About Shaivism

Shaivism is the branch of Hinduism that worships Lord Shiva as the supreme deity. It is one of the major branches of Hinduism. Shaivism is a very deep, devotional and mystical denomination of Hinduism. It is considered the oldest of the Hindu denominations, with a long lineage of sages and saints who have outlaid practices and paths aimed at self-realization and the ultimate goal of Moksha, liberation.

Shaivism is the branch of Hinduism that worships Lord Shiva as the supreme deity. It is one of the major branches of Hinduism. Shaivism is a very deep, devotional and mystical denomination of Hinduism. It is considered the oldest of the Hindu denominations, with a long lineage of sages and saints who have outlaid practices and paths aimed at self-realization and the ultimate goal of Moksha, liberation.

The followers of Shaivism are called "Shaivas" or "Shaivites". They believe that Lord Shiva is the ultimate being and supreme God. According to the followers of Shaivism, Lord Shiva is the creator, destroyer, preserver, concealer and revealer. It is one of the oldest and one of the four major sects in Hinduism.

Beliefs and Practices in Shaivism

Shaivism encompasses philosophical systems, devotional rituals, legends, mysticism and varied yogic practices. It has both monistic and dualistic traditions. Shaivites believe God transcends form, and devotees often worship Shiva in the form of a lingam, symbolizing the whole universe.

Sects of Shaivism

Sects of Shaivism

Major theological Schools of Shaivism include Kashmir Shaivism, Shaiva Siddhanta and Veerashaivism. While they all acknowledge Lord Siva as the Supreme Deity, they differ from one another in respect of other details such as the modes of worship, nature of Brahman, the nature of individual soul, the relationship between the two, the nature of reality and the means to liberation. These schools of Shaivism primarily fall under one of the three schools of Hindu philosophy, namely Advaita (monism), Vishishtadvaita (qualified monism) and Dvaita (dualism).

Spread of Shaivism

The Nayanars of southern India were poet saints who played an instrumental role between 6th and 8th century AD in popularizing the devotional worship of Lord Shiva among the rural people. Through devotional singing and public display of religious fervour, they preached the path of devotion to Shiva as an effective means to spread their message of divine love and surrender to God and inculcate among people the habit of religious worship and ethical living. The Shaiva tradition lists 63 Nayanars. Lakulisa, Vasugupta, Gorakhnath and Basavanna were some of the religious teachers, who played a prominent role in ensuring the continuation of Shaivism as a major religious sect in the Indian subcontinent.

Lord Shiva Temples in India

There are innumerable Shaivite temples and shrines. The 12 Jyotirlinga are among the most esteemed in Shaivism. Varanasi is considered the holiest city of all Hindus, especially Shaivites.

Scriptural Evidence of Shaivism

In the Rig Veda, Rudra is mentioned only in three suktas. He represents the destructive power of nature. He destroys men and animals but in the Rig Veda itself at some places he is described as a benevolent God. People pray to him for having children and being prosperous. In the Atharva Veda, the malignant aspect of Shiva is emphasized. He is called fearful and destroyer. He is described as having dark blue colour and is called the lord of animals. In the Yajur Veda, there are references to Rudra in two suktas i.e. Tryambaka-homa and Satarudriya.

In the Brahmanas, Rudra is called the chief of Gods i.e. Devadhipati, Lord Isana and the Great God Mahadeva. He is also called Bhutapati and is a dread figure who took over the dominion of Prajapati over all cattle. In the Svetasvatara Upanishad, Shiva is called the super God or Parabrahma and it is stated that with his power the Prakrti or Nature becomes active. In the Manavagrhya-sutra he is associated with the cremation ground. In the Apastamba Grhyasutra, Shiva is still classed among the minor Gods. In the Ramayana and the Mahabharata the full development of Shaivism can be seen.

Shaivism in Narada Purana

Lord Shiva as compared to Vishnu is in a lower position. His eulogization is not more significant than that of Vishnu"s. But again Shaivism in Narada Purana has enumerated some characters which have not been done in other puranas.

Lord Shiva as compared to Vishnu is in a lower position. His eulogization is not more significant than that of Vishnu"s. But again Shaivism in Narada Purana has enumerated some characters which have not been done in other puranas.

In the Narada Purana, Lord Shiva is the well-known god. Shiva is his alter ego. He is very kind to his devotees. He fulfils desires of all his worshippers. In sage Gautama hermitage when Parvati criticises Shiva, Lord Vishnu is enraged and tries to cut off her head but Siva controls him. This shows the great regard that Vishnu had for Shiva. Narada has described Sivalinga"s magnitude and its worship.

Narada gives an illustration of the splendour of Shiva while unfolding story of Pundankapura. There is description of Tandava which is performed by Shiva with Uma, Vinayaka, Skanda and others. Among the Siva`s family members, only Lord Ganesha is specifically dealt with. In the Narada Purana there is a description of Ganesha"s worship with chanting of mantras. The epithets of Ganesha mentioned in the Purana are: `Ganesa` i. e. group also `Ganapati`, `Gajasya` `Vinayaka` `Vighnesha` `Vakratunda` and many others. Mahaganapati is described as the rising Sun, source of the existence and destruction of the universe, and so on. Vakratunda is elephant-faced, as bright as the rising Sun, clad in red garment, wearing red ornaments and holding Pasa (noose) and Ankusa (goad) and displaying Abhaya (protection) and Vara (boon). Elsewhere the worship of Vinayaka and Lakshmi is mentioned followed by their wives like Siddhi and Samriddhi.

The Pasupata doctrine described by Narada lays prominence on the observing the practice of Yoga and Bhakti. Narada`s treatment of Pasupata differs from that of other Puranas as it gives an intricate and thought through elucidation.

Shaivism, especially Pasupata, has been given a fuller treatment here than in the other Puranas. Among the Shiva hierarchy of gods, only Ganesha has been placed at same level with Vishnu. Lord Siva also was regarded as an important deity, and the worship of Shivalinga too was prevalent during the period of this Purana.

Shaivism in Different parts of India

Shaivism gradually spread far and wide in different parts of India. With an interesting history and with the copious tradition, Shaivism made its presence felt in South India, Kashmir and in other parts of India.

Shaivism gradually spread far and wide in different parts of India. With an interesting history and with the copious tradition, Shaivism made its presence felt in South India, Kashmir and in other parts of India.

Shaivism in South India

Tirumular"s ``Tirumandarim`` is a highly abstruse work on Shaivism. It elaborates the Shaiva doctrine. The author tried to compare the Agamas or Shaiva canon with the Vedas. According to him ``Becoming Shaiva is the Vedanta Siddhanta. Charya, Kriya, Yoga and Jnana are the four stages in the Sadhana. When the aspirant has reached the last stage, the grace of God descends on him and by that he is released``. The highly sectarian character of Shaivism in South India in the time of Tirumular may be inferred from one of his statements in which he says that "to feed a Shivajani once is more meritorious than to gift of a thousand temples or the feeding of a crore of Brahmins versed in the Veda". He regards the Shiva canon as truly the word of God.

After Mahendra Pallava became a convert to Shaivism, Kochi became a center of Shaivism. This great upsurge in favour of Shaivism was due to devotional poetry that flows from the lips of the Shaiva saints who lived in this age. Appar in the timeframe of A.D. 602-639, Sambandhar or contemporary of Appar, Sundaradramurti and Manik Kavachakam all were inspired saints, who loaded the country with a great wave of devotional poetry and thus created in the minds of men a disposition for the pursuit of spirituality. These Nayanars or Shaiva saints set up Shaivism on a strong foundation in South India.

After Mahendra Pallava became a convert to Shaivism, Kochi became a center of Shaivism. This great upsurge in favour of Shaivism was due to devotional poetry that flows from the lips of the Shaiva saints who lived in this age. Appar in the timeframe of A.D. 602-639, Sambandhar or contemporary of Appar, Sundaradramurti and Manik Kavachakam all were inspired saints, who loaded the country with a great wave of devotional poetry and thus created in the minds of men a disposition for the pursuit of spirituality. These Nayanars or Shaiva saints set up Shaivism on a strong foundation in South India.

Kashmir Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism is one of the most highly developed schools of Indian Philosophy. It developed between the 7th and 12th Centuries of the Christian era. Kashmir Shaivism is not a religion. It is a philosophy open to those who have the desire to understand it; hence, for its study there are no restrictions of caste, creed or colour.

Kashmir Shaivism is one of the most highly developed schools of Indian Philosophy. It developed between the 7th and 12th Centuries of the Christian era. Kashmir Shaivism is not a religion. It is a philosophy open to those who have the desire to understand it; hence, for its study there are no restrictions of caste, creed or colour.

Literary Sources of Kashmir Shaivism

All the important works on this philosophy are written in Sanskrit language. There are a few translations of some minor works on Shaivism available in English. The "Pratyabhijna Vimarsini" of Abhinavagupta, the most important work on the subject, has recently been translated into English and has been published also. But it remains a fact that one cannot still learn much about Shaivism even after studying this rendering. Only a person who can understand the original Vimarsini in Sanskrit can fully understand that translation with the help of the original Sanskrit.

Trika Philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism is also called "Trika Philosophy", the three-fold scene. This threefold science is based on the three Energies of Lord Shiva. These three Energies are;

i. Para (Supreme): Para means the Supreme Energy of Lord Shiva, otherwise known as his Subjective Energy.

ii. Parapara (Intermediate): Parapara is the medium, the Intermediate Energy of Lord Shiva. It is called his Cognitive Energy.

iii. Apara (Inferior): Apara is Lord Shiva"s Inferior Energy and is referred to as his Objective Energy.

Purpose of Trika Philosophy in Kashmir Shaivism

It is believed that the human being resides in the Inferior or Objective Energy of Lord Shiva. As long as one resides in Objective Energy, one is the victim of sadness and sorrow, and is entangled in the wheel of repeated births and deaths. So one has to emerge from Objective Energy and enter into Subjective Energy, in which one is liberated from all this sadness, and becomes absolute in the attainment of final beatitude. This Trika Philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism teaches one how this individual being immersed in Inferior, Objective Energy can be carried towards the Supreme, Subjective Energy of Lord Shiva through his Cognitive, Intermediate Energy. So the purpose of studying this Trika system is to rise from Objective Energy through Cognitive Energy and finally be one with the Subjective Energy of Lord Shiva.

Path of Consciousness in Kashmir Shaivism

In order to achieve this state, there are three means which have been laid down by Trika thought. These means lie within the sphere of Cognitive Energy, for it is Cognitive Energy alone that can carry one towards the Subjective Energy of Lord Shiva. The purpose of Cognitive Energy is to develop the limited being"s capacity and ability to receive God-consciousness. In the body of Cognitive Energy, as has been said, are three means. The first and supreme means is called "Shambhavopaya". The second, intermediate means is called "Shaktopaya" and the third, inferior means is called "Anavopaya". These means are handled and practised according to the ability of the seeker.

Shambhavopaya: Shambhavopaya is that path wherein the individual has to do away with all the various long-winded procedures such as recitation of Mantras, of Sadhana based on breathing, meditation on particular deities, concentrating on some spiritual thought and so on. One only has to develop his awareness of Consciousness. By the constant awareness of this Consciousness, the individual "I" consciousness fast disappears and it is united with God-consciousness.

Shaktopaya: Shaktopaya is the means in which the aspirant or seeker has to develop concentration upon God-consciousness by means of some particular spiritual thought bestowed by the master. Here the Sadhaka has to concentrate on that particular thought of God-consciousness without the support of Pranayama, Mantra and so on. He must develop God-consciousness simply and only by meditating upon this thought that will carry him to the Supreme State and Transcendental being.

Anavopaya: Anavopaya is that means in which a Sadhaka who is endowed with an inferior capacity of mind and meditation must develop God-consciousness by resorting to meditation. This is done with the practice of Pranayama and the recitation of Mantras. In this third inferior path, a Sadhaka has to develop God-consciousness by seeking the support of the inferior methods like Pranayama that finally carries one to God-consciousness, in the end.

Kashmir Shaivism remained confined within the boundaries of Kashmir. The Punjab and all other frontier regions of India were frequently attacked first by Huns and then by Pathans in those centuries and, therefore, scholars and students could not come to, or go from, Kashmir freely and safely in those times. For this reason, knowledge of this most important school of Indian philosophy got itself confined to the boundaries of the Valley of Kashmir and could not spread in other parts of India. It is on account of this fact that the Shaivism of Kashmir is very little known to scholars outside Kashmir even to this day.

Schools of Kashmir Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism is a school of Philosophy that developed in Kashmir. Also known as the Trika Philosophy, it rests on the three energies of Lord Shiva. The system of Kashmiri Shaivism is based upon Tantras spoken by Lord Shiva. These Tantras are divided into three classes- one class is that of the monistic tantras. They are called Bhairava Tantras; the second group of Tantras is founded on the mono-dualistic aspect of Kashmir Shaivism. These Tantras are called Rudra Tantras; the third class is based on dualistic Shaivism. These Tantras are called Shiva Tantras.

The philosophy of these Tantras was re-originated at the beginning of Kaliyug by Sage Durvasa. Many centuries later this Tantric philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism was taught by the four great Masters in four Great Schools, Paratyabhigna School, Krama School, Kula School and Spanda School.

Paratyabhigna means Recognition. The realisation of what one has always been in one`s essential, timeless nature. This system was expounded in Kashmir by Somananda.

The Krama School is grounded in space, time and form. Its purpose is to develop such strength of awareness that one transcends the circle of time, space and form and thus becomes timeless, space-less and formless. This thought of the Krama School of Shaivism was taught by Shri Erakanatha.

The third school of Kashmir Shaivism is called the Kula system. The purpose of this school is to discard Individual Energy and to enter into blissful energy of the totality. Thisi thought was re-orginated and taught by Sumatinatha in Kashmir.

The fourth, the Spanda School of this system was re-originated in Kashmir by Vasaguptanatha. Spanda means `Vibration` and the system which goes by its name directs the aspirant to concentrate on each and every movement in this world. Even the movement of a blade of grass will carry you to God-consciousness.

These four schools are not too different or separate from each other. All four carry the Sadhaks to the one and that is Universal God-consciousness. This thought of Kashmir Shaivism is so great, world-affirming and Universal that it has deeply impressed many western minds too, holding out as it does the wonderful vision of this whole Universe as nothing but the Blissful energy of an all pervading consciousness, Lord Shiva.

Pasupata Shaivism

Within the higher path (ati marga) two important orders existed, the Pasupata and a sub-branch, the Lakula, part of which was the Kalamukha order. The Pasupatas are the oldest Shaiva sect, probably from the second century CE, referred to in the Naraniya section of the Mahabharata. The only Pasupata scripture is Pasupata Sutra with a commentary by Kaundinya. According to tradition, this text is the revelation of Rudra who became the possibly historical sage, Lakulisa, by entering and reanimating the corpse of a Brahman in a cremation ground. This form is also regarded as the last of Shiva`s incarnations mentioned in the Kurma Purana. In this form he gave out the teachings contained in the Pasupata Sutra.

Within the higher path (ati marga) two important orders existed, the Pasupata and a sub-branch, the Lakula, part of which was the Kalamukha order. The Pasupatas are the oldest Shaiva sect, probably from the second century CE, referred to in the Naraniya section of the Mahabharata. The only Pasupata scripture is Pasupata Sutra with a commentary by Kaundinya. According to tradition, this text is the revelation of Rudra who became the possibly historical sage, Lakulisa, by entering and reanimating the corpse of a Brahman in a cremation ground. This form is also regarded as the last of Shiva`s incarnations mentioned in the Kurma Purana. In this form he gave out the teachings contained in the Pasupata Sutra.

The Pasupata ascetic had to be a Brahman male, who had undergone the high-caste initiation ceremony. Although he could become a Pasupata from any stage of life, his high-caste status was still important in his religious practice in so far as he should not speak with low castes nor with women. Indeed one passage of Kaundinya`s commentary on the Pasupata Sutra speaks in misogynistic terms of women as the temptresses of the ascetic, who creates madness in him, and whose sexuality cannot be controlled by scripture. The Pasupata ascetic had to be a Brahman and had to be celibate (brahmacharya), though he was nevertheless disapproved of and rebuked by some Vedic, Smarta texts such as the Kurma-Purana.

The Pasupatas seem to have been very much on the edges of orthodox householder society, going beyond the four stages to a fifth, `perfected stage` and spurning Vedic householder injunctions on purity and family life. Yet, unlike many other Shaiva groups, the Pasupata never completely abandoned or explicitly rejected Vedic values, wishing to see his tradition as in some sense the culmination and fulfillment of Vedic life rather than its rejection. Liberation from karma and rebirth occurred at death: a liberation which was conceptualized as acquiring the qualities of omniscience and omnipotence. Although ultimately this liberation was through the grace of Rudra, some effort on the part of the Pasupata was needed. This took the form of a vow or observance (vrata) which involved a spiritual practice (sadhana) in three developmental stages.

Among the three stages that are to be followed, the first involved the ascetic living by a Shaiva temple, covering himself in ashes while avoiding bathing in water, and worshipping the deity through dancing and singing, meditation on five mantras sacred to Lord Shiva, laughter and temple circumambulation. The second stage was to leave the temple, remove external signs of his cultic affiliation, and behave in public places in anti-social ways such as acting as if deranged, snoring loudly while not being asleep, and even acting as if crippled. This behaviour was to invite the abuse of passers-by in order that their merit or good karma would be transferred to the ascetic, while his bad karma would be transferred to those who had abused him. The third and final stage was to withdraw to a remote place, such as a cave or deserted house, in order to meditate upon the five sacred mantras and on the syllable `om`. When this meditation could be achieved effortlessly, he finally withdrew to a cremation ground where he lived from whatever he could find and ultimately died gaining union with Rudra.

Apart from these, there were various sub-divisions among the Pasupatas, the most important of which was the Lakula. These were ascetics who accepted the doctrines of the Pasupata Sutra, though they were more extreme in their ascetic practices and rejection or transcendence of Vedic injunctions than the other Pasupatas. Part of the Lakula order were the Kalamukhas who flourished from the ninth to thirteenth centuries and about whom the information is gained mainly from south Indian epigraphic evidence. They were prevalent in Karnataka where they were superseded by the Lingayat sect in the thirteenth century. The Kalamukhas had their own temples and, in spite of strongly heterodox elements in their practices, such as worshipping Rudra in a pot filled with alchohol and covering themselves in the ashes of corpses rather than cow-dung, they regarded themselves as being within the Vedic fold.

In contrast to the higher path (ati marga) which was thought to lead straight to liberation, the path of mantras (mantra marga) leads to liberation via the acquisition of magical powers and experiencing pleasure in higher worlds for initiates. Within this general category are a number of traditions and ritual systems can be divided into two broad categories, the Shaiva Siddhanta and non-Siddhanta systems which incorporate a number of other groups and texts. All of these traditions within the path of mantras revered as authoritative revelation a vast body of texts known as the Agamas and Tantras, texts which were regarded as heterodox by the strictly orthodox Vedic tradition. Even so, many of these texts came to infiltrate orthodoxy and came to be revered as authoritative even within Smarta circles. The traditions of the path of mantras are known as the `tantric traditions`, for their revelation comprises the Shaiva tantric texts. Before going on to examine the traditions of the mantra marga, we need first to make some general points about the tantric revelation, the Agamas and Tantras.

In contrast to the higher path (ati marga) which was thought to lead straight to liberation, the path of mantras (mantra marga) leads to liberation via the acquisition of magical powers and experiencing pleasure in higher worlds for initiates. Within this general category are a number of traditions and ritual systems can be divided into two broad categories, the Shaiva Siddhanta and non-Siddhanta systems which incorporate a number of other groups and texts. All of these traditions within the path of mantras revered as authoritative revelation a vast body of texts known as the Agamas and Tantras, texts which were regarded as heterodox by the strictly orthodox Vedic tradition. Even so, many of these texts came to infiltrate orthodoxy and came to be revered as authoritative even within Smarta circles. The traditions of the path of mantras are known as the `tantric traditions`, for their revelation comprises the Shaiva tantric texts. Before going on to examine the traditions of the mantra marga, we need first to make some general points about the tantric revelation, the Agamas and Tantras.

The religious culture of the Tantra is essentially Hindu and the Buddhist tantric material can be shown to have been derived from Shaiva sources. There is a substantial body of Jain Tantras and there was a corpus of Tantras to the Sun (Surya) in the Saura tradition. The tantric texts are regarded as revelation, superior to the Veda, by the traditions which revere them: the Shaiva Tantras are thought to have been revealed by Shiva, the Vaishnava Tantras by Lord Vishnu and the Sakta Tantras by the Goddess, and transmitted to the human world via a series of intermediate sages. Tantric Shaiva groups would regard their revelations as the esoteric culmination of Vedic orthodoxy, while Buddhist Vajrayanists would similarly regard their Tantras as the culmination of Mahayana Buddhism.

The Tantras generally take the form of a dialogue between Shiva and the Goddess (Devi, Parvati, Uma). The Goddess, as the disciple, asks the questions and Shiva, as the master, answers. In the Vaishnava Tantras (i.e. Pancaratra Samhitas) the dialogue is between the Lord (Bhagavan) and the Goddess Sri or Laksmi. In some Tantras focused on the Goddess - those of the Sakta tradition - it is Shiva who does the asking and the Goddess who replies. This narrative structure reflects the importance and centrality of the guru in Tantrism. As the Goddess receives wisdom from Shiva, or in some cases vice versa, so the disciple receives wisdom from his or her master. The meanings of the Tantras are often obscure and it must be remembered that they were compiled within the context of a living, oral tradition and teachings given by the guru. The Tantras often regard themselves as secret, to be revealed by the guru only with the appropriate initiation which wipes away the power of past actions.

Traditionally the Tantras should cover four topics or stand on four `feet` or `supports` (pada), namely doctrine (vidya- or jnana-pada), ritual (kriya-pada), yoga (yoga-pada) and discipline or correct behaviour (carya-pada), though only exceptionally do the texts follow this scheme. While there is divergence over doctrine and each tantric system regards itself as superior to the others, there are nevertheless common elements, particularly in respect of spiritual practice (sadhana) and ritual: practice cuts across doctrinal distinctions.

Although the outer or higher path (ati marga) does have the Pasupata Sutra, it may be the case that it did not have its own distinctive revelation relying, rather, on the scriptures of other traditions while regarding itself as transcending all scriptures. The revelation of the path of mantras (mantra marga), on the other hand, comprises all the Shaiva Tantras; a vast body of texts belonging to a number of groups. The most important distinction with the path of mantras is between the tradition known as the Shaiva Siddhanta on the one hand, and non-Siddhanta groups, or the teachings of Bhairava (Bhairava-sastra), on the other. These are themselves subdivided into a number of traditions. There are twenty-eight Tantras of the Shaiva Siddhanta (divided into ten Shiva Agamas and eighteen Kudra Agamas) and numerous Bhairava Tantras.

Puranic Shaivism

During the Gupta dynasty (c. 3 20-500 CE) puranic religion developed and expanded, and the stories of the Puranas spread rapidly, eventually throughout the subcontinent, through the singers or reciters, and indeed composers, of the narratives. This expansion was accompanied by the development of brahmanical forms of worship, the Smarta or pauranika, based on those texts. With the decline of the Guptas, while this Smarta worship is well established, there occurs an increase of esoteric cults, many of which, or elements of which, become absorbed into brahmanical forms of worship.

The Shaiva Puranas, the most important of which are the Linga, and the Shiva Puranas, contain the usual puranic subjects of genealogies, the duties of different castes, Dharma Sastra material and astrology, as well as exclusively Shaiva elements such as the installing of lingas in temples, descriptions of the various forms of Lord Shiva, and the nature of Shiva, whose body is the cosmos, as transcendent and immanent. Apart from material on the formal worship of Shiva, Puranas such as the Linga also contain information on asceticism and yoga, particularly the yoga of the Pasupatas. The Puranas classify Shaivas into four groups, namely the Pasupata, Lakulisa, Shaiva and Kapalika, while Ramanuja in his commentary on the Brahma-Sutra lists the Shaivas, Pasupatas, Kapalins and Kalamukhas. All these groups are generally outside the Vedic or puranic system. Indeed all the Puranas were composed within the sphere of Vedic or Smarta orthodoxy and texts such as the Kurma-Purana condemn the Pasupata system, favouring instead the authority of the Satarudriya and a late Upanisad containing Shaiva material, the Atharvaiiras Upanisad. Although the Puranas are pervaded by non-orthodox Shaiva material, they nevertheless distance themselves from these non-orthodox or tantric systems which posed a threat to Vedic purity and dharma.

A Brahman householder who worshipped Shiva by performing a puranic puja, making offerings by using Vedic mantras to orthodox forms of Shiva, was not an initiate into a specific Shaiva sect, but worshipped Shiva within the general context of Vedic domestic rites and Smarta adherence to varnasrama-dharma. In his commentary on the Brahma Sutra Sankara refers to Maheshwaras who worship Shiva, probably meaning those who follow the pauranika form of worship. As per some scholars, such a brahmanical Shaiva within the Smarta domain, a Maheshwara, can be contrasted with an initiate, technically known as a Shaiva, who has undergone an initiation (diksha) and who follows the teachings of Shiva (Shivasasana) contained in Shaiva scriptures (sastra). While the Shaiva initiate hoped for liberation (moksa), the Shaiva householder or Maheshwara would at death be taken to Shiva`s heaven (Shiva loka) at the top of the world egg, where vaikuntha would be for the puranic Vaishnava.

The Shaiva initiates (as opposed to the lay, pauranika devotees) can be further classified within a more general distinction, between on the one hand the `Outer Path` (ati marga) and on the other the `Path of Mantras` (mantra marga). These are two main branches described in Shaiva texts, the Agamas or Tantras. The former, open to ascetics only, is a path exclusively for the purpose of salvation from samsara, while the latter, open to ascetics and householders, is a path which leads to eventual salvation, but also to the attainment of supernatural or magical powers (siddhi) and pleasure (bhoga) in higher worlds along the way. The path of the ati marga might also be rendered as the `higher path` - the path which has transcended the orthodox system of four stages of life (asrama), going even higher than the orthodox stage of renunciation according to the Atimargins.

Tantra in Shaivism

The philosophy of tantra in Shaivism has made an enormous impact. Advaita Shaivism is one of the major aspects of Tantra that flourished in the Kashmir Valley which later came to be known as Kashmir Shaivism. The goal of Shaivites is to recognize the true nature as the Shiva, which is the manifestation of consciousness, and then turn to all the creations and see its divinity.

The philosophy of tantra in Shaivism has made an enormous impact. Advaita Shaivism is one of the major aspects of Tantra that flourished in the Kashmir Valley which later came to be known as Kashmir Shaivism. The goal of Shaivites is to recognize the true nature as the Shiva, which is the manifestation of consciousness, and then turn to all the creations and see its divinity.

The ultimate goal of Shaiva Tantra is self-recognition and realizing of one`s own self with Shiva. In Shaivism the Purusha and Prakriti are integrated. Shiva in Shaiva tantra is depicted as Yogeshwara. Lord Shiva had initiated the system of yogic meditation in Tantric practices. The Lord is personified in various names like the `relentless mediator`, `Dakshinamurti`, or the `Mahayogi`. Shiva is the basis of foundation of yogic practices in Tantra who is known to possess the `third eye` and who transcends all three worlds every time. Shiva in Tantric practice is abounding with legends and stories about belittling Brahma, the progenitor of the Universe. The form of Shambhavi, Lord Shiva and Shakti is also an integral part of Shaiva Tantra. Shambhavi when aligned with Lord Shiva and Shakti, it is referred to the Mudra in which the Lord is depicted as sitting in a serene posture with eyes half-open. Shambhavi here stands for uniting the microcosm with the macrocosm by offering every sense to the Goddess Kali.

Divine Shakti functions to reveal the divine glory of the Lord simultaneously as transcendent being and the cosmos. The incessant activity of Shakti is called vibration. Self-recognition is the ultimate goal of Shaiva Tantra. The entire creation is divinized. Shaktipata is an explicit and central concept in Shaiva Tantra. It is said to be transmitted through everything that brings us to the spiritual path and moves us closer to the ultimate goal. However, in the context of Shaivism, it is the grace of God that comes through a guru`s initiation. The Shaivites recognize their true nature as Shiva and then the entire creation to them seems divine.

One of the most significant philosophical expositions which arose from the practice of Kundalini MahaYoga was Tantric Shaivism. Tantric Shaivism was a non-dualistic school of thought that emerged from the inner practice of Kundalini. These practices blossomed from the hearts of many great Tantric masters who are called Mahasiddhas.

Influence of Shaivism on Folk Music in East India

Influence of Shaivism on folk music in East India can be observed in various songs. Shaivism also called "Saivism" is one of the four most widely followed sects of Hinduism. It reveres the god Shiva as the Supreme Being. Shaiva is a religious faith that was widely propagated among the people as a result of Brahmanical bias of the Sena kings of Bengal, though this thought was deeply rooted in the principal religious system from days of yore.

Influence of Shaivism on folk music in East India can be observed in various songs. Shaivism also called "Saivism" is one of the four most widely followed sects of Hinduism. It reveres the god Shiva as the Supreme Being. Shaiva is a religious faith that was widely propagated among the people as a result of Brahmanical bias of the Sena kings of Bengal, though this thought was deeply rooted in the principal religious system from days of yore.

Various streams of Brahmanical thoughts were responsible for the common interpretation of the image of Lord Shiva. Another feature developed around the mythical marriage of Lord Shiva and Parvati, a humanized matrimonial ceremony of gods taking place, as it were, in the hearth and home of a common villager. From this welled up the emotional outburst of rural people centring round the parting of daughter from the house of her parents after marriage (Vijaya Dashami) and reunion after daughter"s return from her husband"s house (Agamani vijaya). Touching music was spontaneously set to sporadic compositions based on this touching events. Some very popular compositions of the same genre have spread in the rural people during the nineteenth century.

Historically, the image of Shiva was very popular from the early period of the Hindu cult. During the predominance of Buddhist faith, Hindu Brahmins also participated in Hinayana Buddhist processions. As a result of their participation, the images of Hindu gods like Shiva, Lord Indra, Lord Brahma, etc., were brought to the forefront of the procession along with the principal image of Buddha. The rulers followed this practice in their act of popularizing Buddhist cult. Then, again, Shiva also had to face depredation due to the pressure from other local cults. When Lord Krishna plays the main role in the race of religious faiths, Shiva falls back, though saiva faith predominates among certain sections of people. In Gopichandergan, a narrative representing Natha cult, mention has been made of Lord Shiva"s escape from an attack by another deity (kacu-bari diya siv palaiya jay).

Historically, the image of Shiva was very popular from the early period of the Hindu cult. During the predominance of Buddhist faith, Hindu Brahmins also participated in Hinayana Buddhist processions. As a result of their participation, the images of Hindu gods like Shiva, Lord Indra, Lord Brahma, etc., were brought to the forefront of the procession along with the principal image of Buddha. The rulers followed this practice in their act of popularizing Buddhist cult. Then, again, Shiva also had to face depredation due to the pressure from other local cults. When Lord Krishna plays the main role in the race of religious faiths, Shiva falls back, though saiva faith predominates among certain sections of people. In Gopichandergan, a narrative representing Natha cult, mention has been made of Lord Shiva"s escape from an attack by another deity (kacu-bari diya siv palaiya jay).

Saiva faith is connected with Sakta religious thought, the two being separate phases of one fundamental religious genre. Though methods differ largely, some Shiva worshippers find their religious faith deployed in a different way in the worship of Sakti, the divine symbol of the mother, a separate manifestation of the same Being. In Bengal, the two phases had unique spontaneous expression in public since the Buddhist days. Believers in Jsakti, mostly rural folks, were connected with the narrative cults of the people starting from the Sena period, while Saivas gave expression to their thoughts in Gambhira and Gajan. Rajataranginl of Kalhana of Jammu and Kashmir refers to the existence of diva temples and performance of Gambhira in the seventh century. Old tradition of Gambhira survives in the Maldah district.

Influence of Shaivism on Odissi Dance

Shaivism as a religion has a continuous history of at least four thousand years. It is well admitted that at one time it was the dominant religion that influenced the culture and civilisation of India. Since pre-historic times, it is believed that Shaivism fostered a tradition of art in accordance of which the temples and images were built and made. Though it is not known when Shaivism had come to India yet there are enough evidences to prove its existences from the 4th century A.D.

Shaivism as a religion has a continuous history of at least four thousand years. It is well admitted that at one time it was the dominant religion that influenced the culture and civilisation of India. Since pre-historic times, it is believed that Shaivism fostered a tradition of art in accordance of which the temples and images were built and made. Though it is not known when Shaivism had come to India yet there are enough evidences to prove its existences from the 4th century A.D.

Evidence of Shaivism Influence in Temples

Satru Bhanja, a king of Bhanja dynasty had built temples for Lord Shiva. The image which is present in the temple is of a dancing Shiva in a nude Urdhalinga form with eight forms. In the uppermost, two hands are engaged in holding a serpent and two other hands are engaged in playing a Veena, one holds a Trisula, one an akshya mala, one a damaru and one is in stretched position in Pataka hasta suggesting release.

During the 6th and 7th centuries while the Bhanja kings were ruling in the high lands of Odisha, the Sailodbhava dynasty rose to power in Kangoda Mandala. The rule of this dynasty beginning from 570 AD continued up to 675 AD for over a period of hundred years. This period is marked as an important one in the history of religious movement in Odisha. Though the Sailodbhava rulers were staunch Shaivites, most of them performed Aswamedha and other sacrifices out of their respect for the Vedic religion. Shiva has been held up as the highest God in all opening lines of all the inscriptions of this dynasty.

The sculptures of the earlier Shiva temples built during the rule of the Sailodbhava dynasty testify the spread of Lakuli sect. The images of Lakuli find a prominent place in the front facades of the temples. In the sculptures Lakuli appears alone or with two or four of his disciples seated on the lotuses rising from a common lotus forming the pedestal of their master.

The sculptures of the earlier Shiva temples built during the rule of the Sailodbhava dynasty testify the spread of Lakuli sect. The images of Lakuli find a prominent place in the front facades of the temples. In the sculptures Lakuli appears alone or with two or four of his disciples seated on the lotuses rising from a common lotus forming the pedestal of their master.

In the Shaiva form of dance, the devotee is enjoined to dance and sing standing to the south of the image with face turned towards the north. He is also enjoined to act as a lover at a public place.

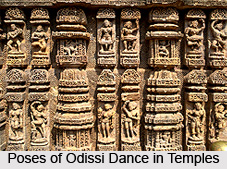

The early temples of Bhubaneshwar closely reflect the Shaiva form of dance and art. Four early Shiva temples of Bhubaneshwar namely Bharateshwar, Laxamaneswar, Satrugheneswar and Parasurameswar deserve special mention. All these temples are ascribed to the 6th and 7th century AD. These temples were built by the Sailodbhava rulers. Besides the Nataraja images, there are also appearances of dancing girls in a number of superb panels of the highest workmanship that are evidently the sculptural equivalents of the greatest phases of dancing of that time.

Another important piece of sculpture giving the prevalence of the predominant dance form in Odisha has been depicted in the Kapileswara Temple at Bhubaneshwar.

Other Aspects found in Temples

The ornaments that are generally found in the dancing poses of the figures that are depicted in the early temples of Bhubaneshwar are a huge ring in one ear, the other being empty. At the neck there is a single beaded necklace. At the waist there is an Udara Bandha which has a rather ornamental look. The ankles of the dancers are generally free and unbedecked. Over the arms there are both armlets and wrist-lets. Both of them are rather broad for their kind.

Other important aspects which are found in the early temples of Odisha are a number of female figures in elaborate dancing attitudes. In fact, some of the dancing figures portray the basic stances of Odissi dance, the Chauka and the Tribhanga. It can be said that the early temples of Odisha are by far the most decorated monuments of the state.

Besides the innumerable cult images, depicting stories in stone was a special feature of the art of this period. Incidents from Shiva`s life, from the Ramayana and Mahabharata find elaborate representation in the base relief of the temples. Among other incidents, mention may be made of an elaborate procession of Shiva`s marriage, Parvati`s penance in water and Shiva`s receiving alms from Annapurna. All these scenes are found in the Parasurameswara Temple and the Bharateswara Temple. In the ruined temple of Swarnajaleshwara incidents depicted are the killing of a golden deer by Lord Rama, Bali-badha and the fight between Kirata and Arjuna.

Finally, it can be concluded saying that Shaivism one of the oldest religious form of Odisha had a strong influence on Odissi dance and the fact becomes clear from the various dancing poses that are found in the early temples of the state. The dancing poses of the temples have a close resemblance with the poses of Odissi dance.