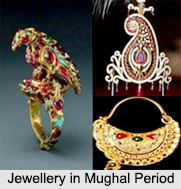

Extravagance, romance and beautiful originality are the suggestive words to describe the era of the Mughal emperors. A sensation of magnificence have been created with the fables of fabulous jewels, handsome princes, beautiful women and perfumed palaces, that continues to hang back long after the end of the dynasty in 1858. The Mughals were considered to be the great patrons of the arts, and artists during that time were highly respected and encouraged.

Extravagance, romance and beautiful originality are the suggestive words to describe the era of the Mughal emperors. A sensation of magnificence have been created with the fables of fabulous jewels, handsome princes, beautiful women and perfumed palaces, that continues to hang back long after the end of the dynasty in 1858. The Mughals were considered to be the great patrons of the arts, and artists during that time were highly respected and encouraged.

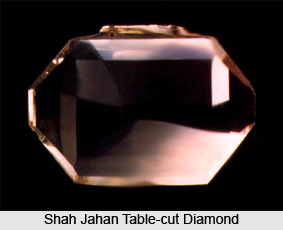

To make a replica in their paintings, painters were often permitted to examine at close quarters priceless jewels and textiles belonging to the emperors. In the story of the Shah Jahan Table-Cut diamond one of these delicate diminutive paintings is especially momentous.

In the early second half of 20th century "a spectacular historic table-cut diamond" was offered for auction in Geneva by Christie. At that time the gem was weighing 56.70 carats, octagonal in shape with noticeably drilled holes. Before the sale, E A Jobbins and Dr R R Harding of the Institute of Geological Sciences inspected it. During the course of the examination, an incredible connection between the diamonds they were examining and a Mughal miniature painting dated 1616-17, was made. The miniature displayed in the Victoria & Albert Museum. This painting is a representation of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan holding a `sarpech` i.e. turban ornament or aigrette in his left hand and pointing to it with his right. That pointed beautiful jewel is made of gold and has decorated.

Within its arabesque border, a cushion-shaped apple green emerald and an octagonal table-cut diamond were present. From the crown of the emerald mounts a steep of coiled gold where each stalk ends in a pearl globule. The stone that was being examined by the two gemologists closely matched the diamond in the jeweled ornament. When Shah Jahan`s hand holding the `sarpech` was enlarged, this similarity became even more noticeable. The dimensions and the shape both of the gem in the painting matched those of the table-cut diamond being studied. This was the Shah Jahan Table-Cut incontestably.

From the accounts of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a reference to the diamond can be found. Aurangzeb became the Mughal emperor in 1658, after swearing his father Shah Jahan. Tavernier went to Aurangazeb`s court to pay his respects on November 2, 1665. Chief of the emperor`s treasury, Akel Khan, on that occasion showed him some of the royal jewels. in addition to the Great Mughal the collection included ``another diamond of pear shape of very good form and fine water, with three other diamonds, table-shaped, two of them clean and the third with some little black specks. Each weighs fifty-five to sixty ratis, and the pear sixty-two and half."

The 19th-century London jeweler, Edwin Streeter, with his authority on diamonds and gemstones, states in his book, `The Great Diamonds of the World`, that echoed to Tavernier`s calculations, the weight of the three table-cut stones in Aurangzeb`s treasury would have been from 48 to 52 (old) carats. From Christie`s sale catalogue a reference to this was taken that it is nearly unfeasible to verify the correctness of Tavernier`s assessment of the gems, which was made more than three centuries ago. According to Streeter`s suggestion the attempt was made to prove that in all probability the beautiful diamond was part of the booty taken away to Persia by the villainous Nadir Shah after the rucksack of Delhi in 1739. Nadir Shah in 1741, with several priceless gifts sent his representative to Russia for the newly promulgated Empress Elizabeth. There were huge trays packed high with jewellery. Among them with high possibility one carried the Shah Jahan Table-Cut diamond. It is possible that one of the tsars or tsarinas later presented it to someone.

The gem reappeared in London more than a hundred years later. The world`s most distinguished and beautiful jewellery was displayed at the Great Exhibition in one mordant summer of 1851, which was held in Hyde Park. `The Times` elaborately reported the event -- "In the British department, among the gorgeous and costly display of jewellery and gold and silver plate, there is a small case which attracts considerable attention. It contains imitations in crystal of all the largest diamonds in the world."

The Shah Jahan Table-Cut remained unsold at the 1985 Christie`s sale. The retailer announced that his family acquired it in 1893. Later it was sold privately and is now owned by Sheikh Nasser Al-Sabah of Kuwait.