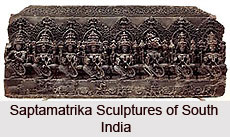

Sapta Matrika is said to be the energies or Shaktis of the deities of the Hindu pantheon like Brahma, Mahesvara, Kumara, Vishnu, Varaha, Indra and Yama. The Saptamatrikas (seven mothers) was a very important religious group in India, especially in South India. Hence, they were called Brahmani, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda.

Sapta Matrika is said to be the energies or Shaktis of the deities of the Hindu pantheon like Brahma, Mahesvara, Kumara, Vishnu, Varaha, Indra and Yama. The Saptamatrikas (seven mothers) was a very important religious group in India, especially in South India. Hence, they were called Brahmani, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda.

Some of the sculptures of Saptamatrikas can be seen adorned in the walls and some are seen in actual worship form. All these goddesses are sculpted according to the codes of the Agamas.

Mythology behind Saptamatrikas

According to the ancient text of architecture and iconography, it is said that the Saptamatrikas should be surrounded by Virabhadra and Lord Ganesha on the left and right respectively. They are seen in this way in most of the temples of South India. The exact iconographic features of the Saptamatrikas can be found in several ancient texts. The temples follow the description of the sculptures found in one or the other of these texts faithfully.

The Kailasanatha temple in Kanchipuram of Tamil Nadu is considered as one of the oldest depictions of the Saptamatrikas. It was constructed during the Pallava age by Narasimha Varman II, better known as Rajasimha Pallava (691-728 A.D.). These Saptamatrika sculptures can be seen in most of the Chola temples in Tamil Nadu and other parts of South India also.

Development of Saptamatrika sculptures

The sequence of development in the sculptures of Saptamatrikas can be traced from Gupta period (3rd to 6th century A.D.), Gurjara Pratiharas (8th to 10th century A. D.), Chandellas (9th to 12th century A.D.), Chalukyas (11th to 13th century A.D.), Pallavas and Cholas (7th to 9th century A.D.). Sculptures of mother goddesses exhibit aesthetic maturity and divine charm. A sculpture of the Gandhara period is found to represent Matrikas with Ganesha. During the Gupta period, Matrikas were carved with stunning elegance. An example of Matrika Kaumari of this period is known to originate in Samalaji, Gujarat. A distinctive curly hair dress is a notable feature of this rhythmic sculpture. During the Gupta Period, the faces are more ovalish and mature. The modeling of the body was more slender and the draperies were more transparent. The upper eyelids that make the eyes look lotus-shaped.

The evidence of Matrika sculptures is further pronounced in the Gurjara - Patiharas and Chandella period (8th to 12th century). Some of the finest sculptures of Matrikas, found in Mahadeva, Devi Jagadamba, Chitragupta Vamana Temples, etc., belong to this period. The quality of sculpting them saw a decline. The depth and thoughtfulness were missing. The emphasis was more on attributes than on artistic sensibility.

The evidence of Matrika sculptures is further pronounced in the Gurjara - Patiharas and Chandella period (8th to 12th century). Some of the finest sculptures of Matrikas, found in Mahadeva, Devi Jagadamba, Chitragupta Vamana Temples, etc., belong to this period. The quality of sculpting them saw a decline. The depth and thoughtfulness were missing. The emphasis was more on attributes than on artistic sensibility.

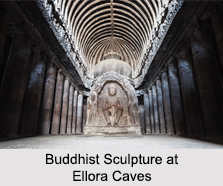

During the rule of the Chalukyas, all Matrikas continued to figure among the deity sculptures of this period. The matted hair dress, piled above the Head and elaborate ornamentation are some features of this period. The Matrikas were associated with Shiva. This is evident in Sapta Matrika flanked by Shiva and Ganesha at the Rameshwara cave, Ellora, a cave dedicated to Shiva.

The period of Pallavas, Cholas, and Pandyas (7th to 13th century) influenced the Sapta Matrika sculptures. The form is slender and elongated with sharp facial impressions. The emphasis on attire was minimal. The tall mukuta adds to the height. The broad armlets are typical of the Chola period.

In some places, the goddesses are each provided with a child, which is placed either on the lap or is standing beside. The sculptures radiate reverence though the associated symbolism and attributes are retained. These sculptures were guided by their patrons. However, Chamunda is always depicted as ferocious and Varahi has a boar`s face.