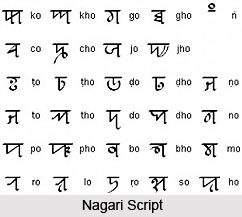

Siddham script is also admired in Sanskrit, standing for "accomplished" or "perfected". Siddham is essentially the name of a North Indian script, used for penning Sanskritic compositions during the period ca 600-1200 C.E. Known to have descended from an illustrious line up of primeval Indian scripts like the Brahmi script and later through the Gupta script, Siddham script also gave rise to the Devanagari script as well as a number of other Asian scripts like Tibetan script. However, in present times, Siddham is spelt in several different spellings, almost all of which stands for one and the same meaning. Siddham script is an enhancement upon the script employed during the times of Gupta Empire reigning in India. The name originated from the practice of writing the word Siddham or rastu (`may there be perfection`) at the beginning of every document.

Siddham script is also admired in Sanskrit, standing for "accomplished" or "perfected". Siddham is essentially the name of a North Indian script, used for penning Sanskritic compositions during the period ca 600-1200 C.E. Known to have descended from an illustrious line up of primeval Indian scripts like the Brahmi script and later through the Gupta script, Siddham script also gave rise to the Devanagari script as well as a number of other Asian scripts like Tibetan script. However, in present times, Siddham is spelt in several different spellings, almost all of which stands for one and the same meaning. Siddham script is an enhancement upon the script employed during the times of Gupta Empire reigning in India. The name originated from the practice of writing the word Siddham or rastu (`may there be perfection`) at the beginning of every document.

Grammar of Siddham Script

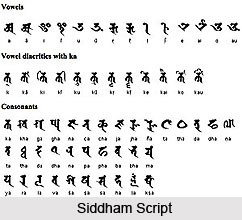

Siddham script is an abugida (standing for each letter exemplifying a consonant, whereas vowels are written with obligatory diacritics) or `alphasyllabary` as opposed to an alphabet. This happens due to each character indicating a syllable, but not encompassing every possible syllable. If no other mark comes about, then the short `a` is adopted and espoused. Diacritic marks designate the additional vowels, the pure nasal (anusvara) and the aspirated vowel (visarga). An extraordinary mark (virama) may be employed to designate that the letter stands alone with no accompaniment of vowel, which sometimes is the case at the termination of Sanskrit words.

Reading and writing a Siddham script calls for not only grasping the elementary vowels and consonants, but also learning how to amalgamate vowels with consonants, including how to cope with double and conjunct consonants. Examples of the last kind include: tta, mma, and rma, kya etc. Sanskrit also encompasses the vowels utilised by Siddham, but these are hardly ever employed in mantras and are often omitted from the alphabetical order in Siddham.

The Siddham script strictly utilises vowels and consonants, essentially including the ones designated during the Gupta rule.

The vowels are - a, i, u, r, e, ai, o, au

Vowel diacritics with ka - k, ka, ki, ku, kr, ke, kai, ko, kau

Consonants - ka, kha, ga, gha, na, ca, cha, ja, jha, ta, tha, da, dha, pa, pha, ba, bha, ma, ya, ra, la, va, sa, ha, ksa

Use of Siddham Script

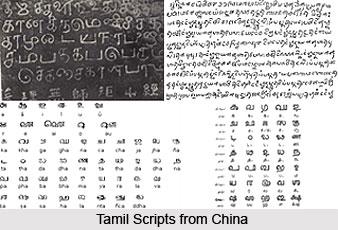

Several of the Buddhist texts which were carried forth to China along the Silk Road (also popular as Silk Routes, the pathways are a wide-ranging interconnected network of trade routes spanning the Asian continent) were penned using a version of the Siddham script. This chain network continued to develop and negligible variations are still witnessed across time and in umpteen regions. To state more importantly, the script was employed to carry and transfer the Buddhist tantra texts. The time that is being spoken of, it was deemed important to preserve the pronunciation of mantras and Chinese was not regarded as fit for writing the sounds of Sanskrit. This unique and intelligent movement led to the withholding of the Siddham Script in East Asia. The practice of writing exploiting Siddham survived in East Asia, where Tantric Buddhism is also known to have thrived consistently.

Kukai (also hugely esteemed posthumously as Kobo-Daishi, 774-835, he was a Japanese monk, scholar, poet and artist) was the man to introduce the Siddham script in Japan when he returned from China in 806. Kukai had studied Sanskrit in China with Nalanda-trained monks, together with one recognized as Prajna. By the time Kukai had studied and memorized this script, trading and pilgrimage routes traversing land to India were closed by the expansion of Islamic empire of the Abbasids.

Influence of Siddham in India

The influence of Siddham in India dates back to its introduction in the 9th century, when it held a prominent place in religious texts and manuscripts. However, a series of purges of "foreign religions" in China during the same period disrupted the flow of Siddha? texts to Japan, leading to its decline in East Asia while it continued to flourish in India.

Over time, Siddham faced competition from other scripts like Devanagari in India. In the northeastern regions, a derivative known as Gaudi evolved into scripts such as Eastern Nagari, Tirhuta, Odiya, and Nepalese, further diversifying the script landscape of South Asia. This left East Asia as the sole region where Siddham remained in use.

Japanese Buddhist scholars, faced with the challenge of interpreting Siddham texts without access to the original sources, developed innovative approaches. Similar to the adaptation of Chinese characters, they sometimes created multiple characters with the same phonological value to add layers of meaning to Siddham characters. This blending of Chinese and Indian writing styles allowed for differential interpretations of Sanskrit texts written in Siddham, akin to the practices adopted with Chinese characters.

Consequently, a multitude of variants of the same characters emerged, reflecting the dynamic interaction between cultures and languages in the transmission of Siddham scripts. Despite its decline in some regions, the legacy of Siddham endures in various forms, highlighting its enduring impact on the cultural and linguistic landscape of India and beyond.

Present Position of Siddham script

Leaving all such promising hindrances aside, Siddham script is still basically represented as a hand-written script. The contemporary age has endeavoured to thrust some efforts to create computer fonts of this ancient inscription, though till date none of these are capable of reproducing all of Siddham conjunct consonants just as it was previously.