Starfish, the most well-known and typical echinoderm, is common at low-tide mark, moving over sand or sides of rocks. Its shape is star like with a central disc from which five tapering arms radiate. It has no head but can move in the direction of any arm. The upper surface of the animal is convex and the underside flat. At the centre of the flat surface is a five-sided aperture containing the mouth. The corners of the aperture are produced as a groove along the mid-longitudinal line of each arm. Each groove is lined on either side by one or two rows of tube-feet. Each tube-foot is a short vertical tube with a sucker below and a small bladder (ampulla) above. The grooves with their numerous tube-feet on either side resemble miniature garden paths and hence are called ambulacral grooves. The arms and tube-feet are furnished with muscle fibres. The entire body of a starfish is protected by a tough, hard crust containing numerous limy (calcareous) plates called ossicles (small bones) embedded in soft flesh. This skeleton is not strictly rigid but somewhat flexible, for the ossicles are only loosely joined by connective tissues and muscles. The animal can therefore bend and twist its arms with ease. The ossicles are numerous, arranged regularly around the mouth region, in the ambulancral grooves and along the sides of the arms. Over the other parts they are scattered. Sharp spines, rigid and movable, project from the ossicles covering the back and sides of the arms. Surrounding the spines there are certain pincer-like structures called pedicellarias. In the living animal these pedicellarias continually twist and snap, picking out and cleaning dirt and debris off the exterior. They aid in keeping the respiratory and other pores from getting blocked and also in catching prey.

Starfish, the most well-known and typical echinoderm, is common at low-tide mark, moving over sand or sides of rocks. Its shape is star like with a central disc from which five tapering arms radiate. It has no head but can move in the direction of any arm. The upper surface of the animal is convex and the underside flat. At the centre of the flat surface is a five-sided aperture containing the mouth. The corners of the aperture are produced as a groove along the mid-longitudinal line of each arm. Each groove is lined on either side by one or two rows of tube-feet. Each tube-foot is a short vertical tube with a sucker below and a small bladder (ampulla) above. The grooves with their numerous tube-feet on either side resemble miniature garden paths and hence are called ambulacral grooves. The arms and tube-feet are furnished with muscle fibres. The entire body of a starfish is protected by a tough, hard crust containing numerous limy (calcareous) plates called ossicles (small bones) embedded in soft flesh. This skeleton is not strictly rigid but somewhat flexible, for the ossicles are only loosely joined by connective tissues and muscles. The animal can therefore bend and twist its arms with ease. The ossicles are numerous, arranged regularly around the mouth region, in the ambulancral grooves and along the sides of the arms. Over the other parts they are scattered. Sharp spines, rigid and movable, project from the ossicles covering the back and sides of the arms. Surrounding the spines there are certain pincer-like structures called pedicellarias. In the living animal these pedicellarias continually twist and snap, picking out and cleaning dirt and debris off the exterior. They aid in keeping the respiratory and other pores from getting blocked and also in catching prey.

The starfish has an extensive internal cavity (coelom) which protects all the important internal organs. It is lined by a membrane and contains sea water mixed with albuminoids. This fluid takes in Oxygen and releases Carbon Dioxide through respiratory openings. It also collects and excretes waste matter.

The locomotory apparatus and its working are unique in the starfish. The mechanism is hydraulic, run by the water-circulating system of the animal. Lying between two arms of the starfish, a little to one side near the centre of the back, is a perforated disc of sieve-plate (madreporita) leading into a short vertical limy tube - the stone canal - which opens into a ring canal surrounding the mouth. From the ring canal radiate five radial canals, one along each arm. By short side branches the radial canals are connected to each tube-foot. Filtered sea water passes down through the stone canal into the ring canal and then into the radial canal. The bladders connected to the tube-feet also get filled with water. This distension at the upper parts of the tube-feet creates a vacuum at the lower ends, which act as suckers and hold fast. The distended bladders then contract and push the water down into the tube-feet. This removes the vacuum and releases the suckers. By the combined muscular action of the arms and the alternate distension and contraction of the bladders the animal walks on its tube-feet.

The mouth opens through a short throat into a capacious five-lobed sac - the cardiac division of the stomach. The walls of the sac have muscle fibres which can stretch or contract. If the animal finds an oyster or muscle too large for its mouth it thrusts out the cardiac portion of its stomach through the mouth and engulfs the prey and after digesting it the retractor muscles work and the stomach is drawn in. Next to the cardiac division is the pyloric division of the stomach which first projects as a short tube into each of the arms and then bifurcates into a pair of branches bearing a series of glandular pouches which secrete a digestive fluid. The pyloric division is followed by the intestinal or rectal division which is also five-pouched. The rectum finally opens out through the anus on the back of the animal.

The mouth opens through a short throat into a capacious five-lobed sac - the cardiac division of the stomach. The walls of the sac have muscle fibres which can stretch or contract. If the animal finds an oyster or muscle too large for its mouth it thrusts out the cardiac portion of its stomach through the mouth and engulfs the prey and after digesting it the retractor muscles work and the stomach is drawn in. Next to the cardiac division is the pyloric division of the stomach which first projects as a short tube into each of the arms and then bifurcates into a pair of branches bearing a series of glandular pouches which secrete a digestive fluid. The pyloric division is followed by the intestinal or rectal division which is also five-pouched. The rectum finally opens out through the anus on the back of the animal.

The food of starfish includes fish, molluscs, worms, crabs etc, and even garbage and decaying matter. A starfish has nerve-cells scattered on its outer layer, a nerve-ring round the mouth, a nerve-cord along each arm supplying nerve-fibres to the tube-feet. At the tip of each arm is a pigmented mass which works as an eye.

There are separate female and male starfish. The sexual cells are produced by a pair of special organs at the base of each arm. The cells when mature are let out through pores in outside water. The zygote (fertilized egg) divides and forms a ciliated bilateral larva which for some time swims and later sinks to the sea bottom where it first becomes a tiny rosette and then changes onto a small starfish with five knobs. It goes on growing for a year or two, strengthening the knobs into pointed rays, and eventually becomes an adult starfish.

Starfishes have the power to grow lost parts. Arms which get mutilated are redeveloped in a short time. Even it two or three arms and a part of the disc are destroyed the animal regenerates them in the course of a month.

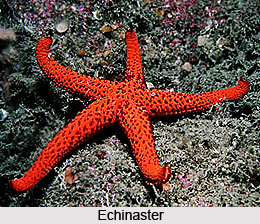

Starfishes are great destroyers of shellfish. Since they consume garbage and decaying matter they are good scavengers of the seashore. Cod, haddocks and larger sea animals feed on starfishes. There are more than twenty families of starfishes. In some the number of arms is many - about forty. In some the disc alone is prominent with short blunt arms. Mostly they are of reddish or copper colour but grey, ochre, scarlet and purple varieties are also common. They range in size from eight to eighty centimetres. Echinaster, Asterias, Astropecten and Anthenea are common Indian genera.