Tamil Muslims have their origin as per myths, to Arab traders who brought Islam to Tamil Nadu in the seventh century AD. Based in the coastal towns of Tamil Nadu, these Arab traders married local Tamil women whose offspring, a mixed Arab-Tamil race, were the first Tamil Muslims. The entry of Islam through maritime trade made it easier for the religion to be assimilated in south India than in the north, since Arab traders were `not contestants for political power, and consequently were not concerned with maintaining a separate identity.

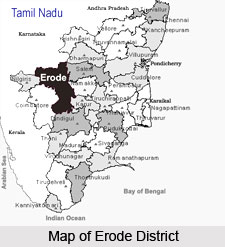

Based on the myths of origin and the areas where they had originally settled, Tamil Muslims were further subdivided into Marakkayars and Rowthers. The term Marakkayar was derived from the Arabic markab, which means boat, and the Tamil rayar, which means king, hence ruler of maritime trade. The two fundamental criteria in the origin myth that define the Marakkayar are that they resided on the coast and were involved in foreign trade. They claimed Arab origin and followed the Shafi School of Islamic jurisprudence. A South-East Asian influence was visible in their dress, customs, and day-to-day life. They were mainly found in the coastal towns of Kayalpattinam, Keelakarai, and Karaikal. Usually big traders, they owned ships that facilitated their business with Ceylon and the Straits settlements. They dealt in pearl, ruby, and chanks. Kilakkarai in Tamanathapuram district, for instance, was famous for its Muslim pearl divers. This stretch along the coastline from Pondicherry to Tirunelveli continues to be addressed in Muslim popular usage as the Marakkayar belt. The Marakkayars defined themselves by their residence on the coast, their participation in maritime trade, their Arab origins, their Shafi belief, and their commonality with South-East Asia.

The term Rowther was connected with horses, either with Muslims as traders or as cavalry. Muslims were known to be the Guthirai-Chettikal or horse traders, who imported Arab horses for trade with the Cholas, the Pandyas, and the Pallavas. Mush of the history of the Muslims until the arrival of the Europeans and their assimilation into Tamil society revolved around the horse trade as well as related duties as part of the cavalry in the military expeditions of these kingdoms. Tamil Muslims and their descendants who had anything to do with horse came to be known as Rowthers. Over time, the Rowthers follow the Hanafi School of Islamic jurisprudence, and were found in the Tamil hinterland, in areas such as Thanjavur, Ramanathapuram, Tirunelveli, and Madurai.

While the Marakkayar and the Rowthers were two clearly identifiable subdivisions among the Tamil Muslims in their origin myths and social organization, another term used for Tamil Muslims was Labbai; its meaning is unclear. What the term labbai meant seemed to depend on who used it; for Tamil-speaking Muslims, especially Rowthers and Marakkayars, labbai referred to a learned Islamic scholar as well as to one who was involved in ritual occupations at the mosques and shrines (derived from the Arabic labbaik, which means `here I am`). The census used the term to signify all Tamil-speaking Muslims, As distinct from Urdu speakers. This improper usage under the colonial census contradicted colonial ethnography, which was aware of the Marakkayar and Rowther distinction. Further, Dakhni Muslims in the region also adopted the colonial category (alternatively described by them as Labbabin) to describe their Tamil-speaking co-religionists. Subsequent reservation policies in education and public employment of the Government of Tamil Nadu from the 1960s onwards adopted the Labbai category.

Apart from the Marakkayar, Rowther, and Labbai, some other divisions in Muslim society have been pointed out by scholars. The Muslim society in Tamil Nadu in the first centuries after the arrival of Islam was composed entirely of converts and their descendants from the indigenous Tamil population. Ethnographers have suggested close connections between particular groups of Muslims and certain Hindu castes. The Rowther were believed to be Maravar converts, the Tarakanar were Iluvan converts, and the Marakkayar were Paravar converts. These intimate interconnections may explain the entrenched sense of similarity that Tamil Muslims felt with their Hindu `caste` fellows and their attractions to the inclusive rhetoric of the Dravidian movement.

Different Tamil Muslim groups were also stratified along class lines. Successful Marakkayar and Rowther merchants were to constitute the political elite of the Tamil Muslim community in the twentieth century. Beneath this powerful, if thin, upper layer of wealthy maritime traders was a mass of artisans engaged in diverse occupations such as weaving, mat making, cotton-tape production, cotton cleaning, pith work, bangle making, the making of perfumes, and the cultivation of betel leaves; wholesale and retail traders in textiles, both for export and the inland market; and a small population of fishermen and pearl divers. It is to this diverse distribution of groups along occupational lines that the category `Tamil Muslim` is applied.

Another important feature of Tamil Muslim society was their dispersal through migration. Over the centuries, they had spread throughout South-East Asia-Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar, Hong Kong, and Indo-China-as merchants, petty traders, and labourers. Tamil Muslim migrants played a key role in the development of Muslim literature and the press in the Tamil language. Tamil Muslim migration to South-East Asia was part of the larger Tamil diaspora, which gave Muslims another opportunity to define themselves as Tamil away from mainland India.

The history of the development of Muslim society in Tamil Nadu made it clear that Tamil Muslims had developed social and cultural ties with the larger Tamil population. Although some Tamils changed their religion, they maintained their linguistic and cultural ties with the larger Tamil population over the generations. Among the most notable events in Tamil Muslim history is the career of the Kilakkarai Marakkayar sitakati (Shaikh Abdul Qadir), who is invoked even to this day by the Tamil literary tradition as a patron of scholars and poets. Sitakati served at the court of the Ramnad Raja, Raghunatha Setupati, and commissioned south India`s best-known Muslim devotional work by Umaru Pulavar, Sirappuranam, a 5, 000 stanza epic on the life of the Prophet. The Marakkayars were among the most active figures in the development of Arabi-Tamil.

Muslims formed an integral part of the Tamil cultural landscape. Non-Muslims joined Muslims in celebrating Muharram or Allah-Sami pandiki and reveled in the fire-walking ceremony, the wearing of masks, and participating in tomb cults that would, according to orthodox criteria, be, in the words of an official, `violative of the principles of Islam`. In Tiruchirapalli, for instance, Muslims enjoyed a unique relationship with three non-Muslim castes: the Kammalans, the Tottiyans, and the Pallans. These castes and the Muslims were known to assist each other in times of trouble, and the terms of address between them were those usually reserved for immediate kin. Muslims and Kammalans called each other mani, by which they meant `paternal uncle`; Muslims addressed Pallans as `grandson` and `granddaughter`, and were called `grandfather` by them; and finally, Tottiyans and Muslims addressed one another as maman or maternal uncle. Such locality-based social formations where Muslims greeted others and were greeted in turn as kin rendered unfeasible the development of rigid `Hindu` and `Muslim` boundaries in Tamil Nadu.

The most important factor is that the Muslim politics subsumed the categories of Marakkayar, Rowther, and Labbai under the category of Tamil Muslim. Even if the origin myths and occupations determined social relations among Tamil Muslims, what must be noted is that these categories carried little relevance in the larger political processes in the region. The Tamil language and Islam were the main parameters of definition for these groups and therefore there is the importance of defining them as Tamil Muslims. Any account of Tamil Muslims shows that they had a long tradition of being Tamil while being Muslim. This was achieved through conversions, spatial location within Tamil society, and involvement with and contribution to the Tamil language. This sense of being Tamil later came to the forefront when Tamil Muslims negotiated the Dravidian movement and Indian nationalism.