The government reacted to the second phase of the civil disobedience movement with the most severe measures of repression that it yet had resorted to. Congress was again outlawed, and more than a lakh of persons were arrested. The inhuman treatment meted out to men, women and also children. One may sum up using the words of a report compiled by an independent English organization, `In 1932 the ordinances and now the acts recently passed deprive the Indian people of the rights of personal freedom and safeguard which, most British people believe, exist under British law everywhere.

The government reacted to the second phase of the civil disobedience movement with the most severe measures of repression that it yet had resorted to. Congress was again outlawed, and more than a lakh of persons were arrested. The inhuman treatment meted out to men, women and also children. One may sum up using the words of a report compiled by an independent English organization, `In 1932 the ordinances and now the acts recently passed deprive the Indian people of the rights of personal freedom and safeguard which, most British people believe, exist under British law everywhere.

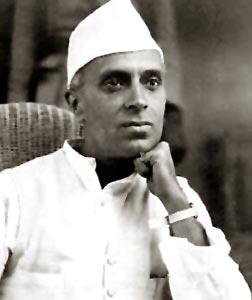

The Indian people refused to be cowed into submission. There was picketing of cloth and liquor shops, salt satyagrahas, forest-law violations, and nonpayment of rent and of revenue. The national flag was hoisted in many places. The banned congress held an illegal session in Delhi, and congress activities went on despite police arrests. But it was difficult to keep up a high pitch of enthusiasm over a long period of time. Jawaharlal Nehru has commented, `the initial push of inspiration was far less than in 1930. It was as if we entered unwillingly into battle. There was a glory about it in 1930, which had faded two-years later`.

Yet the people persisted until finally the movement was suspended by Gandhiji in may 1933.

The civil disobedience movement demonstrated that the Indian people were willing to struggle and suffer to reach their goal of independence.  But the British still held power, and they were determined to keep it as long as they could. They would listen only to `moderate` demands for dominion status; accept only `moderate` constitutional methods. The movement had made it clear that the rulers could not govern effectively without the people`s co-operation. But the government`s policy of repression compelled the people to draw back from direct confrontation, and to carry on the struggle at the negotiating table and in the council hall.

But the British still held power, and they were determined to keep it as long as they could. They would listen only to `moderate` demands for dominion status; accept only `moderate` constitutional methods. The movement had made it clear that the rulers could not govern effectively without the people`s co-operation. But the government`s policy of repression compelled the people to draw back from direct confrontation, and to carry on the struggle at the negotiating table and in the council hall.

At the same time that the civil disobedience movement was altering the balance of power in India, work was progressing in London on a new `constitution`. It was intended to keep as much control as possible in the hands of the British. Many years went into the making of this reactionary document. The Simon commission had been the first step. The commission`s report was submitted in 1930. It provided the basis for the discussions at the round table conferences.

In March 1933, the government published its conclusions in a white paper. This was considered over the next few months `by a joint select committee` made up of members of both houses of the British parliament. Some `safe` Indian delegates were nominated by the government to take part in these deliberations. But they sat in as consultants and not as members, and so had little effect on the proceedings. A bill based on the white paper was introduced in the British parliament on 19 December 1934. There followed many months of strenuous debate. During this the conservative `diehards`, led by Winston Churchill tried to give to the new statute a form that would have been even less acceptable to Indians than the one finally adopted. The bill became law in August of the next year as the government of India act, 1935.