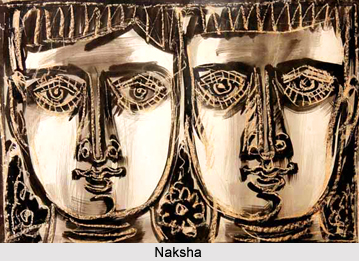

Naksha is a literary genre in Bengali literature. It comes from the Persian word `Naqshah` meaning map, drawing, sketch or model. In literature, it is usually rendered as a satirical sketch. However, it must be remembered that though Nakshas are often satirical and comical, it is not necessarily so. Often, the Naksha is held to be an empirical category of Bengali prose with a tradition complementary to that of the novel. The Naksha was first used in this meaning in 1862 in Kaliprasanna Sinha`s Hutom Pyachar Naksha, Naksha of the Owl.

Naksha is a literary genre in Bengali literature. It comes from the Persian word `Naqshah` meaning map, drawing, sketch or model. In literature, it is usually rendered as a satirical sketch. However, it must be remembered that though Nakshas are often satirical and comical, it is not necessarily so. Often, the Naksha is held to be an empirical category of Bengali prose with a tradition complementary to that of the novel. The Naksha was first used in this meaning in 1862 in Kaliprasanna Sinha`s Hutom Pyachar Naksha, Naksha of the Owl.

Some writers are of the view that there are certain features of Naksha which are briefly as follows. Nakshas give a general description of social circumstances and do not focus on specific events; scenic descriptions are dominant; a general perspective on social issues is developed; and characters/protagonists merely help to bring out the above-mentioned features; they function as symbols of their class, not as singular personalities. However, though these features are more or less applicable to Nakshas, merely viewing the Nakshas as possessing these features would delimit the genre to quite an extent. Some of the earliest Nakshas, like Bhabanicharan Bandyopadhyay`s Nabababubilas, The Merriment of the New Babu, and Nababibibilas, The Merriment of the New Bibi, are not pure specimens of the genre since they show aspects of Kahini, narration, as well. Also, fictionality is an important aspect of the Naksha, which has not been covered by the above mentioned features. A better understanding of Naksha comes from the content of those pieces. They consist of a limited range of topics from mostly urban social life, and its `mirroring`, corrective function within society. Here again, not all texts on Naksha fall under this category. The Nakshas were written in a period without stable norms for prose writing.

What primarily sets the Nakshas apart from earlier literary production of Bengal is the way they address the social context. These new narrations mark a drastic change in the communicative directives of Bengali literature. Their subject matter is derived directly from a new sort of awareness of contemporary society, and they communicate the perceptions of that society back onto it. The cultural identity of educated Bengalis was from the start one of the chief issues under discussion. For the first time, literate Bengali Bhadralok or gentle society can be seen speaking about itself. There was no `speaking about oneself in pre-modern Bengali literature. The standard protagonist of Nakshas in nineteenth-century Bengal is the Babu, (together with the Bibi, his female counterpart) and his appearance, lifestyle, activities, social circumstances etc. And the standard residence of Babus, Bibis and everything new, noteworthy and strange is the growing metropolis of Kolkata.