In Buddhist phenomenology and soteriology, the five skandhas (Sanskrit) or khandhas (Pali) are five "aggregates" which categorise all individual experience, among which there is no "self" that can be found. A frequently asserted metaphysical corollary is that a "person" is made up of these five aggregates.

In Buddhist phenomenology and soteriology, the five skandhas (Sanskrit) or khandhas (Pali) are five "aggregates" which categorise all individual experience, among which there is no "self" that can be found. A frequently asserted metaphysical corollary is that a "person" is made up of these five aggregates.

In the Theravada tradition, suffering originates when one identifies with or otherwise clings to an aggregate; thus, suffering is eliminated by renouncing attachments to aggregates. The Mahayana tradition additionally puts forth that ultimate freedom is realised by deeply pervading the inherently empty nature of all aggregates.

Outside of Buddhist didactic contexts, "skandha" can mean mass, heap, pile, bundle or tree trunk.

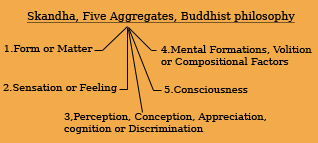

Buddhist doctrine distinguishes five aggregates:

• "form" or "matter" (Sanskrit, Pali rupa):

external and internal matter. Externally, rupa is the physical world. Internally, rupa comprises the material body and the physical sense organs.

• "sensation"or "feeling" (Sanskrit, Pali vedana):

sensing an object as either pleasant or unpleasant or neutral.

• "perception", "conception", "apperception", "cognition" or "discrimination" (Sanskrit samjña, Pali sanna):

registers whether an object is recognised or not (for example, the sound of a bell or the shape of a tree).

• "mental formations", "volition", or "compositional factors" (Sanskrit samskara, Pali sankhara): all sorts of mental habits, thoughts, ideas, opinions, impulsions, and decisions sparked by an object.

• "consciousness" (Sanskrit vijñana, Pali vinnana):

(a) In the Nikayas: cognisance.

(b) In the Abhidhamma: a series of speedily changing interconnected disconnnected acts of cognisance.

(c) In Mahayana sources: the root that supports all experience.

In the Pali Canon, the majority of discourses concentring on the five aggregates discusses them as a foundation for understanding and attaining release from suffering, without describing relationships between the aggregates themselves. However, from some canonical preachings, a causal relationship between the five aggregates can be deduced.

The following exemplify such relational dimensions:

Form (rupa) originates from experientially irreducible physical/physiological phenomena.

Form - in terms of an external object (like a sound) and its connected internal sense organ (like the ear) - gives rise to consciousness (viññ?na).

The concurrence of an object, its sense organ and the associated consciousness (viññana) is called "contact" (phassa).

From the contact of form and consciousness originate the three mental (nama) aggregates of feeling (vedan?), perception (sañña) and mental formation (sankhara).

The mental aggregates can then in turn give rise to additional consciousness that leads to the developing of additional mental aggregates.

In this outline, form, the mental aggregates, and consciousness are mutually dependent.

Other Buddhist literature has described the aggregates as arising in a linear or progressive mode, from form to feeling to perception to mental formations to consciousness.