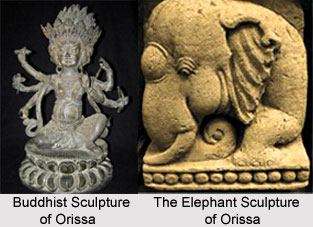

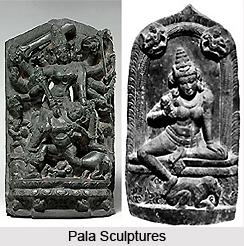

Several centres of sculptural art flourished simultaneously in different regions of the extensive empire of Bengal and Bihar between 8th and12th centuries AD. Several early sculptures discovered from Nalanda, Kurkihar, Bodh Gaya and Magadha exhibit characteristics of early Pala sculptures similar to the ones discovered in Bengal.

Several centres of sculptural art flourished simultaneously in different regions of the extensive empire of Bengal and Bihar between 8th and12th centuries AD. Several early sculptures discovered from Nalanda, Kurkihar, Bodh Gaya and Magadha exhibit characteristics of early Pala sculptures similar to the ones discovered in Bengal.

Origin of Pala sculpture can be attributed to the late Gupta style. However at a later stage the Pala style drifted away from its origin and developed its own style. The deviation was due to the fusion of classical mannerism with the indigenous style of Bengal. The mixed style continued through the 8th century and culminated in a specialized idiom of art in the early 9th century. The new style integrated a number of attributes that were common to the native Bengali sculpture and architecture. The sculptural images combined spiritual and mundane suggestions and were marked by sensuousness.

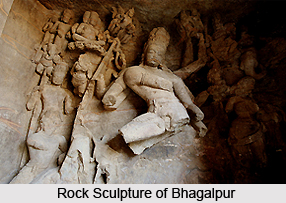

Most of the sculptures that have been discovered have been carved out of Rajmahal black basalt stone. Most of the sculptures are seen in Paharpur in Bangladesh. The main characteristic of majority of the sculptures is their flexibility. They are of the same size and executed in greyish or white spotted sandstone. They are similar to the huge number of terracotta plaques that decorate the facades of temple walls.

A few exceptionally well carved reliefs such as Krishna killing Kesin, Krishna uprooting the twin Arjuna trees are known for their expressiveness, lively action, and dynamic movement. Towards the end of the 10th century, the first renaissance of the Bengal School of Art took place when Mahipala I succeeded. The Bengal artists broke away from the shared traditions with Magadha. As there was a revival of political power it led to renewed artistic activities. Pala sculptures were created by the artists who belonged to north Bengal. The number of Brahmanical sculptures produced increased in the eleventh century. Some of the 11th century sculptures reveal a great advance in the elaboration of composition. Pure and minute carvings are features of several 11th century sculptures depicting Hindu gods and goddesses

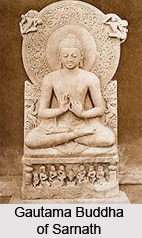

Well known 11th century sculptures most probably belong to the period of the second revival of the artistic activity under Ramapala who was the last powerful ruler of the Pala dynasty. Pala sculpture began as a genuine expression of religious experience. The early sculpture figures were heavy. In the tenth century there was an increase in the costumes, jewellery. The sculpture also became slightly elongated. In the eleventh century however more importance was given to vegetable decoration, ornamentation. Faces became more pointed. Excepting a few most of Pala sculptures of eleventh and twelfth century are stereotyped.

These sculptures were built in such a way so that they could stand the rough weather. The sculptures of the deities were carved out of fine grained black stones. Such sculptures have been discovered in all over Bengal. However towards the 10th century a local school of sculptural art developed. During this era the artists had to work within certain limitations and they followed the established canons. Yet these artists were successful in separating their art from the early Pala period. In fact it is recorded that during the reign of kings Devapala and Dharmapala an artist named Dhiman and his son Bitapala resided in Varendra. It is this father son duo who established the two schools of Pala art. The twelfth century sculptures have the soft, half-timid, sharp, amiable features that are prototypes of the Bengali style.