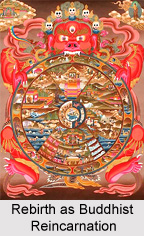

Within Buddhism, the term rebirth or re-becoming (Sanskrit: punarbhava; Pali: punabbhava) is preferred to "reincarnation", as the latter is taken to suggest that there is a determined entity which is reborn. However, this still leaves the question as to what precisely the process of rebirth implies.

Within Buddhism, the term rebirth or re-becoming (Sanskrit: punarbhava; Pali: punabbhava) is preferred to "reincarnation", as the latter is taken to suggest that there is a determined entity which is reborn. However, this still leaves the question as to what precisely the process of rebirth implies.

The lack of a fixed self does not mean lack of continuity. One of the metaphors used to illustrate this is that of fire. For instance, a flame is transferred from one candle to another, or a fire spreads from one field to another. In a similar manner that it depends on the original fire, there is a conditioned relationship between one life and the next; they are not identical but neither are they wholly distinct. The early Buddhist texts make it clear that there is no permanent consciousness that moves from life to life.

Early Buddhists had to deal with the problems of establishing the nature of the causal link between two lives, especially the fundamental one of how one being could receive the fruits of the actions of a previous being, now dead, and how samskaras, or deliberate tendencies to act and think in particular ways can be channelised from one being to another.

The Puggalavada school (now extinct) believed in an individual entity (puggala) separate from the five skandhas that provided a connection of personal continuity that allows for karma to act on an individual over time. The medieval Pali scholar Buddhaghosa stated a `rebirth-linking consciousness` (patisandhi), which connected the arising of a new life with the moment of death. But how one life came to be associated with another was still not made clear. Some schools were led to the conclusion that karma continued to exist in some sense and cling to a particular person until it had worked out its aftermaths. Another school, the Sautrantika, made use of a more poetic model to explain the process of karmic continuity. For them, each act `perfumed` the individual and led to the planting of a `seed` that would later sprout as a good or bad karmic result.

While all Buddhist traditions look to accept some impression of rebirth, there is no united view about exactly how events unfold after the moment of death. Theravada Buddhism mostly maintains that rebirth is immediate. The Tibetan schools, on the other hand, hold to the belief of a bardo (intermediate state) which can last up to forty-nine days, and this has led to the developing of a unequalled `science` of death and rebirth.

While Theravada Buddhism normally denies there is an intermediate state, some early Buddhist texts seem to support it. One school that followed this view was the Sarvastivada, who believed that between death and rebirth there is a kind of limbo in which beings do not yet reap the outcomes of their previous actions, but in which they may yet influence their rebirth. The death process and this intermediate state were considered to offer a uniquely lucky opportunity for spiritual awakening.

There are many references to rebirth in the early Buddhist scriptures. The following are some of the more important: Mahakammavibhanga Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 136); Upali Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 56); Kukkuravatika Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 57); Moliyasivaka Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 36.21); Sankha Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 42.8).

Right concentration

Right concentration (samyak-samadhi o samma-samadhi), as its Pali and Sanskrit name suggests, is the practice of concentration (samadhi). The practitioner will have to focuss on an object of attention until it reaches total concentration and then into the state of meditative absorption (jhana). Traditionally, the practice of samadhi can be developed from mindfulness of breathing, from visual objects (kasina), and repetition of phrases. Samadhi is used to repress the five hindrances in order to enter into jhana. Jhana is an implement used for inculcating wisdom by cultivating insight and use it to fathom the true nature of phenomena by direct cognition, which will then lead to breaking up the ruinations, realise the dhamma and self-awakening. During the practice of right concentration, the practitioner will need to look into and verify their right view; in the process right knowledge will arise, followed by right liberation.