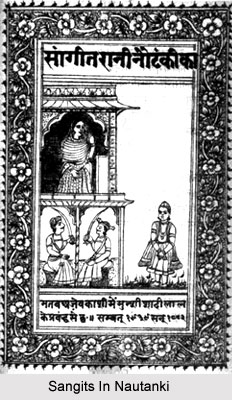

Sangits in Nautanki are referred to the scripts of Swang and Nautanki, or more accurately librettos. This label or the abbreviation is almost invariably part of title. The origin of the word is disputed: it may be an adjectival form of the Sanskrit sangita (music) or a compound of `sang` (mime, drama) and `git` (song). In any case, the term distinguishes this class of texts as intended for musical performance, in contrast to poems or tales meant for silent reading or unaccompanied recitation.

Sangits in Nautanki are referred to the scripts of Swang and Nautanki, or more accurately librettos. This label or the abbreviation is almost invariably part of title. The origin of the word is disputed: it may be an adjectival form of the Sanskrit sangita (music) or a compound of `sang` (mime, drama) and `git` (song). In any case, the term distinguishes this class of texts as intended for musical performance, in contrast to poems or tales meant for silent reading or unaccompanied recitation.

Sangit manuscripts and booklets are probably as old as the theatre itself. Before the printing press came to India, handwritten scripts were circulated among communities of actors to help them memorize parts; they were sometimes collected by patrons. Lithography made possible their duplication and publication, and it is in this form that they were preserved in the nineteenth-century collections of the libraries in London. In the year 1880s, with the introduction of inexpensive Devanagari Printing, the Sangit entered the era of mass communication and became widely printed and reprinted, bought and sold.

Nowadays Sangit chapbooks can be purchased from pavement sellers specializing in popular literature. The vendor who deals in Nautanki Sangits is likely to stock a variety of other items: collections of bhajans (hymns), vratkathds (women`s religious narratives for fasting days), astrological almanacs, folk poems on martial legends like the Alha, traditional joke books (like Ghagh-bhaddari), lokgit anthologies (women`s songs, marriage songs), how-to guides, cheap editions of Hindu devotional texts (Ramcharitmanas, Bhagavad Gita, Hanuman Chalisa), discourses by spiritual masters, film magazines, romances and paperback novels, and detective stories; all are in Hindi.

Among the popular publishing houses, the most prolific publisher of Sangits is Shyam Press in Hathras. Other popular publishers include Dehati Pustak Bhandar (Delhi), Shrikrishna Pustakalay (Kanpur), Babu Baijnath Prasad (Varanasi), and Bombay Pustakalay (Allahabad).

With samples of texts from every decade of the last one hundred twenty years, the history of Nautanki as a folk literature lies open for study. Recurring stories, characters, and motifs can be easily identified, formal structures of language and meter can be historically analyzed, and the styles of different authors, schools, and regions can be contrasted. Furthermore, the printed Sangit yields valuable self-contextualizing information. Prefaces by editors may explain how a play came to be published, under what constraints, or with what purposes in mind. Sometimes a poet`s colophon includes descriptions of dramatic troupes, the roles and function of their personnel, and the musical instruments used. Invocations directed at patrons provide information on the circumstances of performance. As a result, although the libretto was originally devised as an actor`s guide, in its published form it is a self-referencing document that supplies important clues to the evolution of the theatre.