Sutradhars are the people who announce the subject matter in the Ankiya Nats.

Like the Sanskrit drama most of the Ankiya plays open with preliminaries prescribed in the orthodox Natya-Sastra (dramaturgy), namely, nandi, prarocand and prastavana.

In earlier Assamese Dramas, there are usually two nandi verses with 8 or 12 feet of verse or carana; one of this is of a benedictory nature and the other suggests the subject-matter of the play. Some of the later plays totally discarded the nandi verse in Sanskrit language and in its place introduced a benedictory poem in Assamese. In Sanskrit Drama, the general stage direction, nandyante sutradhara, brings the Sutradhara after the nandi, which implies that the nandi was not recited by the Sutradhara. But in the Ankiya plays, the Nandi recital is the specific function of the Sutradhara.

The nandi being over, the Sutradhara announces the subject-matter of the play in a Sanskrit verse (prarocand). This is invariably accompanied by a long poem in Assamese called bhatima. After that follows the prastavana. The Sutradhara hears a celestial sound. On this point a discussion arises, and as it progresses the Sutradhara announces the names of the approaching personages. At the end of this discussion the companion (sangi) retires from the stage.

The Sutradhara apart, there appear two other additional characters in an Assamese play, namely the Duta and Bahuva They are, however, outside the category of the dramatic personnel, and they are introduced in actual performances of the play to serve as heralds and to provide comic relief.

The Duta and Bahuva appear on the stage to explain the reasons for eventual interruptions in the progress of the play. They also announce the change of scene and the entrance of new characters on the stage.

The Bahuva has other duties too; besides filling in gaps in the narration he is to relieve the monotony and amuse the audience as best as he can by his skits and jokes which he himself invents, of course, in rigid conformity with traditional practices. He, however, is never allowed to interfere with the organic part of the play. Just as the play begins with a characteristic benediction, so it ends with a prayer in Assamese called mukti-mangal bhatima, where, the sutradhara begs forgiveness of God for any faults of omission or commission in the management of the drama. Lastly, he emphasises the moral effect of the play, and desires his audience to follow the path of righteousness.

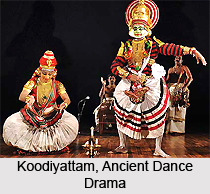

The most striking feature of the staging of an Ankiya Nat is the co-ordination and harmony of the four elements song, rhythmic representation by dance, melody emanating from appropriate instruments, and dialogue. In an Assamese play, Bhavana, all the characters move rhythmically from the beginning to the end, in the form of dancing with appropriate steps, gestures and abhinaya (dramatic) postures. In short, the whole narration of the story progresses through dances, and dancing is considered one of the best arts for awakening feeling. It may be said that the Assamese dramatic performance consists mainly of movements of the limbs, rhythm forming an essential part.

In this dance-drama, the Sutradhara is the principal dancer. After the recitation of the nandi, the Sutradhara interprets the story and the sentiments embodied in the sloka by appropriate dance. This is done by the Sutradhara all through the play. The major three dance-forms of an Ankiya Bhavana are Sutradhara-nac (dance of Sutradhara), Krsna-nac (dance of Lord Krishna), and Gopi-nac (dance of the milkmaids). Other forms of dances are Rasa-nac, Natuvanac and Cali-nac; all are more or less adapted from classical texts on dancing.