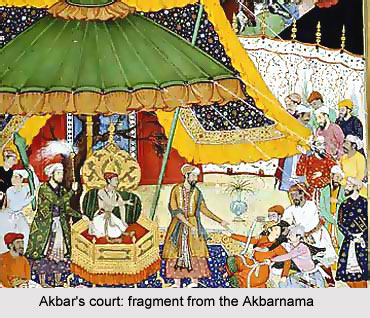

As per the historical record, it is said that the first painting of a portrait of Akbar was done by Abd al-Samad in 1551. In the Berlin album of Akbar, there is a painting of him with Hindal Mirza. A later period painting of Akbar`s court depicts Humayun in a tent.

As per the historical record, it is said that the first painting of a portrait of Akbar was done by Abd al-Samad in 1551. In the Berlin album of Akbar, there is a painting of him with Hindal Mirza. A later period painting of Akbar`s court depicts Humayun in a tent.

The painters recruited by Humayun had to change their individual style as per Akbar`s taste. During Akbar`s time, the Persian style of painting disappeared gradually. Akbar is regarded as the actual patron of Mughal painting even though he was reported to be illiterate and even dyslexic. The paintings of Akbar`s court included the album leaves and a bizarrely dressed, blue-eyed, wandering dervish somewhat figure. Akbar`s first and greatest project was said to be the copying and illustration of a romance already popular in India, the Hamza-name, the heroic developments of the Emir Hamza, a kinsman of the Prophet. This painting was done on cloth, with a stout paper backing, and its giant format is exceptional in Islamic painting.

It was not possible at the Akbar`s period to display the paintings for public exhibition even though Akbar had desired so. The small staff of Persian members recruited by Humayun could not do that. The creators of the beautiful paintings of Akbar`s court were not known exactly. But, it is assumed that the Muslim painters from Malwa and the Muslim courts of the Deccan (Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golconda), would have been done those paintings in markedly differing styles. They were also trained in wall painting (a probable source for many of the illustrations) but not in book illustration at all probably. Most of the paintings surviving today are not variable in quality and many must have been experiments without a practical sequel.

The great painters of Akbar`s time, Abd al-Samad and Mir Sayyid All were mainly responsible for executing the paintings. They used to work cut out in the administration of the studio, obtaining the paper and pigments, issuing them as necessary to the painters and accounting for them to the Treasury, and then seeing that the work was satisfactory and completed on time. The characteristic painting of Akbar was full with scenes flourished with adventure and drama, giants, monsters and demons, in a smoky palette of colours and this style continued till the end of his reign. The effect of these paintings was often brilliant, but bold rather than refined, combining Persian compositions and figures with the dark, jingly landscapes of the painting of pre-Islamic India. One of the finest paintings of Akbar`s court is the one, which depicts the 15 miraculous rescue of Hamza`s son, Nur al-Dahr, from drowning. In this particular painting, the work of at least four separate hands can be detected. It includes the water, painted in bravura linear style with white highlights, the figures, the forest landscape and some or all of the birds.

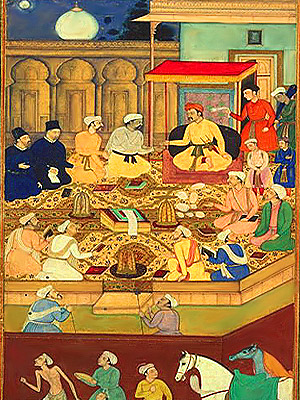

Some paintings of Akbar`s court have found place in the palace libraries, astronomical and astrological treatises, particularly star books and other works relevant to medicine, works of cosmography and geography. But now only few of these have survived. The earliest copy of the `Anvdri Suhayll` was made for him, which shows marked reminiscences of contemporary painting at Tabriz or Meshed. It contains twenty-seven full-page miniatures, but the margins of some of the other pages have pounced sketches in charcoal. During Akbar`s time, even the non-Muslim painters used to practice various works in his royal scriptorium. The painters were of Hindu, Jain, and even of Christian origin.

The painters of Akbar`s court like Manohar and Mansur illustrated double-page spreads and depicted the episodes from Babur`s campaigns, his visits to his relatives, his feasts and his hunts. Sometimes these paintings spread up to three or four pages, which depicted the gardens ordered by Babur, particularly near Kabul, the flora and fauna of India as the cameos. The subjects for illustration in most of the paintings also included Babur`s visit to the rock-carved idols below the fortress of Urwa, which showed his wide sympathies, which Akbar himself shared.

The painters of Akbar`s court like Manohar and Mansur illustrated double-page spreads and depicted the episodes from Babur`s campaigns, his visits to his relatives, his feasts and his hunts. Sometimes these paintings spread up to three or four pages, which depicted the gardens ordered by Babur, particularly near Kabul, the flora and fauna of India as the cameos. The subjects for illustration in most of the paintings also included Babur`s visit to the rock-carved idols below the fortress of Urwa, which showed his wide sympathies, which Akbar himself shared.

The Persian origins of the painters supervising the palace studio of Akbar and their ready access to Persian and Central Asian manuscripts figured largely in their paintings. In these paintings, primary colours were rare and there was a vast spectrum of smoky tones and figures were highly modeled. As most of these painters were trained in Europe, the European effect was very much evident in their paintings. These paintings had elegant gloss binding, margins illuminated in gold inks of contrasting tones with an almost infinite variety of detail, magnificently illuminated medallions and headpieces. Most of the painters of Akbar`s court used to treat standard subjects exceptionally. In one of such painting by Mukund, Bahram Gur is shown hunting gazelles with a background of a Flemish seascape with ships and mountains distantly sunlit.

The painting at Akbar`s court was so rich and diverse that it is difficult to single out one aspect but portraiture should be mentioned specially. These paintings also depict the historical narratives since the early fifteenth century under the successors of Tamerlane. But in spite of his heroic status in their eyes, there are no known portraits either of him, or of his son Shah Rukh or of his grandson Ulugh Beg. A concept of the dynastic portrait developed gradually during the Akbar`s time and it was at least done for the public audience halls of his palaces. Most of his portraits were in profile or half-profile style.

Akbar was very much attached to paintings and once in a private discussion of painting he remarked to Abu1 Fazl, "There are many that hate painting, but such men I dislike. It appears to me as if a painter had a quite peculiar means of recognising God; for a painter in sketching anything that has life, and in devising its limbs, one after the other, must come to feel that he cannot bestow individuality upon his work, and is thus forced to think of God, the giver of life, and will then be increased in knowledge."