Neo-Classical architecture in India was initiated by the European colonists who brought with them the vast concept of their `world view` and a baggage full of the history of European architecture including Romanesque, Neo-Classical, Gothic and Renaissance. At Chennai (Madras) large number of security asked for wider growth outside the confines of the fort walls. This resulted in the spread of Madras `flat-tops`, garden houses set in large, landscaped compounds. These houses, with deep verandahs to offer shade, were adapted from Palladian prototypes. Pedimented centerpieces and curved bays to the garden frontage were common themes, imparting a sense of grandeur and presence as well as providing a welcome respite from the severe rays of sun. Some of the notable survivals include the Adyar Club, the old Madras Club, Brodie Castle and Government House, Guindy.

Neo-Classical architecture in India was initiated by the European colonists who brought with them the vast concept of their `world view` and a baggage full of the history of European architecture including Romanesque, Neo-Classical, Gothic and Renaissance. At Chennai (Madras) large number of security asked for wider growth outside the confines of the fort walls. This resulted in the spread of Madras `flat-tops`, garden houses set in large, landscaped compounds. These houses, with deep verandahs to offer shade, were adapted from Palladian prototypes. Pedimented centerpieces and curved bays to the garden frontage were common themes, imparting a sense of grandeur and presence as well as providing a welcome respite from the severe rays of sun. Some of the notable survivals include the Adyar Club, the old Madras Club, Brodie Castle and Government House, Guindy.

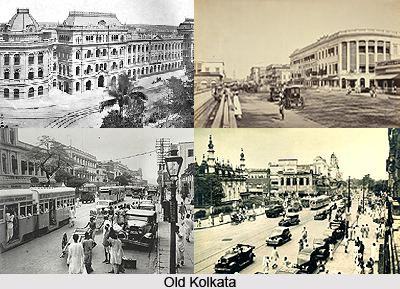

With the resumption of the control of Kolkata by the British under the command of Lord Clive in the year 1757, after the defeat of Siraj-Ud-Daulah in the Battle of Plassey and the notorious incident of the Black Hole Tragedy, a major was visible in the form and pattern of European settlement. A massive new fort was constructed, based on the seventeenth century concepts of fortification of Vauban. The new Fort William was the most important symbol of British military power in Asia which took thirteen years to be completed and it cost over two million pounds at that time.

Unlike the Fort St George, where all the principal public buildings were contained within the fort, at Kolkata the new public buildings were placed outside the ramparts. This was a significant change. The static form of development established on defensive strongholds paved the way for a much more dynamic form of dispersed settlement, one more conducive to expansion and unrestricted growth. This was a reflection of growing power and security and increased wealth.

The new fort changed the entire layout of the city of Kolkata, for in order to command an unrestricted field of fire, a huge open space, the Maidan, was cleared. This not only made the fort unassailable but formed a huge setting around which an elegant collection of public and private buildings arose. The formation of the Maidan in the year 1780 provided scope for the European merchants to express their newly found wealth in a more visible form. The primitive thatched bungalows were swept away, to be replaced by some of the grand classical houses which reflected the aspirations and status of their European owners.

The architectural designs of these fine Indian mansions were in an accomplished classical style, which marks the first stage in the adaptation of European forms of architecture to an Indian context. Large numbers of the structures were similar to the garden houses at Chennai; a well-proportioned cube of two or three storeys set in a garden compound with the inner rooms screened by a colonnaded verandah or portico. The setting of the houses in separate garden areas was prompted as much by good planning and it encouraged a cool flow of air and reduced the risk of disease, as by a desire for exaggerated individual impact. Thus, settlement was widely dispersed, with considerable distances between the houses. Transport was either by carriage or palanquin. Entrance porches became portes-cochcres, often of enormous proportions, to accommodate the elephants of visiting grandees arriving by howdah. The materials used for the construction were always the same, which include a rough brick core covered with Madras chunam, a form of lime stucco made from burnt seashells and polished to a high sheen, although in the harsh climate of Bengal this deteriorated to reveal the sham beneath the facade.

With the development of the city of Kolkata gathering momentum, the more central districts like the Chowringhee and the Esplanade, acquired a continuous street frontage of boundary walls, screens and gates, which complemented the fine classical architecture of the houses. The serial construction of these houses over many decades was a process of continuous refinement and adjustment to local conditions. Intercolumniation was exaggerated to provide greater shade; proportions were bastardized to suit the context and louvered screens of wooden ribs of moist plaited grass were hung between the columns of the verandas to provide a cool flow of air. Over saving hoods and fretwork valances were added to the window openings to provide additional relief from the climate. In time, these became ornamental art forms in their own right, a recurrent theme in Anglo-Indian architecture.

Even if most of these delicately constructed houses have been demolished or submerged in the encroaching bazaars, a number of well-preserved examples can still be seen in Chowringhee, Alipore and Garden Reach. Warren Hastings`s house at Alipore, described as a `perfect bijou` when constructed in the year 1777, and reputedly haunted by his ghost, is a notable example, together with nearby Belvedere, now the National Library. Various other survivals include the Tollygunge Club or the Royal Calcutta Turf Club and Loretto Convent in Chowringhee; offer a rewarding insight into the `city of palaces`.

With the dominance of European architecture in the city of Kolkata, native merchants adopted European styles for their own houses and mansions in a curious process of hybridization. It is not uncommon to find European houses enriched with Hindu-style capitals or a compendium of strange motifs highlighted in gaudy colours. This cross-fertilization of architectural styles even affected the mosques. The mosque of Tipu Sultan, for instance, is a fascinating example of European forms and details being applied to a functional Islamic building.

Kolkata became the effective capital of British India, and the East India Company thus kept on erecting public buildings which echoed this newly found self-confidence. The transformation of Kolkata and Chennai (Madras) from commercial trading enclaves into elegant neo-classical cities coincided with changing perceptions of British activity in India. Trade remained important, but the conscious reflection of the values of Greece and Rome in the monumental civic architecture of the period reflected a growing awareness of a wider political and imperial role. This was expressed in a number of buildings throughout India. In Chennai (Madras), the ambitious remodeling of Government House by the second Lord Clive and the construction of a huge monumental basilica as a Banqueting Hall proclaimed this change in British perceptions. The grand pedimented ends of the Hall were enriched with arms celebrating British triumphs at Plassey and Seringapatam.

In Kolkata the arrival of Lord Wellesley, elder brother of the future Duke of Wellington, as Governor-General marked a profound change in British self-awareness. He, more than any other individual, stamped an Imperial dimension on the British East India Company rule.

In Kolkata the arrival of Lord Wellesley, elder brother of the future Duke of Wellington, as Governor-General marked a profound change in British self-awareness. He, more than any other individual, stamped an Imperial dimension on the British East India Company rule.

The most striking manifestation of this change was the construction of the Government House, in the year 1803 to the designs of Captain Charles Wyatt. Modelled on Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, the house was set in its own large compound at the northern end of the Maidan. The main approaches were adorned with monumental entrance screens crowned with lions and sphinxes, recalling screen at Syon House by Robert Adam.

With the growth and development of Kolkata, it blossomed into a city of palaces, a magnificent expression of the rising British power. A whole series of classical perspectives was formed, with vistas terminated by prominent public buildings and monuments, such as the Town Hall, the Mint, Metcalfe Hall and the La Martiniere schools. European ideas of townscape, planning and layout were imposed on an Asian city on a scale which had never been witnessed before.

The same process can be recognized elsewhere in the British ruled India. In Mumbai a spectacular New Greek town hall was commenced in the year 1820, the finest neo-classical building in India. At Murshidabad, a fine new palace was designed by General Duncan Macleod for the Nawab, founded on Government House, Kolkata, while at Chennai the shoreline boasted a list of classical buildings which provoked comparison with the Mediterranean in the age of Alexander.

The model for many British churches in India is St Martin-in-the-Fields, London. In several early colonial churches the influence of great architects like Wren and, in particular, James Gibbs was visible, and this was not just limited to India. St Martin`s offered an appropriate model for use throughout the British Empire. Its plan, elevations and distinctive tiered spire recur again and again from Australia to North America and from South Africa to India. It continued to be used long after the Baroque style had been superseded by neo-classicism and the Gothic Revival.

The influence of St John`s, Kolkata, and Gibbs`s London prototype was so persuasive that it is a surprise to find out the occasional aberration, such as St James`s Church, Delhi, designed by Colonel Robert Smith and constructed between 1828 and 1835 in memory of the famous Colonel James Skinner in fulfillment of a vow he made when wounded on the battlefield. This was designed on a Greek cross plan and crowned by a Baroque dome, with each arm terminated by a Doric portico, but such exercises remained the exception rather than the rule.

Most of these churches possess splendid examples of funerary sculpture by leading sculptors of the day, like John Bacon and John Flaxman. These were commissioned from India and sent out from London as ballast in the ships. Elegant marble monuments in crisply executed neo-classical designs expressed deep sincerity of feeling. Common repetitive themes were used in India and in England; the pedimented stele with draped figures in low relief mourning beside a pedestal or urn representing `Resignation`, or draped female figures contemplating the Bible or the heavens. Some are spectacular compositions in high relief. St Thomas` Cathedral, Mumbai, St Mary`s, and St George`s, Chennai and St John`s, Kolkata, have outstanding collections of mural monuments which should not be missed.

After the traumatic events of the Sepoy Mutiny, the balance of British commercial interests changed. Kolkata remained pre-eminent, but Chennai became less important. The centre of activity shifted to the west coast and to the emerging city of Mumbai in the state of Maharashtra, which in less than three decades exploded from a forgotten backwater to a great Imperial city.

The rapidity of its growth was phenomenal. In the year 1864, there were thirty-one banks, sixteen financial associations and sixty-two joint stock companies. This sudden economic boom owed much to the slump in supplies of American cotton to the Lancashire textile mills on the outbreak of the American Civil War. Overnight Mumbai became `Cottonopolis`, a vast clearing-house for Indian produce. Prices climbed to staggering levels. The values of land increased. Speculation in land became frenetic. This inflow of unprecedented wealth overlapped with the arrival of a new Governor, Sir Bartle Frere. Under his enlightened and energetic direction the city was transformed into the Gateway to India. The old town walls were swept away. A new city began to take shape in the latest fashionable Gothic style. Frere was determined to give the city a series of public buildings worthy of its power, wealth and potential. He stipulated that the designs should be of the highest architectural caliber, with conscious thought given to aesthetic impact.

The great neo-classical town hall, constructed by Colonel Thomas Cowper between 1820 and 1835, was, of course, already there, together with the venerable St Thomas`s Cathedral. Frere nurtured this image of Imperial power. As a result Britain`s finest heritage of High Victorian Gothic buildings now lies in Mumbai.