The Muslim conquest of Deccan region by Ala ud-Din Khilji led to a gradual differentiation between north and south Indian music is noticed. Although orthodox Islam frowned upon music, the acceptance of the Sufi doctrines (in which music was often an integral part) by Islam made it possible for many Muslim rulers and noblemen to extend their patronage to this art.

The Muslim conquest of Deccan region by Ala ud-Din Khilji led to a gradual differentiation between north and south Indian music is noticed. Although orthodox Islam frowned upon music, the acceptance of the Sufi doctrines (in which music was often an integral part) by Islam made it possible for many Muslim rulers and noblemen to extend their patronage to this art.

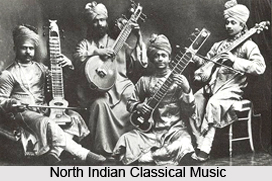

History evidences that musicians from Iran, Afghanistan, and Kashmir were at the courts of the Mughal Emperors Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is quite evident that it was Indian music which captured the imagination of the Muslim rulers. Famous Indian musicians such as Svami Haridas, Tansen, and Baiju Bavra have left their impress on the history of north Indian music as per¬formers and innovators. Muslim musicians took to the performance of Indian music and added to the repertoire by inventing new ragas, taals, and musical forms, as well as musical instruments. This Muslim influence was largely effective in the north of India and undoubtedly helped to further the differen¬tiation between north and south Indian music, the two classical systems which are now generally referred to as Hindustani and Karnatak (Carnatic) music, respectively.

The Muslim patronage of music has had two main effects on the music of north India. The first was to de-emphasize the importance of the words of classical songs, which were originally composed in Sanskrit. Sanskrit songs were gradually replaced by compositions in various dialects such as Bhojpuri and Dakhani. There were also compositions in Urdu and Persian, some of which can still be heard. The textual themes of the songs were often based on Hindu mythology and yet Muslim musicians sang these songs and the songs were well accepted by the listeners and singers as well. On the reverse side of it, the Hindu musicians sometimes sang songs dedicated to Muslim saints. The best example of this attitude is to be seen in the poetry of the Muslim ruler Ibrahim Adil Shah II of the Deccan, who, in his Kitah-i-Nauras, composed at the beginning of the seventeenth century, wrote poems in praise of both Hindu deities and Muslim saints. These poems were sung in specified ragas by both Hindu and Muslim musicians.

The second effect of court patronage on Indian music was to produce an atmosphere of competition between musicians, which placed no little em¬phasis on display of virtuosity and technique. A great deal of importance was also placed on the creative imagination of the performing musician and gradually the emphasis shifted from what he was performing to how he was performing it. Traditional themes remain the basis of Indian music, but, in north India particularly, it is the performer"s interpretation, imagination, and skill in rendering these that provide the main substance of modern Indian music.

Beginning about the sixteenth century, a direct connection between the textual literature and modern performance practice was seen. An im¬portant feature of most of these texts is that a new system of classifying ragas in terms of scales was introduced. These scales are called mela in south India and that in north India. The north Indian music was evolving through its contact with the Muslims and the north Indian musicians were little influenced by the musical literature written in Sanskrit because many of them were Muslim and had no back¬ground in the language. In addition, most Hindu musicians were unable to understand Sanskrit, which had become a scholarly language in north India. South India had, however, become the centre of Hindu learning, and Sanskrit literature continued to play an important part in the development of its music. Thus north Indian music seems to have developed, for the most part, quite intuitionally during this period, and it is only in this century that musical theory has once again begun to come to grips with performance practice and to influence its development.

There are about ten more scales used in north Indian music. In north Indian music, the beginnings of a different method of raga classification are observed. There a number of ragas are given generic names, such as Kalyan, Malhar, and Kanhara, with specific names used to distinguish the various ragas within the same genus.