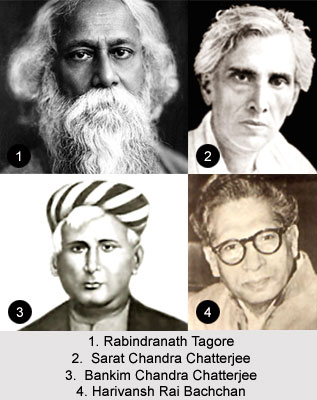

"The heroic sentiment which is the essence of every song and couplet of a Rajasthani is peculiar emotion of its own of which, however, the whole country may be proud" -- Rabindranath Tagore.

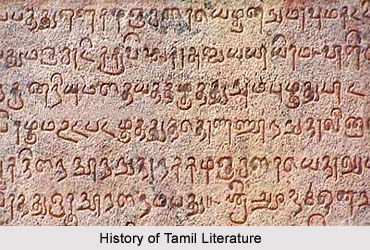

Rajasthani serves as an Indo-Aryan language, bearing its roots in Vedic Sanskrit and Sauraseni Prakrit. The script in which Rajasthani language is employed, is the Devanagari script. Rajasthan is not just about the mysterious wonders of age-old and gargantuan palaces, sky high fortresses, the almost unending desert tracts or the mouth watering cuisines or even the meandering by-lanes, transferring one as if to the bygone era, but also assimilates a fund of folk literature consisting of ballads, songs, proverbs, folk tales and panegyrics. Rajasthani language owns an astounding treasure of literature that was penned in various genres, commencing from 1000 A.D. In the past, the language spoken in Rajasthan was looked at as an accent of western Hindi (Kellogg, 1873). However, George Abraham Grierson (1908) was the first scholar who had lent the nomenclature `Rajasthani` to the language, which was acknowledged through its umpteen dialects in ancient times. In present times however, the National Academy of Letters and University Grants Commission, recognises it as a distinct language from amongst the regional languages of India. Rajasthani is also taught in the Universities of Jodhpur and Udaipur. The Rajasthan Board of Secondary Education had incorporated Rajasthani within the curriculum of studies and it has served as an optional subject since 1973. Beginning from 1947, various language and literature movements have been going on in Rajasthan to earn the status of due recognition. The Rajasthan Government also has distinguished and accepted it as a state language.

Rajasthani serves as an Indo-Aryan language, bearing its roots in Vedic Sanskrit and Sauraseni Prakrit. The script in which Rajasthani language is employed, is the Devanagari script. Rajasthan is not just about the mysterious wonders of age-old and gargantuan palaces, sky high fortresses, the almost unending desert tracts or the mouth watering cuisines or even the meandering by-lanes, transferring one as if to the bygone era, but also assimilates a fund of folk literature consisting of ballads, songs, proverbs, folk tales and panegyrics. Rajasthani language owns an astounding treasure of literature that was penned in various genres, commencing from 1000 A.D. In the past, the language spoken in Rajasthan was looked at as an accent of western Hindi (Kellogg, 1873). However, George Abraham Grierson (1908) was the first scholar who had lent the nomenclature `Rajasthani` to the language, which was acknowledged through its umpteen dialects in ancient times. In present times however, the National Academy of Letters and University Grants Commission, recognises it as a distinct language from amongst the regional languages of India. Rajasthani is also taught in the Universities of Jodhpur and Udaipur. The Rajasthan Board of Secondary Education had incorporated Rajasthani within the curriculum of studies and it has served as an optional subject since 1973. Beginning from 1947, various language and literature movements have been going on in Rajasthan to earn the status of due recognition. The Rajasthan Government also has distinguished and accepted it as a state language.

The development of Rajasthani literature from the bardic language, `Dingal` and virkavya (heroic poetry) took form in the context of the medieval social and political establishments and shapings in Rajasthan. For centuries, Caran bards, court poets and chroniclers have added incessantly to the tradition of Dingal virkavya. In contemporary times even, medieval virkavya as well as still-surviving oral traditions continue to inspire and invigorate Rajasthani prose and poetry. The maturation and growth of written and oral Rajasthani narrative literature can be exemplified by a revision of the medieval and modern tradition of the adventures of Pabuji Dhandhal Rathaur, a 14th century Rajput gallant. Epic poems and eulogistic couplets consecrated to Pabuji formed an integral part of the Dingal manuscript tradition from the beginning of the 16th century. The Caran bards had immortalised his self-sacrifice on the battleground in verses like Pabuji ra duha, Pabuji rau chand and Pabuji ko yash varnan. The oral merits and virtues of the bardic tradition were held back long after the verses became an essential ingredient of the manuscript tradition of the locale.

During the pre-Independence scenario, poets in Rajasthani literature had resurrected the Dingal virkavya to vent out and publicise their anti-British sentiments. Thus, Mahakavi Moraji Ashiya tremendously lauds Pabuji`s unselfishness in Pabu Prakash (1932), a Dingal poem emoting incandescent patriotic pathos. After Independence, the Rajput ideals of virkavya testified to well suit to conveying a nationalist love for the nascent nation. The heart-rending unselfishness of Rajput warriors on the battlefield (referring to these heroic warriors as tyagi in Rajasthani idiom), for example, were smoothly translated into a yearning to give one`s life to the motherland. Poets had also eulogised medieval Rajput gallants and the intimidating freedom fighters in literature in the Rajasthani dialect, utilising Dingal versifications and bardic idiom.

Rajput Tyagi is equally an element of modern, regional definitions of Rajasthani literary identity. Oral narratives also serve as a basis of inspiration for Rajasthani prose writers like Vijay Dan Detha (1927). Vijay Dan Detha is graded amongst Rajasthani pragatishil and pragativad or progressive prose writers, who convey a modern political, often `reformist awareness` through their compositions. The interrelated evolvement of written and oral narratives in Rajasthani literature is worth bearing in mind, when researchers tend to draw a new literary map of the subcontinent. And this perhaps can only be grasped and assimilated when one looks deep within the framework of the history of Rajasthani literature and its gradual development that has moved towards glittering maturity from the Rajputana era to present day patronages.