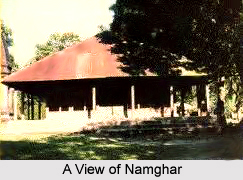

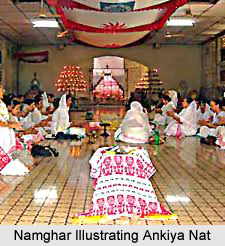

Namghar is the common property of the villagers, where they meet each evening to listen to the recitations of the sacred scriptures by the Pathaka, and to join the evening prayer. The Ankiya Nats were written more with a -religious motive than for secular enjoyment. Hence they were staged in the village Namghar (the prayer-hall), on occasions like Janmashtami, Dol Yatra and Rasa-Purnima. Later on, they came to be staged on festive occasions, for example, on full-moon nights, during seed-time and harvest, and whenever the villagers were free from agricultural work. Sometimes special houses and temporary sheds or rabhas are constructed for such dramatic performances. Madhavadeva is said to have set up at Barpeta a big hall called barghara or rangiyal-ghara to stage his plays Bhojana Vihara and Dadhi Mathana.

Namghar is the common property of the villagers, where they meet each evening to listen to the recitations of the sacred scriptures by the Pathaka, and to join the evening prayer. The Ankiya Nats were written more with a -religious motive than for secular enjoyment. Hence they were staged in the village Namghar (the prayer-hall), on occasions like Janmashtami, Dol Yatra and Rasa-Purnima. Later on, they came to be staged on festive occasions, for example, on full-moon nights, during seed-time and harvest, and whenever the villagers were free from agricultural work. Sometimes special houses and temporary sheds or rabhas are constructed for such dramatic performances. Madhavadeva is said to have set up at Barpeta a big hall called barghara or rangiyal-ghara to stage his plays Bhojana Vihara and Dadhi Mathana.

During the day, the Namghar becomes a seat of justice where major village disputes are settled and topics of local interest are discussed by the leading villagers. On festive occasions, it converts itself into a public theatre. So the Namghar plays a significant part in the social and religious life of the Assamese people. It has not only preserved the cultural traditions of Assam but immeasurably helped the growth and development of Assamese music, dance and drama. The Namghar is a two-roofed thatched structure generally measuring more than fifty feet in length, and is rectangular in shape (like the vikrista type of play-house mentioned in the Natya-sastra).

Close to it, at one end, is built a small house called the Manikut (garbhagrha of a Hindu temple), where an image or a copy of a religious scripture is placed on a simhasana, a wooden throne. Except the initiated few, others are not allowed inside the Manikut. The Namghar consists of two wings. The one near the Manikut is reserved for the Adhikar, the pontiff, who usually presides over the performance, and for the Brahmanas; and the other for the actors. The side close to the entrance forms the general auditorium (ranga- mandapa) where the audience sit on mats or on the bare ground. There are two rows of pillars in the middle of the hall, and seats near some are reserved for distinguished visitors. About two-thirds of the space between the rows of pillars makes the stage or ranga-bhumi, which has no raised platform.

Close to it, at one end, is built a small house called the Manikut (garbhagrha of a Hindu temple), where an image or a copy of a religious scripture is placed on a simhasana, a wooden throne. Except the initiated few, others are not allowed inside the Manikut. The Namghar consists of two wings. The one near the Manikut is reserved for the Adhikar, the pontiff, who usually presides over the performance, and for the Brahmanas; and the other for the actors. The side close to the entrance forms the general auditorium (ranga- mandapa) where the audience sit on mats or on the bare ground. There are two rows of pillars in the middle of the hall, and seats near some are reserved for distinguished visitors. About two-thirds of the space between the rows of pillars makes the stage or ranga-bhumi, which has no raised platform.

The orchestra and the actors sit surrounding the space meant for the stage. There is no other special arrangement for the stage than an arkapor (pati or apati of a Sanskrit play), a white curtain which is used when the principal actors come out from the cho-ghar (Skt. chadma-grha), and the green room, situated near the Namghar. All the actors do not appear on the stage at the same time; they wait in the cho-ghar till their presence on the stage is announced by the Sutradhara. Sometimes, after playing their parts in a particular scene, they do not leave the stage but sit with the orchestra awaiting their next appearance. The general term for actors in Assamese is Bhavariya (from Skt. bhavata), i.e., one who produces bhava or emotion in the mind of the audience. Those who play the dance-roles are called nartaka, natuva or nata (as they represent the actions of others). Those who supply the orchestra are called gayan, the singer, and bayan, the instrumental musician.

Then, as now, there were no professional actors; they were recruited from the villagers. Assamese acting is thus the work of amateurs. The roles of the principal characters of Krishna and Rama and their consorts are played by handsome young men especially of the higher castes, as they in their dramatic roles have to receive the obeisance of the other actors and of the audience. These actors are supposed to observe a fast before the Bhavana is presented. Female roles are performed generally by teen-agers having a feminine appearance. Unlike, however, as with the earlier Sanskrit theatre, the reputation of actors of an Assamese Bhavana was never low or dishonourable. Even men of erudition, great artistic attainments and high social, religious, and political status played roles in an Assamese Bhavna without loss of prestige and honour. The Adhikar, when present at a performance, becomes preksapati, the guest of honour or sabhapati. He receives obeisance from the actors as well from the audience. The audience is addressed as sabhasad or samajik. The actors have special sets of dresses. These are preserved in the house of the khanikar, a painter and maker of wooden and earthen images by profession. His services are indispensable to the actors.

He makes the image of God for worship, prepares the effigies (cho) and masks (mukha), makes arrangements for necessary costumes required in different performances, constructs the weapons of battle, such as sword, shield, bow and arrow, discus, club, etc., helps in the general make-up of the actors in the green-room, and has to provide ariya and mata, that is, the torches, when the performance takes place at night. The khanikar or the maker of the masks is a man of many attainments, and his services are used mainly for the prerequisites outside the stage. He derives his inspiration and his skill in the arts from an accumulated fund of hereditary knowledge. He has not only imagination and ability required to make grotesque and fantastic life-size masks, but has also, to execute them properly, an accurate knowledge of human physiognomy and of the nature of the animal world, and, above all, a full acquaintance with the dramatic requirements.

Besides masks, the dress and appearance of the characters are very carefully made up as regards both design and colour. The Sutradhara wears a ghuri or crinoline with broad lace buttons and flowing to the ankle; a phatau or a vest with or without sleeves, and a colourful karadhani or waist-band. He ties a particular type of turban (pag) to his head. The gayan-bayan troupes wear a costume like that of the Sutradhara but of simpler designs and homelier materials. The other male characters put on dhuti coming down to the knee and a waist-coat. These may be colourful and embroidered according to the rank of the character who wears them. The costumes for female roles are carefully chosen, their main dress consisting of mekhela (flowing skirt), riha (breast-cloth) and chadar (shawl). They wear ornaments in profusion, of course, of tinsel.

The actors use paints for their make-up, befitting their roles. The conspicuous paints are generally prepared by mixing hengul (cinnabar) and haital (yellow-orpiment). The different colours, whether used singly or in combination, have traditional significance; for example, Krsna, with his long head-dress, called kiriti, is painted in syama i.e., blue black, a Brahman or mendicant in white, a violent and brutal man in red, the devils in black. Effigies and masks were probably in use in Assam, especially in popular dancing, prior to the introduction of the drama by Sankaradeva. Chihnayatra, produced by Sankaradeva and his companions shows the use of mask which was worn by Garuda, the vehicle of Lord Vishnu. The variety of masks that are used in Assamese Bhavana may be classified into three types: (i) those representing grotesque forms or hideous persons, such as Ravana, the king of the Raksasas; Kumbhakarna, his brother; Lord Yama, the god of death; Lord Hanuman, the lord of monkeys, etc.; (ii) those for different animal-actors such as Garuda, Kaliya-serpent, boar, monkeys, Jatayu-bird, etc.; (iii) the comic masks of the buffoons and the jesters.

Masks that cover the head and the face are generally in use. But in many performances elaborate life-size effigies are indispensable, particularly in Ravana-badh, Kaliya-daman, and Syamanta-haran. In Ravana-badh Bhavana, a life-size mask with ten heads and as many as hundred hands is worn by Ravana; Kumbhakarna and Hanuman have also respective life-size masks. In Kaliya-daman and in Syamantaharan life-size masks are worn by Kaliya serpent and by Jambuvanta, the bear-king with whom Krishna fought to rescue the gem syamanta.

To make them light in weight and make movements easy with them on, large-size masks are made of bamboo splinter bars and cloth. The buffoons wear small masks prepared from clay, cloth, rough paper and tree-bark; the bark of the plantain tree is also used to serve temporary purposes. Head-dresses and upper masks, i.e., masks for head and face, are carved out of wood and hard bark-sheet. Thus this new genre of literature, combining different forms of art and giving them a composite expression of its own, happens to be the most remarkable phenomenon in the history of Assamese literature. Although an ethicoreligious mood is the dominant note of the Ankiya nats, they have admirably dovetailed the dance-tradition of the soil into the classical tradition of drama and music along with occasional gleanings of art-fragments from different parts of India.

The Namghars, which were set up as central religio-political institutions of the villages, played a great part in their intellectual and cultural activities. Here not only Sastras and literary masterpieces were recited, but great problems of life, philosophy and religion were discussed and` debated; and the village people learnt here what they did not know before and received new ideas and experiences. The Namghars served, and are serving still now, as a panchayat-hall, where the villagers gather not only for religious purposes but also to discuss many current problems of the village and community life and political as well as economic and social subjects. This institution helps to impart unity to Assamese village life.

Furthermore, both the satras and the Namghars led to the creation and development of drama, music and the stage. These three are most powerful instruments for popularising culture as they appeal to nearly every one. The Ankiya Nats, which are full of music and dance, are acted even today in the Namghars, and the entire village assemble to see on the stage stories from the great works, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Bhagavata Purana, dealing with deepest problems of human life and religion. The Vaisnavas introduced many new festivals and saints` days in their calendar, and these doubtless widened the scope for dramatic performances and recreations for the mind and spirit of the worry-ridden common man. The researchers have already referred to the great revival of the study of Sanskrit language during the Vaisnavite period that brought about a renaissance in the intellectual life of the country not seen in the earlier ages.

This Sanskrit or classical influence proved a great benefit to the cultural life of the people in all respects: it gave the Assamese language a rare distinction, and created in it a literature which is expected to stay for all times; it also tempered, refined and polished the manners and character of the Assamese society, built of diverse elements.