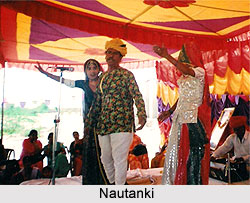

Repertoire of Nautanki comprise of panoply of forms, few of which are known or ever witnessed outside the country`s borders. Those forms characterized by spectacular costumes and brilliant choreography seem to be the ones most frequently transported to Western soil, perhaps because of the commodity value of an image of India as "exotic." For audiences in South Asia, however, there are theatrical traditions in every region and at every level of society, and in all probability theatre has been present during every historical period. Theatre, having many species, has served many purposes. It has provided an arena for the savouring of aesthetic delight by the cognoscenti as expounded in the rasa theory of Sanskrit theatre, and it has served as staging ground for symbolic inversions during rites of reversal such as the Holi festival. It has disseminated moral and religious messages to audiences accessible only by oral pathways of communication, and it has spoken eloquently through the languages of mime, costume, and music.

Repertoire of Nautanki comprise of panoply of forms, few of which are known or ever witnessed outside the country`s borders. Those forms characterized by spectacular costumes and brilliant choreography seem to be the ones most frequently transported to Western soil, perhaps because of the commodity value of an image of India as "exotic." For audiences in South Asia, however, there are theatrical traditions in every region and at every level of society, and in all probability theatre has been present during every historical period. Theatre, having many species, has served many purposes. It has provided an arena for the savouring of aesthetic delight by the cognoscenti as expounded in the rasa theory of Sanskrit theatre, and it has served as staging ground for symbolic inversions during rites of reversal such as the Holi festival. It has disseminated moral and religious messages to audiences accessible only by oral pathways of communication, and it has spoken eloquently through the languages of mime, costume, and music.

Within this variety of forms, Nautanki belongs to the set of theatres whose historical evolution has been quite recent. These theatres rely on spoken vernacular languages that they developed only several hundred years ago. Nautanki employs the languages based on the Khari Boli dialect, a form of speech that probably took linguistic shape during the eighteenth century in the Delhi and Meerut districts. Its written form emerged in the nineteenth century, and it now possesses two literary variants, Hindi and Urdu, the official languages of India and Pakistan respectively (together with English).

The Nautanki theatre of North India is linguistically identified by its use of Hindi and Urdu and its prevalence in the region where these languages are spoken. As a regional form, it is comparable to theatres found in other linguistic territories (largely coinciding in independent India with state borders). These include the Jatra of West Bengal (which employs Bengali language), the Tamasha of Maharashtra (in Marathi language), the Bhavai of Gujarat (in Gujarati language), and others. This is not to say that localized forms of speech never appear in Nautanki performances. Depending on the background of the performers and the audience, dialects may be used. Specific song genres draw on literary dialects such as Braj, Awadhi, and Bhojpuri, and older texts tend to use grammatical endings characteristic of the Braj dialect. However, the predominant medium of Nautanki theatre is Khari Boli Hindi or Urdu.

Nautanki, Jatra, Tamasha and other regional theatres have been shaped by late medieval historical circumstances in each geographical area, and they show marked regional traits beyond language, such as distinctive styles of dress, headgear, ornaments, and makeup, as well as song types, musical instrumentation, dance forms, and gesture language typical of each region. Among themselves, these regional theatres share a number of features: they make extensive use of music and dance, though in somewhat differing ways; their verbal textures are primarily poetic, but they also employ prose, often improvised; their vocabularies of acting, gesture, and costume are stylized; their stage techniques are informal and their productions have sparse props and scenery.

The traditional theatres may be subdivided into those whose dominant ethos is sacred or religious (dharmik) and those whose ethos is secular, a distinction made by practitioners and scholars alike. The secular character of Nautanki is readily observable, for unlike the two religious theatres of the Hindi region, the Ramlila and the Raslila, Nautanki is not oriented toward the praise of particular deities (such as Lord Rama or Lord Krishna), nor are its performances connected to annual religious festivals (e.g. Dashahara or Lord Krishna Janmashtami, common occasions for Ramlila or Raslila performances, respectively).

Nautanki is first and foremost an entertainment medium, and its lively dancing, pulsating drumbeats, and full-throated singing generate an atmosphere considered by many to be opposed to religion and morality. Nor does the theatre draw its characteristic subjects from the pan-Indian religious epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, even in their local forms, as do most traditional theatres including non-sectarian ones such as the Terukkuttu of Tamil Nadu. The social organization of troupes has no connection with religious institutions or priestly groups, and performances are not viewed as in any way auspicious or ritually efficacious.

In the political sense, Nautanki`s secularism is displayed by its almost equal attention to topics identified with Hindu and Muslim cultural traditions. Islamic romances such as Laila Majnun and Shirin Farhad are favourite stories in Nautanki, and one finds many other tales that may have accompanied advancing armies from the Middle East, entered the narrative lore of North Indian Muslims, and then found their way into the theatre. The blend of Urdu and Hindi diction in the texts, together with the inclusion of metrical types from both Hindi and Urdu prosody, also point to a mixed non-sectarian heritage. Muslims and Hindus participate together in the formation of troupes, and Nautanki audiences may be drawn from either or both communities.

Nautanki does address certain semi religious topics drawn from the popular strands of devotion and morality common to Hindus and Muslims. Exemplary stories such as that of King Harishchandra (originally found in the Markandeya Purdna, a Sanskrit compendium of mythology), legends of saints promoting asceticism (Gopichand, Bharathari, Puranmal, and others), tales of self-sacrificing devotees (Prahlad, Dhuruji), and accounts of miracles and magical feats are examples.

As far as is known, Nautanki performances are not and have never been occasions for spirit possession, either on the part of performers or observers. Specific tales included in the Nautanki corpus such as that of Guga, also called Zahar Pir, a saint-deity worshiped by the Chamars (untouchables) in Punjab, are sometimes performed during rituals of possession.