During the first three centuries of the contemporary era, the workshops of Gandhara and Mathura had created virtually all the surviving freestanding stone sculptures, together with style. A handful of works, predominately yaksis, in styles allied to Mathura, were found as Far East as Patna. For images of the Buddha, both standing and seated, exports from Mathura itself were relied upon. The Kanoria Parsvanatha stele, from Patna, was commonly held to be from the late 4th century, and the fragmental inscription of Rajgir, the seated Neminatha, may be attributed to the reign of Chandragupta II (c.377-414), due to the manner in which the lower garment of the standing attendee figure terminates just above the knees, with four audacious ripples descending between the legs. Both manifests the preliminary stages of a style which had climaxed during the post-Gupta Buddhas of Nalanda, but not, interestingly enough, the great Gupta Buddhas of Sarnath, confessedly further to the west. The legendary seated Buddha from Bodh Gaya, dated in the year 64 of an anonymous king who presumably reigned within the Gupta period (i.e. 320 + 64 = A.D. 384), is one of the central pieces in the long history of Indian sculpture. It was long assumed to be an import from Mathura, because the body was in the same position as the Katra-type Buddhas created there, the pleats of the robe were crowded together in a likewise manner, and its throbs with their immense physical vivacity. But the head was rather unusual- the face was threatening, heavy lidded, the eyes concentrated the end of the nose- an over-the-top controlling evocation of the Buddha as the great yogi. According to Stella Kramrisch`s words, it is `the first image in India which by its form signifies what its name implies`.

During the first three centuries of the contemporary era, the workshops of Gandhara and Mathura had created virtually all the surviving freestanding stone sculptures, together with style. A handful of works, predominately yaksis, in styles allied to Mathura, were found as Far East as Patna. For images of the Buddha, both standing and seated, exports from Mathura itself were relied upon. The Kanoria Parsvanatha stele, from Patna, was commonly held to be from the late 4th century, and the fragmental inscription of Rajgir, the seated Neminatha, may be attributed to the reign of Chandragupta II (c.377-414), due to the manner in which the lower garment of the standing attendee figure terminates just above the knees, with four audacious ripples descending between the legs. Both manifests the preliminary stages of a style which had climaxed during the post-Gupta Buddhas of Nalanda, but not, interestingly enough, the great Gupta Buddhas of Sarnath, confessedly further to the west. The legendary seated Buddha from Bodh Gaya, dated in the year 64 of an anonymous king who presumably reigned within the Gupta period (i.e. 320 + 64 = A.D. 384), is one of the central pieces in the long history of Indian sculpture. It was long assumed to be an import from Mathura, because the body was in the same position as the Katra-type Buddhas created there, the pleats of the robe were crowded together in a likewise manner, and its throbs with their immense physical vivacity. But the head was rather unusual- the face was threatening, heavy lidded, the eyes concentrated the end of the nose- an over-the-top controlling evocation of the Buddha as the great yogi. According to Stella Kramrisch`s words, it is `the first image in India which by its form signifies what its name implies`.

The seated Buddha from Mankuwar in eastern Uttar Pradesh, dated 429, exhibits the influence of the comparatively contemporary styles in Mathura, with its low base, assuming a central chakra and two frontal-facing lions. The face, though more circular, also depicts some of the rigorousness of the 5th century Mathura Buddhas. Undoubtedly, the supreme Hindu image of the Gupta period thus far known from the eastern Madhyadesa, is the colossal 6ft. Krishna Govardhana (Krishna holding up the Guardian Mountain) from Varanasi, now preserved in Bharat Kala Bhavan. The arms have been reestablished, not unproductively, though they are possibly a shade too gigantic. The young prince (kumara) Krishna wore the archetypal pair of tiger`s claws, (vyiighra nakha) on his necklace, a low crown and three locks of hair (trisikhin), the customary marks of Kartikeya (Skanda) and of the Bodhisattva Mafijusri, all exhibited as kumaras. The lower torso and stomach possesses the Sarnath sensitivity, a hardly discernible roll of flesh bulging out above the squeezing top of the dhoti. The large round face, and the not very deep set eyes are still resonant of Udayagiri.

One of the most endearing Indian sculptures is the Gadhwa `lintel` frieze, its charm possibly heightened by the doubtfulness environing its purpose and themes. In the midpoint of the long narrow carving, stands Vishnu Visvarupa, in one of his emanatory forms. At one end stands Surya, the sun god, in his chariot on the backdrop of a circular disc, while at the other end stands Chandra (the moon), seated with his consort on a hemispherical moon. Towards the left, a long parade of musicians, young girls and others carrying food, curves its way, behind a figure kneeling at the feet of Vishnu, a sunshade referring high rank held over his head. On the opposite side, with additional gifts of food, another parade approaches, including a burly soldier with a hefty amount of hair, carrying a sword, tallying a Nepalese kukri. At its head is a statuette, also fêted by a sunshade. They are adjoined by two others, emerging from a building, plausibly a dharmaiiilii, or pilgrim`s hall, in which bending figurines are being fed by women, wearing a distinguishing head-cover, that comes down under the chin. The Gadhwa lintel is discerned by the nonexistence of wholly ornamental elements (no jewellery even is present) and by the dexterous metrical insertion and variety of stances of the procession- work of a superior sculptor `unusually adept in representing three-dimensional poses, with an exceptionally slender canon of proportions`. On stylistic justifications, the lintel would seem to belong to the latter part of the reign of Kumaragupta (C. 414-55), whose inscriptions appear at the place with others of Gupta date. It exemplifies the peak of Gupta narrative relief.

One of the most endearing Indian sculptures is the Gadhwa `lintel` frieze, its charm possibly heightened by the doubtfulness environing its purpose and themes. In the midpoint of the long narrow carving, stands Vishnu Visvarupa, in one of his emanatory forms. At one end stands Surya, the sun god, in his chariot on the backdrop of a circular disc, while at the other end stands Chandra (the moon), seated with his consort on a hemispherical moon. Towards the left, a long parade of musicians, young girls and others carrying food, curves its way, behind a figure kneeling at the feet of Vishnu, a sunshade referring high rank held over his head. On the opposite side, with additional gifts of food, another parade approaches, including a burly soldier with a hefty amount of hair, carrying a sword, tallying a Nepalese kukri. At its head is a statuette, also fêted by a sunshade. They are adjoined by two others, emerging from a building, plausibly a dharmaiiilii, or pilgrim`s hall, in which bending figurines are being fed by women, wearing a distinguishing head-cover, that comes down under the chin. The Gadhwa lintel is discerned by the nonexistence of wholly ornamental elements (no jewellery even is present) and by the dexterous metrical insertion and variety of stances of the procession- work of a superior sculptor `unusually adept in representing three-dimensional poses, with an exceptionally slender canon of proportions`. On stylistic justifications, the lintel would seem to belong to the latter part of the reign of Kumaragupta (C. 414-55), whose inscriptions appear at the place with others of Gupta date. It exemplifies the peak of Gupta narrative relief.

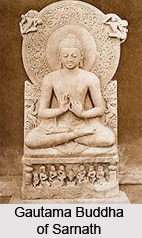

Looking towards images, the Sarnath Buddhas are perhaps the biggest single triumph of the Indian sculptor. They were also the most broadly circularised and persisted to influence Buddha illustrations in eastern India, and far beyond in Southeast Asia, for centuries. By a shot of honest destiny, uncommon in early Indian history, dated examples exist, establishing that they were a comparatively late improvement- not before the 3rd quarter of the 5th century. Nothing seemed to announce these debonaire creations of a virtually inimitable perfection- they exhibited a total break at last, from the plastic concepts of Mathura, and the handling of the human body would hereafter prevail in eastern India.

The Buddhas stand in very trivial dehanchement. They wear the customary lower garment, covered with the sarhghat, specified only by the lines delineating the edges, that body consequently is entirely unveiled, excluding the sexual organs. The large, brilliantly adorned haloes intimately tally with the contemporary Mathura standing Buddhas; the faces on the other hand are  those of beings who have surpassed the world of samsara and exist in a state of complete devout consciousness- a quality, which describes the complete image. Perfectly balanced, the bodies are not realistically treated, but accomplish an approximately marvellous harmony of interflowing planes. They are among the world`s greatest classic accomplishments- classic both in being, consequently unmatchable and in historical sense, in deciding the form, which the Buddha image was to take for centuries.

those of beings who have surpassed the world of samsara and exist in a state of complete devout consciousness- a quality, which describes the complete image. Perfectly balanced, the bodies are not realistically treated, but accomplish an approximately marvellous harmony of interflowing planes. They are among the world`s greatest classic accomplishments- classic both in being, consequently unmatchable and in historical sense, in deciding the form, which the Buddha image was to take for centuries.

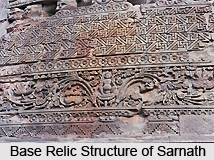

In the greater part of the Sarnath Buddha, Sakyamuni is depicted seated, his hands in the mudra of dharmacakrapravartaa, `setting the wheel of law in motion`, i.e. preaching the First Sermon in Deer Park, Sarnath- an exceedingly apt theme. On the bases, the deer looks at a chakra. Most of the Bodhisattva images are from a later period, but one or two have managed to outlive from this period. Sarnath also had created narrative sculptures of a lofty order, depicting events from Buddha`s life. In the elevated Gupta style, they however have a somewhat quality compared, for example, to the Gadhwa lintel- maybe on account of the conventional subject matter.