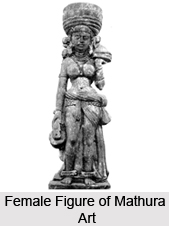

Sculptural works in Mathura was already in an elevated position, with the thriving kingdom of the Guptas. The place was considered sophisticated, classical and developed with the elite residing there, with abundance of scholarly events in all spheres of life, including art, architecture, writing etc. Buddhist sculptures in Mathura tried to represent the religious aspects of faiths like Jainism, Brahmanism and of course Buddhism. The Mathura art forms, illustrating Buddhist sculpture, is however known to have been influenced by the early Indian art forms of Bharhut and Sanchi. The Gandhara art influence cannot also denied in this respect. Mathura based sculptural works are believed to have incorporated the various aspects of the old folk forms of Yaksha worship and thus paved the way to an enhanced and religious stylisation. The phenomenal Buddha sculptures, portraying a forward stance, are known to be among the best showcases, representing the skilled craftsmanship of the sculptors of Mathura. The archetypal characteristics evidencing the Mathura theme comprise the mannish built, broad shoulders, and rising of the right hand, suggests the abhyamudra. At its helm, Mathura School of Art was highlighted by penetratingly courteous features and streamlined body with refined impression through crystalline garbs, including a dissimilar hairstyle.

Sculptural works in Mathura was already in an elevated position, with the thriving kingdom of the Guptas. The place was considered sophisticated, classical and developed with the elite residing there, with abundance of scholarly events in all spheres of life, including art, architecture, writing etc. Buddhist sculptures in Mathura tried to represent the religious aspects of faiths like Jainism, Brahmanism and of course Buddhism. The Mathura art forms, illustrating Buddhist sculpture, is however known to have been influenced by the early Indian art forms of Bharhut and Sanchi. The Gandhara art influence cannot also denied in this respect. Mathura based sculptural works are believed to have incorporated the various aspects of the old folk forms of Yaksha worship and thus paved the way to an enhanced and religious stylisation. The phenomenal Buddha sculptures, portraying a forward stance, are known to be among the best showcases, representing the skilled craftsmanship of the sculptors of Mathura. The archetypal characteristics evidencing the Mathura theme comprise the mannish built, broad shoulders, and rising of the right hand, suggests the abhyamudra. At its helm, Mathura School of Art was highlighted by penetratingly courteous features and streamlined body with refined impression through crystalline garbs, including a dissimilar hairstyle.

In spite of an obviously incessant output, dated sculptures of the 3rd and 4th centuries were practically non-existent in Mathura as elsewhere. Kubera, with its Late Kubera, or a small standing yaksa face, with beautifies of a later date and a bulged chest, riding on over-rounded shoulders, resonant of Udayagiri, for certain belongs to the 3rd or early 4th centuries. So do also the Jain Tirthankaras, with dates in single or double digits, as well as the one in the State Museum, Lucknow. A seated Buddha with likewise unprocessed lions and conferrers on the foundation wears a Gandhara-styled robe, covering both shoulders. On one of the rings of the halo are the extensively and proportionately spaced rosettes, distinctive of the forthcoming century.

During the 5th century. Most seated Mathura images were Tirthankaras. Bases had become much lower in proportion to width and complete with the lions, couchant in posture, their heads facing either the viewer or their own tails.In the centre was a chakra or other religious symbol with kneeling believers on both sides, normally two, their hands in anjali, palms constricted together and held in front of the chest in a signal of greeting intimately, corresponding to the Christian position of the hands in prayer. The solitary Gupta image of a seated Tirthankara, regrettably headless, is dated in the 3rd year of Kumaragupta (422-33). Many figurines were circular in shape. The figure appeared alongside the throne back or simply was edged by ciimara (fly-whisk) carriers, generally raised above the level of the throne.

They had a rather bisexual, broad-hipped and high-waisted look, and the crossed legs seemed to be twisted downward. Faces accompanied the somewhat hard expressions existing for Buddhas, as well as in 5th century Mathura.

They had a rather bisexual, broad-hipped and high-waisted look, and the crossed legs seemed to be twisted downward. Faces accompanied the somewhat hard expressions existing for Buddhas, as well as in 5th century Mathura.

The most extraordinary accomplishment of the Gupta sculptors in Mathura are the standing Buddhas, though most are not quite moving in appeal, owing to a definite tautness. The biggest outlasting absolute example, in the Mathura Museum, is 7ft. (over 2m.) in height; the supreme is now kept in the President`s Palace. The buffalo, however, has overturned itself, as has the goddess, who now stands in the archer`s iitiha posture, her right foot on the buffalo`s head to specify her supremacy. This is the type of which had prevailed hereafter.

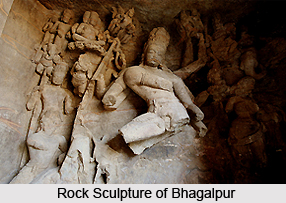

The enormous boar panel, measuring almost 22ft. x 14ft. (7 x 4m.), is one of the biggest and the earliest of the immense high-relief scenes, portraying a godly event of mythological or cosmic consequence. Vishnu, incarnated as the boar with a man`s head, is exhibited raising goddess Earth, Bhu Devi, from the primordial waters- one of the most admired myths of manifestation. She is shown supporting against his shoulder, left knee bent, he paces forward and upward in a triumphant posture of conquest. Nagas worship him from the waters. What is more, here at Udayagiri, the myth is exaggerated more than the usual. In low relief on either sides of the focal figure, arises row upon row of sages and ethereal beings, surmounted by a cluster of gods. The lower part of the ground of this Udayagiri (Vidisa) Cave 5, has an incarnation of Vishnu in his Varaha embodiment, belonging to early 5th century, now kept in New Delhi. They stand with a hardly noticeable flexion, the left hand, and palm outward, the right hand, absent in every case, was apparently raised in the `do not fear` signal. Opposing the Sarnath practice, the pleats of the plates of the samgahti are string-like ridges, a resonance of Gandhara architecture, leaving one or two exclusions, they are wrapped unevenly across the chest also. The brilliant haloes comprise concentric bands of immense beauty and `variety`, the outer one usually beautified with the crenels inherited from the early Kusana Buddhas, the second a tube like band, exemplifying a wreath, with episodic rosettes, succeeded by wider bands of the handsome tangentially cut Gupta foliation. In the centre, a multi-petalled lotus beams from the head.

The discovery of a figurine of similar manner, dated 4358, corroborates the view that these Buddhas forgo those in Sarnath.

The discovery of a figurine of similar manner, dated 4358, corroborates the view that these Buddhas forgo those in Sarnath.

The premium Hindu sculpture of the Gupta era, from Mathura, known till now, is a Vishnu, regrettably without legs or lower arms. The others, far less mighty Vishnu images from Mathura are all likewise disfigured. The face could be Buddha`s, but the Herculean chest and shoulders are not those of an ascetic`s. The armbands correspond to those at Udayagiri, but the rest of God`s jewellery, especially the crown, despite their ornamental enthusiasm, requires distinctness, compared to the best early Gupta works. As a matter of fact, they are no more beautifies worn by real people, but they have transformed into a purely sculptural expression- ornamentation of a statue and not of a living god. There are some outstanding Gupta mukhaliizgas (lingas with one or more emerging heads), in museums and collections and in situ in temples at Mathura, and an exquisite Shiva head from a linga subsists detached in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.