Introduction

Raagas is considered as of the melodic modes used in Indian classical music. Raagas, as comprehended today, is a melodic notion or idea using five notes of the octave in a specific order. The combination of notes form a scale conforming to precise rules of ascent (aroha), with determined resting places, distinct phrasal movements all of which go to evoke the Raaga`s emotive content. Each Raaga obtains its characteristic mood through the dexterous use of specific principal notes. During raaga elaboration and development, stress invariably falls on the vadi swara, because it is that which helps one to recognize the characteristic movement of the raaga. It is the note towards which the performer returns recurrently and makes it as evidently attractive as possible. The samvadi or the consonant is secondary to the vadi, serving to intensify its effect by complementing it. The samvadi is normally positioned in the next tetrachord, generally the 4th or 5th note above the vadi. It sustains the impression created by the vadi in its own tetrachord.

Pitches in Raagas

In many Hindustani Ragaas, the idea of scales remains alien. This is because it is not so much an abstract scale as a melodic shape which accounts for the distinction between one raga and another. Thus, for instance, though Sa, Ga, Ma, Dha, and Ni are the pitches of Rag Malkosh, it would be wrong to present them as a scale in Malkosh, as those pitches in that succession are not characteristic of Malkosh. Also, the pitches that are being used are most important in distinguishing a particular raga. Continuing with the aforementioned instance, if any pitch other than Sa, Ga, Ma, Dha, and Ni were to be used for melody in Rag Malkosh, the raga will no longer remain Rag Malkosh. It may be mentioned here that a slight retraction is seen sometimes. The most learned artists can sometimes subtly infuse a foreign pitch in some ragas, and this is done in a purposeful way. Also, in some types of melodic figures, "foreign pitches" or an otherwise avoided succession of pitches are considered permissible. This course of retraction emphasizes an important feature about Hindustani Classical Music. It indicates the flexibility of the melodic system and the important role of the individual musician. Despite this flexibility however, the rule for the omission of pitches remains firm. If any of the pitches are omitted, the Raaga no longer remains what it is meant to be. Again citing the former example, if either of Sa, Ga, Ma, Dha or Ni were to be omitted from Rag Malkosh, it would no longer be Rag Malkosh.

The use of specific pitches in a raga forms the basis for another important aspect of pitch in Hindustani Raaga- the concept of melodic shape. There are many Hindustani Raagas which are closer to tune than to scale and are hence said to be more `shapely.` In many of the tuneful Raagas, the context in which pitches occur, and not just which of the pitches occurs is the raaga itself. One of the reasons for which these tuneful Raagas might have developed is that according to tradition, of the seven basic pitches, only one form can be used in context.

A distinguishing feature of a particular raaga is the lower intonation of specific pitches. In those particular ragas where intonation is a special feature, the musician draws attention to particular pitches by either flatting or sharpening a pitch. More often, he uses vibrato to produce a pitch which ranges from being slightly above to slightly below the usual pitch. It is for these feature that the term `Sruti` is employed by some musicians.

Hierarchy of Pitches

The hierarchy of pitches in Hindustani Raaga is a matter of pitch function. Functions that are considered important make the pitches fulfilling them important. The theory of Hindustani Classical Music has undergone a change and the terminology shows it. In the older melodic theory, the most important functions were beginning (graham), ending (nyasa) and predominant (amsa). Over the course of time, the beginning pitches seem to have become relatively unimportant and the ending pitches are no longer designated as such. An important factor in determining some melodies is pitch register. For instance, Chandrakant melodies usually move in the low and middle saptaks. A Raaga is often distinguished by means of the way in which specific pitches are treated, i.e., whether they are connected or ornamented with additional pitches.

In Hindustani music it is not uncommon to see more than one raaga having the same set of notes, yet their vadi and samvadi will differ. For instance, Bhoopali, Deshkar and Shuddh Kalyan share the same pentatonic scale Sa Re Ga Pa Dha, but are differentiated on the basis of their differing vadis and samvadis; similarly, with allied raagas like Marwa, Poorya Dhanashri, Poorya and Shree. While elaborating closely related raagas, the performer brings out the differences in mood and impact by emphasizing certain notes and thoroughly avoiding others. The tonal accents too may vary in the case of raagas having the same aroha and avaroha. Many a time, there exist only hairbreadth distinctions between one tonal accent and another and the risk of `spilling over` into another raaga scale is something skilled performers learn to avoid instinctively. Just as the timbre and tone of voice helps one to differentiate between a request and a command, so the task of a melodic progression, its repeated glidings, waftings towards a tonal centre, would determine its identity.

The personality of a raaga, or the raagabhaava, that shines forth in the art of skilled performers is a fluid and flexible one. Just as no two sculptors can sculpt the same bust alike, so, no two performers can render the same raaga identically.

Classification of Raagas in Hindustani music

Classification of Raagas in Hindustani music is important due to the great diversity of this musical style. The classificatory approach to life has been widely applied in the Hindu tradition. Classification as such seems to have been primarily a concern of Hindu rather than Muslim culture in India. After the arrival of the peoples of Islamic faith in India, music making gradually became largely a Muslim sphere in North India. It remained a Hindu sphere in South India. Classification was pursued hotly in South India, but was practically ignored in the North until this century. The most recently adopted means of classifying Hindustani raagas is by scale type- called `that` in the North.

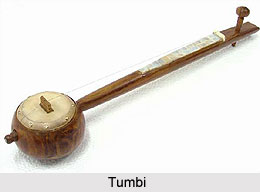

The `that` system is based on musical practice. That is, it was devised as a means of organizing existing raagas into groups with basically the same pitch selection. Bhatkhande suggested ten thats. These ten thats are the basic tunings for a Hindustani stringed instrument with movable frets, the sitar.

They are scale types, not raagas. The ten thats are given below:

| 1 | Kalyan | Sa | Re | Ga | Mai | Pa | Dha | Ni | Sa | |

| 2 | Bilaval | Sa | Re | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dha | Ni | Sa | |

| 3 | Khamaj | Sa | Re | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dha | Ni | Sa | |

| 4 | Bhairav | Sa | Re | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dha;, | Ni | Sa | |

| 5 | Purvi | Sa | Re | Ga | MaS | Pa | Dhal | Ni | Sa | |

| 6 | Marva | Sa | Re | Ga | Mai | Pa | Dha | Ni | Sa | |

| 7 | Kafl | Sa | Re | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dha | Ni, | Sa | |

| 8 | Asavari | Sa | Re | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dha, | Ni, | Sa | |

| 9 | Bhairavi | Sa | ReS | Ga | Ma | Pa | Dhai | Ni | Sa | |

| 10 | Todi | Sa | Re, | Gai | MaS | Pa | Dhai | Ni | Sa |

For each that there is also a raaga of the same name. But the raaga also involves a group of characteristics, like pitch hierarchy, ascent-descent form, characteristic melodic motion or ornamentation, and the like.

However, it may be mentioned here that there are certain difficulties with the system of Bhatkhande`s classification. One of the difficulties of Bhatkhande`s that system is that he did not explain thoroughly his reasons for classifying certain raagas together. For example, Raag Komal Re Asavari, strictly speaking, includes the pitches of Bhairavi that, but it is not classified as such because of other of its characteristics, which are very close to those of Rag Asavari. Raag Malkosh, on the other hand, has the pitches of both Bhairavi and Asavari that but by tradition it is classified as belonging to Bhairavi that. Another difficulty with the Bhatkhande that system is that there are not enough thats to include the variety of scale types that currently appear in raagas.

To counter this, musicologist Nazir Jairazbhoy has suggested effective extension of the system to 32 thats. But however many scale types there could be, other factors seem as important, if not more so, in Hindustani raaga. A wholly successful means of classification has not yet been achieved.