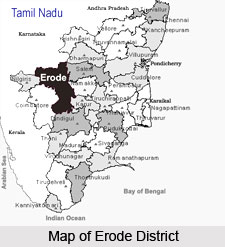

Muslim society in Tamil Nadu contains three major groups. They are the Tamil Muslims, Dakhni Urdu Muslims and Tamil Dakhnis. The elites of each of these groups attempted to push the identities of their respective groups in different directions. In the year 1931, Muslims numbered a million and formed, on an average, about five percent of the total population of the state of Tamil Nadu. The largest concentrations were in the districts of Thanjavur, north Arcot, Tirunelveli, and Ramanthapuram, in that order. Various social groups and classes played a very significant role in the formation of political identities among the Muslims living in Tamil Nadu state. Vital landmarks in their history spanning more than twelve centuries also have a bearing on their political responses and actions in modern India.

The followers of Islam or Muslims living in the state of Tamil Nadu in India were divided among the lines of religious doctrine, class and language. A large number of them spoke the Tamil language. However, in the northern parts of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, mainly in the city of Chennai, Chengelpet, south Arcot, north Arcot, Salem, and Tiruchirapalli district, a small but substantial section of them spoke the Urdu language. The three prominent social groups among the Muslims living in Tamil Nadu are Tamil speakers (hence known as Tamil Muslims), Urdu speakers (hence known as Dakhni Urdu Muslims), and a third and new sociological category of the Tamil Dakhnis, who share the history of both earlier groups.

The myths about the origin of Tamil Muslims refer to Arab traders having brought Islam to the state of Tamil Nadu in the seventh century AD. Based in the coastal towns of Tamil Nadu, these Arab traders married local Tamil women whose offspring, a mixed Arab-Tamil race, came to be the first Tamil Muslims. Based on the myths of origin and the areas where they had originally settled, Tamil Muslims were further subdivided into Marakkayars and Rowthers. While the Marakkayar and the Rowther were tow clearly identifiable subdivisions among Tamil Muslims in their origin myths and social organization, another term used for Tamil Muslims was Labbai; its meaning is unclear.

The prominent feature of Tamil Muslim society was their dispersal through migration. Over the centuries, they had spread in the whole of South-East Asia - Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, Hong Kong, and Indo-China-as petty traders, merchants and labourers. The Tamil Muslim migrants played a significant part in the development of Muslim literature and the press in the Tamil language. Tamil Muslim migration to South-East Asia was part of the larger Tamil diaspora, which gave Muslims another opportunity to define themselves as Tamil away from mainland China.

The most significant thing is that the Muslim politics subsumed the categories of Marakkayar, Rowther, and Labbi under the group of Tamil Muslims. Even if the origin myths and businesses determined social relations among Tamil Muslims, what must be noted is that these categories carried little relevance in the larger political processes in the region. The Tamil language and Islam were the main parameters of definition of these groups. Hence, they are defined as Tamil Muslims. Any account of Tamil Muslims shows that they had a long tradition of being Tamil while being Muslim.

The Dakhni Urdu elites were among the earliest to organize as a community under colonial dispensation. They constituted associations and looked for representation within the bureaucratic structure of colonial rule. They associated themselves with Muslim politics in northern India, and in the process presented a pan-Indian Islamic identity. They were later on joined in this process by Tamil Dakhnis. Among Tamil Muslims, there were groups and elites that asserted both a regional Dravidian/Tamil identity and a pan-Indian Muslim identity. It is significant that the assertion of a Tamil identity by Tamil Muslims was closely connected with the decline of the dominance of Dakhni Urdu Muslims, who had the earliest access to the seat of governance in Fort St. George.

Dakhni Muslims are also referred as Dakhnis. The Dakhni Urdu-speaking Muslims are more in common with their co-religionists in other parts of south India, like the Urdu-speaking Muslims of Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Maharashtra, and, in lesser ways, with the Urdu-speaking Muslims of north India. Dakhni Muslims were further subdivided into the Shia sect and Sunni sect. `Dakhni Muslim` itself is an umbrella category, which blankets intra-cultural divisions established on the origin myths of the various groups like the Navayats, Syeds, Sheikhs, and Pathans.

Among all the divisions inside the Dakhnis, the ones that are vital politically are the differences between the Shiahs and the Sunnis, who had separate mosques, theologies, seminaries, government kazis and community organizations. The arrival of the Dakhnis, dated to the time of the invasion of the Bahmani Sultans in the sixteenth century, was significant in two ways. The northern parts of the Tamil Nadu state where they settled recorded a solid increase in the population of the Muslims and the Tamil Muslim population at this place was very small. The Dakhnis introduced to Tamil Nadu the Islamic religious and linguistic traditions powerfully influenced by the customs of the Muslims living in the northern parts of India. The cultural differences that separated them from their Tamil-speaking co-religionists have been perceived as causing political divisions among the Muslims of the region.

The Dakhni and Tamil Muslim groups did not encourage inter-marriage, and differed in their kinship patterns and their own social structures. However, both shared common ritual spaces and a Sufi tradition. If kinship, marriage and social structure, apart from language, were the prominent sources of difference between them, then ritual space and the Sufi tradition were the sources of commonality or unity between the two groups.

The Dakhni elite, like the Tamil Brahmins, were among the first to join the bar, bureaucracy and the teaching profession. These professions restored to those who succeeded in joining them their sense of social position and power. From their ranks were drawn the proponents of pan-Indian Islam in the region. By contrast, Tamil Muslims, who as seafarers and merchants had relied less on the state power and gained more from the maritime trade that accompanied the European expansion, were slower to feel dispossesses. It was only in the early twentieth century that some Tamil Muslims joined the Dakhni elite on the political bandwagon of pan-Indian Islam.

Tamil Dakhnis are a new subdivision that emerged in the early twentieth century in south India. Their emergence was the result in the late nineteenth century of the migration of Muslims from Thanjavur to Vaniyambadi and elsewhere in the district of north Arcot. This migration was partly because of the famine and inter-caste conflict, but it was also promoted by the expansion of the leather trade in the Arcot region, blessed with an abundance of the bark which is necessary for the tanning process. Even to this day, many Muslim families here are said to be known by their places of origin in Thanjavur. While the Tamil Dakhni elite were sought after for their patronage and philanthropy, their social position within the larger Muslim society was unenviable. Dakhni Urdu Muslims never accepted them as `pure Muslims` or `pure Urdu speakers`. Indeed, they were often referred to mockingly by the Dakhnis as `Urdu Labbais` to indicate a lower rank that the `pure` and endogamous Urdu Muslims.

However, whatever the amusement that the Tamil Dakhnis may have provided, the profits of the leather trade gave them considerable political influence in the Tamil Nadu state. They invested heavily in Muslim education. In this effort, they drew in different groups of Muslims in south India, including those from Malabar and south Kanara. The Tamil Dakhnis transformed the mercantile capital of the Arcot region into cultural capital and contributed to the formation of Muslim identities in modern Tamil Nadu.

The economic condition of most of the Muslims in Tamil Nadu was not transformed in the twentieth century and it suggests that the development of educational institutions was by and large an elite activity, oriented mostly towards the middle class. When the Muslim elite class imagined their community, the poor scarcely made an impression upon them. These developments in education and the impact of the Khilafat movement resulted, from the 1920s onwards, in increased political activity among Muslims, especially directed by pan-Islamic aspirations. Around the same time in the mid-1920s, the development of the Self-Respect movement drew attention to the significance of their regional identity.