Nambudiri Brahmins of Kerala claim in the legend of Parasurama to have arrived first in the state, which is not even worth examining; they are physically a different type from other Malayalis, fairer-skinned, taller, narrower of head, and it is obvious that they entered Kerala on the wave of Aryanization that swept South India some centuries after the coming of the Dravidians. Even at the time of their ascendancy as the elite of Kerala, they were never more then a thin, insecure top crust on society and it is doubtful if proportionately linear numbers then were any higher than today, when the Brahmins of Kerala number in all about 300,000, or less than two percent of the total population. The castes below them, Kshatriyas, Ambalavasis and Samantans, almost certainly did not arrive in Kerala as separate groups.

Nambudiri Brahmins of Kerala claim in the legend of Parasurama to have arrived first in the state, which is not even worth examining; they are physically a different type from other Malayalis, fairer-skinned, taller, narrower of head, and it is obvious that they entered Kerala on the wave of Aryanization that swept South India some centuries after the coming of the Dravidians. Even at the time of their ascendancy as the elite of Kerala, they were never more then a thin, insecure top crust on society and it is doubtful if proportionately linear numbers then were any higher than today, when the Brahmins of Kerala number in all about 300,000, or less than two percent of the total population. The castes below them, Kshatriyas, Ambalavasis and Samantans, almost certainly did not arrive in Kerala as separate groups.

The Nayars are lighter in colouring than the Tamils and often they seem more skin in facial structure to North Indians; this may be due to their steady inter-breeding with the Nambudiri Brahmins through the custom of sambandham, a form of morganatic marriage peculiar to Kerala by which the younger sons of Brahmin families could form relationships with Nair women, the children remaining Nayars and thus introducing a new element into the race.

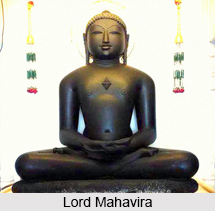

Though the claim of the Nambudiri Brahmins to be descended from the sixty-four families of original inhabitants, who came to Kerala when the land was still steaming after being called from the sea by Parasurama, cannot be accepted, there is no historical record of their arrival, and all we can assume is that it was one of the incidents which took place during the gradual Aryanization of South India. That process involved first an introduction of Hindu religious concepts and deities and later the adoption of the Hindu social system; local Dravidian and even pre-Dravidian cults were not eliminated, but were merely integrated with the new religion, and their deities were regarded as manifestations of the great Hindu gods, particularly of Lord Shiva, Lord Vishnu and Parvati in her various beneficent and maleficent forms. Shilappadikaram makes it clear that the process of religious integration had reached an advanced stage by the end of the second century A.D., yet there is no suggestion of a temporal or even an exclusively spiritual domination by the Brahmins. The temples of local deities - even if they had been recognized as manifestations of Brahminical gods - appear to have been served by their own non-Brahminical priests, while, side by side with the Brahmins, Jain and Buddhist teachers had established themselves; even Prince Ilango Adigal, author of Shilappadikaram, became a Jain monk

With the dominance of Buddhism in the north, the Nambudiri Brahmins started abandoning their homes in northern India and moved with their joint families to Kerala, where the tolerant Chera chieftains (whose descendants were to give such warm welcomes to Christian and Jewish emigrants) offered them land and helped them to set up temples. At this time, when a prince of the reigning dynasty chose to become a Jain monk, it is obvious that the Nambudiri Brahmins had no opportunity to assert their supremacy in any but a sacerdotal context. Indeed, Keralan historians are agreed that it was only between the eighth and the ninth centuries that the Nambudiri Brahmins sought and gained the extraordinary social ascendancy which they enjoyed throughout Kerala during the middle ages and retained in some areas of the state up to the end of the nineteenth century.