The Government of India act was the longest piece of legislation ever passed by the British parliament. It was intended to be the basis of an enduring Anglo-Indian raj. But in the event only part of it was put into effect, and that part lasted only two years. The act is of considerable significance. The first significance can be mentioned as because it provided the groundwork for the negotiations that led to the final transfer of power into Indian bands. Secondly, even though the act was conceived as a means of perpetuating British rule, some of its provisions were well drawn up. In later days they were found suitable for inclusion in the constitution of independent India.

The Government of India act was the longest piece of legislation ever passed by the British parliament. It was intended to be the basis of an enduring Anglo-Indian raj. But in the event only part of it was put into effect, and that part lasted only two years. The act is of considerable significance. The first significance can be mentioned as because it provided the groundwork for the negotiations that led to the final transfer of power into Indian bands. Secondly, even though the act was conceived as a means of perpetuating British rule, some of its provisions were well drawn up. In later days they were found suitable for inclusion in the constitution of independent India.

The Government of India act provided for a federation that would include not only the various provinces of British India but also the princely states. A very elaborate division of power was envisaged. Some subjects would be federal i.e. central, others provincial, and still others were `concurrent`. Diarchy was introduced at the centre. This meant that certain `reserved` subjects i.e. defense, external affairs, etc. were to be administered exclusively by the governor general. Up to three appointed counselors were under the custody of governor general.

In the other federal subjects the governor general would be advised by his council of ministers. But even here he kept certain `special responsibilities`. It is clear that under the new act there would be no responsible government at the centre. India was not yet ready for this, the British claimed. The people of the country had heard this many times before. However the point had been reached when the old lame excuses would no longer be accepted.

The proposed central government was to be completed by a bicameral i.e. two-chamber legislature, and a federal court. Representation in both chambers of the legislature was to be weighted in favour of the princely states. The British government looked on the princes as its natural allies, and it strengthened their position in the hope that they would slow down the inevitable movement towards independence. Despite this special treatment, the princes refused to join the federation. As a result, the entire system outlined above was never implemented. However federation would remain a vital question in the years to come.

Of more immediate significance than the federal part of the act of 1935 were the provisions relating to the provinces. Indeed, the most important feature of the entire act was provincial autonomy. This meant that provincial governments exercised complete control over the subjects allotted to them. Diarchy in the provinces, which was the unsuccessful innovation of the act of 1919, was abolished. In every subject governors has to act on the advice of their ministers, who thus had effective control over the provincial administration. The governors appointed ministers, but were responsible to popularly elected legislative assemblies. Therefore could truly be considered the people`s representatives as well.

It would seem that the British had finally surrendered some real power to the people of India. But they were careful to hedge this power around with safeguards. According to the new act, governors kept certain `discretionary powers` and `special responsibilities`. As for example they could dismiss ministers at their discretion. These undemocratic powers became a bone of contention between the British government and the congress after the first provincial elections under the act.

It would seem that the British had finally surrendered some real power to the people of India. But they were careful to hedge this power around with safeguards. According to the new act, governors kept certain `discretionary powers` and `special responsibilities`. As for example they could dismiss ministers at their discretion. These undemocratic powers became a bone of contention between the British government and the congress after the first provincial elections under the act.

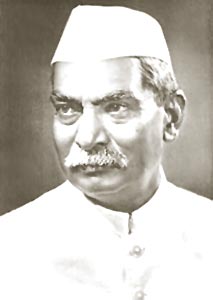

In India the act of 1935 could please very few persons. The princes rejected it because it would have meant the surrender of some of their autocratic powers. But from the point of view of the people of British India these relics of the feudal age had been allotted too much power. Princes would have been able to interfere in the affairs of the provinces, but the people in the provinces would have had no say at all in the affairs of the states. As for the people of the states, they were given no representation whatsoever. Congress president Rajendra Prasad commented in regard to these proposals as `It will be a kind of federation in which unabashed autocracy will sit entrenched in one-third of India and peep in now and then to strangle popular will in the remaining two-thirds.`

Diarchy, which had proved a failure in the provinces, was now going to be tried at the centre. The experience was worse. Representatives of parties other than congress were also disappointed in the act of 1935. The liberal C. Y. Chintamani considered the basis of the act as `a cruel denial of the most cherished aspirations of the people of this country`. The moderate leader Madan Mohan Malaviya said that the statute has a somewhat democratic appearance outwardly, but it is absolutely hollow from inside. Jinnah bluntly called it `thoroughly rotten, fundamentally bad, and totally unacceptable`.

Even many Englishmen could see through the new legislation. During the parliamentary debate, labour leader Clement Attlee summed up his viewpoint by saying that `the keynote of the bill is mistrust`. An English historian has argued that the entire act was a device for safeguarding British financial interests in India. This opinion is given support by a private letter of lord Linlithgow. Later he became the viceroy. He had much to do with the enforcement of the act that he helped to create. Linlithgow wrote that the act of 1935 took the form that it did, "Because we thought that way the best way. Of maintaining British influence in India. It is no part of our policy, I take it... To hurry the handing over of the controls to Indian hands at any pace faster than that which we regard as best calculated, on a long view, to hold India to the empire."

But whatever its limitations, the act of 1935 marked a decisive turning point in India`s constitutional history. Parliamentary institutions, even if in a weakened form, were the framework of the new governmental set-up. The strong element of Indian representation made it certain that these institutions would gradually become stronger. This meant eventual independence, perhaps within a generation.