow, wind-scoured staircase that goes down 100 ft to a broad well. The second, Navghan Vav, steeps even deeper to 170 ft. It is assumed to have been completed in 1060 A.D. It has rock-cut circular stairs going to the bottom, with intermittent apertures in the shaft for light.

It is however not recommended for the timid, the vertiginous or the weak-legged.

It is however not recommended for the timid, the vertiginous or the weak-legged.

The Uperkot fort also has a reservoir dating from the times of the Junagadh Nawabs - with a pumping station still in use and even a few visiting water birds.

Entry fee is Rs. 2 for every visitor. A car rental costs Rs. 25, a two-wheeler costs Rs. 5. Visiting timings are from 8 a.m. - 6 p.m. Entry fee to the Buddhist caves is Rs. 5 for Indians, Rs. 100 for foreigners. Still camera is permitted, but not along with tripod.

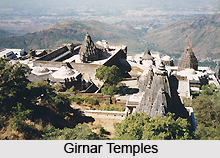

Girnar Hill, rising 3,000 ft over the otherwise flat plain of Sorath, overshadows the horizon and the imagination of Junagadh. The flag of Nawabi Junagadh upheld in the Durbar Hall illustrates a sun rising over a mountain (Girnar) and a lion (from Gir), the emblems of the state. At the foot of Girnar Hill is the rock on which Ashoka`s 14 edicts in Brahmi script are carved. Girnar also pulls in Hindu and Jain pilgrims to Junagadh.

One gets to the historically significant Jain temples, climbing 3,700 steps up the cliff, past some caves, after a dense deciduous forest at the base of the hill. The steps were built in 1889, after funds were collected by circulating a lottery. There are shops for snacks on the way, and the view is simply awe-inspiring. At more than 1,500 ft, after crossing many flashy new constructions, one arrives to what appears like a 16th century fortress, clutching to a cliff-side. This is the Jain temple complex of Girnar.

There are 16 shrines here, with the largest dedicated to the 22nd Tirthankara, Neminath, dating back to the 12th century. Architecturally, the most arresting is the Vastupla Temple, with an image of Mallinath. It is in reality three temples fused together. There are ornate carvings on the exterior and interior. The complex has an air of quietude about it, heightened by the sound of the bells tied to the shikharas of the temples.

There are 16 shrines here, with the largest dedicated to the 22nd Tirthankara, Neminath, dating back to the 12th century. Architecturally, the most arresting is the Vastupla Temple, with an image of Mallinath. It is in reality three temples fused together. There are ornate carvings on the exterior and interior. The complex has an air of quietude about it, heightened by the sound of the bells tied to the shikharas of the temples.

This temple complex is only halfway up Girnar. There are many temples and kumis all the way to the top, all of 7,000 steps, incorporating the Bhairon Jap (from where people would leap to be reincarnated as kings in the next life). Magnificient views of the Junagadh city and the plains beyond can be had to the heart`s content. The perfect time to climb up the hill is just before sunrise, in the comparative absence of pilgrims. Photographing the idols is not permitted.