Introduction

Mughal architecture is an amalgamation of Islamic, Persian and Indian architecture. The architecture of the Mughal dynasty reflects their love for poetry, personality and other artistic inclinations. Mughal architecture has its origin in the religion of Islam. The concepts apparent in Islam like power, pleasure and death are reflected in the forts, durbars, mosques, tombs, gardens and so on. The Mughal architecture can be divided into two sections: Early and Later Mughal architecture.

Mughal architecture is an amalgamation of Islamic, Persian and Indian architecture. The architecture of the Mughal dynasty reflects their love for poetry, personality and other artistic inclinations. Mughal architecture has its origin in the religion of Islam. The concepts apparent in Islam like power, pleasure and death are reflected in the forts, durbars, mosques, tombs, gardens and so on. The Mughal architecture can be divided into two sections: Early and Later Mughal architecture.

Features of Mughal Architecture

The features of Mughal architecture includes perfect or near perfect radial or bilateral symmetry, red sandstone with white marble inlays, later pure white marble surfaces, geometric ornament, domes which are slightly pointed instead of hemispherical ones and garden surroundings. In addition to the fine-cut stone masonry used for facades coursed rubble stone construction was used for the majority of walls. For the construction of domes and arches baked brick was also used although this was usually covered with plaster or facing stones. The design of gardens is one of the most important aspects of Mughal architecture which provided the setting for tombs and palaces and also helped for relaxation.

The decoration of the buildings was basically done with ceramic tilework, pietra dura inlay with coloured and semi-precious stones, carved and inlaid stonework. Carved stonework is another interesting feature in the Mughal architecture, ranging from shallow relief depictions of flowers to intricate pierced-marble screens known as jalis. The stone quite often associated with the Mughal architecture is white marble, which can be seen in the magnificence of the Taj Mahal.

The decoration of the buildings was basically done with ceramic tilework, pietra dura inlay with coloured and semi-precious stones, carved and inlaid stonework. Carved stonework is another interesting feature in the Mughal architecture, ranging from shallow relief depictions of flowers to intricate pierced-marble screens known as jalis. The stone quite often associated with the Mughal architecture is white marble, which can be seen in the magnificence of the Taj Mahal.

There is the existence of various influences of the Persian and Hindu architecture in the Mughal architecture. The trabeate stone construction, shallow arches made out of corbels rather than voussoirs and richly ornamented carved piers and columns are some typical Hindu features that have been incorporated in the Mughal architecture. Other constructions like the chhatris- a domed kiosk resting on pillars, chajjas and jarokhas- a projecting balcony supported on corbels with a hood resting on columns became a part of the Mughal characteristics. Extensive use of tilework, the iwan as a central feature in mosques, the charbagh or garden, divided into four and the four-centre point arch and the use of domes are the features borrowed from the Persian architecture.

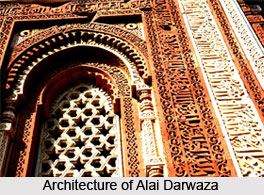

Mughal Architecture that flourished in medieval India can also be termed as the Indo-Islamic architecture. Hindu architecture was modified and elements of spaciousness, immensity and extent were incorporated by the Mughal architecture. The kalash on top of the Hindu temple was borrowed and replaced by a dome and also the Hindu style of decoration used by them for the decoration of their arches. Mughal architecture no doubts occupies a grand position in the history of Indian architecture. Exquisite monuments like the Taj Mahal, Qutub Minar, Alai Darwaza, Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, Vithala temple, Tughlaqabad Fort, Kirti Stambha, FatehpuSikri, Agra Fort, Red Fort etc have glorified India.

Mughal Architecture that flourished in medieval India can also be termed as the Indo-Islamic architecture. Hindu architecture was modified and elements of spaciousness, immensity and extent were incorporated by the Mughal architecture. The kalash on top of the Hindu temple was borrowed and replaced by a dome and also the Hindu style of decoration used by them for the decoration of their arches. Mughal architecture no doubts occupies a grand position in the history of Indian architecture. Exquisite monuments like the Taj Mahal, Qutub Minar, Alai Darwaza, Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, Vithala temple, Tughlaqabad Fort, Kirti Stambha, FatehpuSikri, Agra Fort, Red Fort etc have glorified India.

The Mughal dynasty has gifted India with the premium and the most extravagant architecture and works of art in the overall history of Muslim dynasties. Traces of Mughal architecture can be found in Indian buildings even at present. These buildings have domes and indentures. The empire provided a protected framework or structure for the flourishing of artistic pursuit and the rulers supplied mammoth wealth in these arenas. Even the Mughal rulers were themselves patrons of art and they overpowered all architectural legacies in India. They overawed the people with their power, wealth and charisma. The whole Mughal architecture is a fine combination of so many local and foreign characteristics, which associates it universally with many distinct forms of architecture. These are also a source of inspiration to many other forms of architecture with different cultural background. Prevalence of Mughal architecture has placed India on a global podium making it identifiable to people far and wide.

Characteristics of Mughal Architecture

Characteristics of Mughal Architecture

Perfect or bilateral symmetry, red sandstone with white marble inlays, later pure white marble surfaces, geometric ornament, domes which are slightly pointed instead of hemispherical ones and garden surroundings are the features of Mughal architecture. In addition to the fine-cut stone masonry used for facades, rough rubble stone construction was used for the majority of walls. For the construction of domes and arches baked brick was used that was covered with plaster or facing stones. The design of gardens is one of the most significant aspects of Mughal architecture which provided the setting for tombs and palaces and also helped for relaxation.

Buildings were decorated with ceramic tile work, pietra dura inlay with coloured and semi-precious stones, carved and inlaid stonework. Carved stonework is another interesting feature in the Mughal architecture, ranging from shallow relief depictions of flowers to intricate pierced-marble screens known as jalis.

There is the existence of various influences of the Persian and Hindu architecture in the Mughal architecture. Shallow arches made out of corbels rather than voussoirs and richly ornamented carved piers and columns are some typical features of Hindu architecture that have been incorporated in the Mughal architecture. Other constructions like the chhatris- a domed kiosk resting on pillars, chajjas and jarokhas- a projecting balcony supported on corbels with a hood resting on columns became a part of the Mughal characteristics. Extensive use of tile work, the iwan as a central feature in mosques, the garden, divided into four and the four-centre point arch and the use of domes are the features borrowed from the Persian architecture.

The Mughal Architecture can be termed as the Indo-Islamic architecture. Hindu architecture was modified and elements of spaciousness, immensity and extent were incorporated by the Mughal architecture. The kalash on top of the Hindu temple was borrowed and replaced by a dome. Exquisite monuments like the Taj Mahal, Qutub Minar, Alai Darwaza, Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, Vitthala temple, Tughlaqabad Fort, Kirti Stambha, Fatehpur Sikri, Agra Fort, Red Fort have glorified India.

The Mughal Architecture can be termed as the Indo-Islamic architecture. Hindu architecture was modified and elements of spaciousness, immensity and extent were incorporated by the Mughal architecture. The kalash on top of the Hindu temple was borrowed and replaced by a dome. Exquisite monuments like the Taj Mahal, Qutub Minar, Alai Darwaza, Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, Vitthala temple, Tughlaqabad Fort, Kirti Stambha, Fatehpur Sikri, Agra Fort, Red Fort have glorified India.

The entire Mughal architecture is an excellent combination of various local and foreign characteristics, which associates it universally with many distinct forms of architecture. These are also a source of inspiration to many other forms of architecture with different cultural background.

Early Mughal Architecture

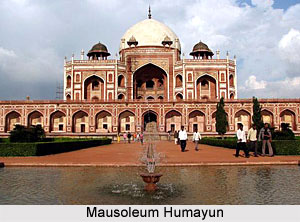

Mughal architecture came into prominence and gained reputation with the rule of Babur who was the first Mughal emperor in India in 1526. Babur`s victory over Ibrahim Lodi, initiated the erection of a mosque at Panipat succeeded by another called the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya. The Maqbara in Vadodara is an example of the early Mughal architecture. Early Mughal architecture relied on post-and-beam construction and scarcely used arches. Some great forts and palaces of the early Mughal period can be traced in the reign of Akbar (1556-1605) in Agra Mausoleum to Humayun is another important signifier of the early architecture of the Mughals.

Later Mughal Architecture

Mughal architecture during the later Mughals is one of a dwindling and pathetic story of culmination and massive downfall and curtain call to one of the most influencing and powerful and respected dynasty in world history, Indeed, as is known from historical records, Mughal Empire, grounded in India by Babur in 1526 A.D., had reached its pinnacle and unprecedented heights and the position was continued unchallenged for several generations down the line, until the death of Aurangzeb. Mughal architecture during the later Mughals and their continuous struggle for authority and their successor states, truly has belittled their regal and imposing ancestors, the binding chains of which were so well established by the once `Mughal Empire`. The historical background to the series of mishaps that had passed through in the interim period, which had resulted in such a dismal state of affairs, will help one understand better regarding the architectural attempts of the later Mughals and their contribution to the illustrious line-up of `Mughal architecture`.

Mughal architecture during the later Mughals is one of a dwindling and pathetic story of culmination and massive downfall and curtain call to one of the most influencing and powerful and respected dynasty in world history, Indeed, as is known from historical records, Mughal Empire, grounded in India by Babur in 1526 A.D., had reached its pinnacle and unprecedented heights and the position was continued unchallenged for several generations down the line, until the death of Aurangzeb. Mughal architecture during the later Mughals and their continuous struggle for authority and their successor states, truly has belittled their regal and imposing ancestors, the binding chains of which were so well established by the once `Mughal Empire`. The historical background to the series of mishaps that had passed through in the interim period, which had resulted in such a dismal state of affairs, will help one understand better regarding the architectural attempts of the later Mughals and their contribution to the illustrious line-up of `Mughal architecture`.

Emperor Aurangzeb had breathed his last in 1707, but the Mughal Empire endured, at least officially, for another 150 years. It lasted until the British exiled and imprisoned the last Mughal ruler after the historic uprising of Sepoy Mutiny in 1857. Shah Alam Bahadur Shah I had succeeded Aurangzeb in 1707. As the empire weakened the nawabs of Murshidabad, Awadh and Hyderabad established their own successor states, whereas, Sikh, Jat, Maratha and other Hindu rulers asserted their independence; carving out numerous little kingdoms from what once had been a single empire. And herein itself comes the domain of the so-called Mughal architecture during the later Mughals and the difference that they owned with their predecessors and the likeness they were to bear with these independent small `princely states`. The architecture sponsored by the rulers and inhabitants of these new domains was heavily dependent on the Mughal style established during Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, yet in each case new formal interpretations and meaning are given to older forms. The results were often highly creative expressions, reflecting these houses` political allegiance and religious affiliation. And a strict `Mughal-ish` architecture under later Mughal rulers, as can be comprehended, was endeavoured to be begun in the still regaining majestic Delhi of Akbar or Shah Jahan; Delhi always had played significant roles during the Mughal Empire, which was much later transformed into a British Delhi of present times.

From the time Shah Alam Bahadur Shah I had succeeded Aurangzeb, he never entered Delhi. He did, however, commission the construction of a mosque and his own simple screened yet roofless tomb in the dargah of Bakhtiyar Kaki, just behind the historic and gigantic 13th century Qutb Minar. The continued importance of this dargah is attested by buildings provided there by some of Bahadur Shah I`s successors and the fact that the last Mughal resided in a mansion attached to the dargah. Qutb Sahib Bakhtiyar Kaki, a follower of the Chishti order, had been a 14th century saint. His dargah was a venerated shrine even before his demise, though never as popular as the dargah of Shaikh Nizam ud-Din, also in Delhi.

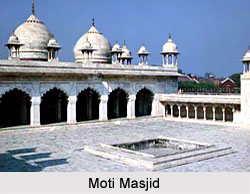

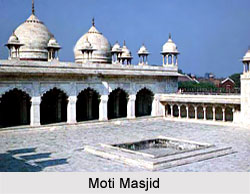

Shah Alam Bahadur Shah I`s mosque, adjacent to his tomb at the shrine of Bakhtiyar Kaki, is acknowledged today as the Moti mosque. Probably built several years before Bahadur Shah I`s death in 1712, the marble mosque is situated in a walled enclosure to the west of the saint`s grave. Unlike the double-aisled Moti masjid in the Shahjahanabad fort (Red Fort), this is a single-aisled structure. Shah Alam`s Moti masjid is surmounted by three bulbous domes on constricted necks. On each corner of the east central bay can be witnessed a slender engaged baluster-like column, a feature by now used in religious architecture.

Shah Alam Bahadur Shah I`s successor, Farrukh Siyar (r. 1713-19), further had embellished the dargah by building a screened marble enclosure around Bakhtiyar Kaki`s grave and two marble entrance gates leading to the grave site. He also had rebuilt in white marble the dargah`s original stucco mosque situated to the east of the saint`s tomb. The marble gates are inscribed with inlaid black marble characters, thus drawing upon forms and materials, first introduced by Shah Jahan at the Ajmer Chishti shrine. The one closest to the tomb, dated 1717-18, is characterised by rounded cusped arches in whose spandrels are large floral medallions and arabesque creepers. Beyond Farrukh Siyar`s gates the devotee goes through a series of passages from the first entrance to the grave. This Mughal architectural complexity under the later Mughal works emphasise the saint`s importance. Since dargahs have inherent authority, the later Mughals, as a result of their patronage, drew upon that authority.

Farrukh Siyar`s additions radically had changed the shrine`s appearance. Visually the Chishti dargah of Bakhtiyar Kaki now more closely resembled the premier Chishti shrine of Muin ud-Din in Ajmer, where during Shah Jahan`s reign, many of the major structures had been built by the royal family. But the shrine in Ajmer had received no new support from the late Mughals due to unfavourable political conditions. Instead Bakhtiyar Kaki`s shrine was revitalised by the later Mughals in white marble and building types that evoked a glorious Mughal past. This again brings to surface the dwindling political and economical condition of the later Mughal Dynasty, the result of which was a terribly painful suffering of Mughal architecture. Mughal architecture during and under the later Mughals was such that they could not move much beyond Delhi, owing to such financial and hostile instability of their reign.

Muhammad Shah had assumed the throne during late 1719, reigning twenty-nine years, until his death in 1748. He was the third monarch to rule after Farrukh Siyar; his two predecessors did not survive even a full year. Muhammad Shah is credited with constructing a wall around Dargah Chiraq-i Delhi in 1729 and the construction of a wooden mosque inside the Shahjahanabad palace. He also had erected his own tomb inside the shrine of Nizam ud-Din in Delhi. This white marble screened tomb is modelled closely on the nearby tomb of Jahan Ara Begum, although this tomb-type long had become standard. Muhammad Shah`s enclosure reveals more profuse floral ornamentation and highly carved surfaces, for instance, along the screen`s base.

Muhammad Shah had assumed the throne during late 1719, reigning twenty-nine years, until his death in 1748. He was the third monarch to rule after Farrukh Siyar; his two predecessors did not survive even a full year. Muhammad Shah is credited with constructing a wall around Dargah Chiraq-i Delhi in 1729 and the construction of a wooden mosque inside the Shahjahanabad palace. He also had erected his own tomb inside the shrine of Nizam ud-Din in Delhi. This white marble screened tomb is modelled closely on the nearby tomb of Jahan Ara Begum, although this tomb-type long had become standard. Muhammad Shah`s enclosure reveals more profuse floral ornamentation and highly carved surfaces, for instance, along the screen`s base.

It is only commencing with Muhammad Shah`s reign that considerable building activity is witnessed again within the walled city of Shahjahanabad, an interim of respite for Mughal architecture during later Mughals indeed! Significant construction occurred both before and after the invasion of Delhi by the Iranian Nadir Shah in 1739, suggesting that his attack had less devastating long-term effects than is commonly believed. Among the structures erected before Nadir Shah`s invasions is the Sunahri or Golden mosque built in 1721-22 by Raushan ud-Daula, who had provided lavish celebrations at the Urs ceremony of Bakhtiyar Kaki. This three-bayed single-aisled mosque is situated next to the Mughal police station (still in use today) in Chandni Chowk, then across from Jahan Ara`s momumental serai. The mosque was provided at the beginning of Raushan ud-Daula`s rise to power. The location alone, close to the principal entryway of the Shahjahanabad palace, indicates his close ties to the emperor. An inscription over the structure`s east facade indicates that the mosque was erected to honour Shah Bhik, his spiritual mentor, who had died two years earlier.

Reached by a flight of narrow steps, the structure is elevated above the ground. The Sunahri mosque`s slender minarets that rise above the roof line and the gilt metal-plated bulbous domes resting on constricted drums, had instilled a delicate air to Shahjahanabad`s skyline. The emphasis during this time was on delicacy and refinement, not just on the sense of awesome height that had been a major factor in late 17th century Mughal taste. Muhammad Shah`s reign was truly like a breath of fresh air for Mughal architecture under later Mughals, which at times possessed its distinctiveness, as can be noted.

Although Raushan ud-Daula had provided more buildings than any other noble during Muhammad Shah`s reign, his was not the finest in Delhi. That superb building is the Fakhr al-Masjid, or `Pride of the Mosques`, provided by a noblewoman. The mosque was built in 1728-29 by Kaniz-i Fatima, entitled Fakhr-i Jahan (Pride of the World), to commemorate her deceased husband, Shujaat Khan, a high-ranking noble under Aurangzeb. Situated on an elevated plinth, not far from Delhi`s Kashmir Gate, it is one of the few stone mosques built in Delhi during the 18th and 19th centuries. This red sandstone mosque, faced with white marble, is clearly modelled on the major mosques of the city erected during the reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. Most of those mosques, too, had been provided by the court ladies. Fakhr-i Jahan, by erecting this mosque, merely had continued an earlier tradition. While the emphasis on the mosque`s height due to its tall minarets is archetypal of the period, the delicate inlay and carved niches of its interior recall the uncluttered aesthetic of Shah Jahan`s earlier religious architecture. Mughal architecture under the supremacy of the later Mughals was thus, in very many occasions, supremely endorsed by noblemen and women, most of whom possessed intimate associations with the once shining Mughal throne.

Other notable mosques of Muhammad Shah`s reign built inside Delhi before Nadir Shah`s invasion display the continued vitality of the evolving Mughal architectural style under later Mughals, one that persisted even in the absence of strong central leadership. These include the mosque and school of Nawab Sharaf ud-Daula, dated 1722-23 and the Muhtasib`s mosque provided in 1723-24 by Abu Said, the hereditary inquisitor (muhtasib) of Delhi. Both of these are single-aisled three-bayed mosques, entered through openings with cusped arches and surmounted by bulbous ribbed domes. These domes recall those on the Moti mosque at Bakhtiyar Kaki`s dargah and are similar to many during this period. Nawab Sharaf ud-Daula`s mosque is situated on an elevated plinth with chambers beneath, that may have served as the school. The mosque of Abu Said rather unusually for this time, is not however placed atop a high plinth. Unlike Sharaf ud-Daula`s solid appearing edifice, the latter bears delicate stucco ornament, similar to that on Raushan ud-Daula`s mosque built only two years earlier.

Religious structures appear to dominate the later Mughal architecture of Delhi. That is because mostly sacred buildings remain, although serais, gardens and markets continued to be erected. The surviving ones are outside the city wall. For instance, an extensive bazaar recognised today as the Tripolia with a massive triple-arched entrance gate at either end was built in 1728-29, north of the walled city along the major highway leading to Lahore. This compound was built by Nazir Mahaldar Khan, superintendent of the women`s quarter in the palace of Muhammad Shah.

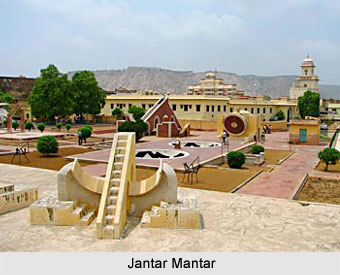

At Muhammad Shah`s request, the raja of Jaipur, Sawai Jai Singh Kachhwaha (1699-1743), had provided Delhi with an extraordinary observatory acknowledged as the historic Jantar Mantar. This able statesman and astrologer had constructed the observatory in approximately 1725 in an area to the south of the walled city, known as Jaisinghpura. Subsequently, Sawai Jai Singh had built similar observatories with comparable sophisticated structural instruments in Jaipur, Benaras, Mathura and Ujjain. Constructed of brick and plaster, the juxtaposed circular and angular shapes of these enormous instruments produce an effect unlike that of any other Mughal architecture of the period under the later Mughals. Their forms as well as their scientific sophistication remain appealing to 20th century sensibilities. Muhammad Shah`s desire for such an observatory speaks highly of his interest in promoting scientific knowledge, not simply the literary arts for which he is well known. It might also have been due to Muhammad Shah`s endeavours that his still later successors had strove to instill some beautification into the farther places from Delhi, like in Rajasthan or in Bihar. As such, architecture of Rajasthan during later Mughals, architecture of Agra during later Mughals, architecture of Varanasi during later Mughals and, architecture of Bihar during later Mughals, had been victorious to enlist their names in the domain of Mughal Indian history.

Mughal Architecture during Akbar`s reign

Mughal architecture gained prominence during the rule of Akbar. He built massively and the style was unique. Most of Akbar`s buildings are in red sandstone, exempted at times through marble inlay. Fatehpur Sikri which is located 26 miles west of Agra. Mausoleum was constructed in the late 1500s and bears the testimony to the era of his royal heritage. In Gujarat and many other places we find the presence of a style, which is a blend of Muslim and Hindu characteristic features of architecture. The great mosque is one such epitome of architectural brilliance unmatched in elegance and splendour. The south gateway is well known, excelling any similar entrance in India in its size and structure. The Tomb of Humayun and tomb of Akbar at Sikandrabad are some finest work of architectural magnificence which highlights the Mughal architecture prototypes. The tomb situated in a garden at Delhi, has an intricate ground plan with central octagonal chambers, which is joined by an elegantly facade archway, surmounted by cupolas, kiosks.

Mughal Architecture during Jahangir`s reign

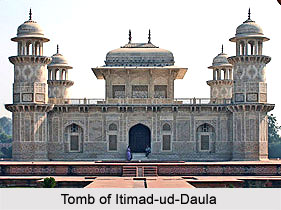

During the reign of Jahangir from 1605- 1627, the decline in the Hindu influence on Mughal architecture was witnessed. His style was Persian like his great mosque at Lahore, which is covered Tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulawith enamelled tiles. Akbar`s mausoleum was built during his rule. "Verinag" and "Chashma-Shahi" are gardens built by Jahangir beautifully around spring. The tomb of Itimad-ud-Daula completed in 1628, was built entirely of white marble and covered wholly by pietra dura mosaic. The Shalimar Gardens and other pavilions on the shore of Kashmir`s Dal lake was also built by him. The Shalimar garden is also his creation that is distinguished by a series of pavilions on carved pillars, surrounded by pools with seats which can be reached by stepping stones. Jahangir was responsible for the development of the Mughal garden. Jahangir`s own tomb has no dome, minarets and ornamentation are only evident. The extensive use of white marble as a material and inlay as a decorative motif were the two major innovations that were introduced by the Mughals.

During the reign of Jahangir from 1605- 1627, the decline in the Hindu influence on Mughal architecture was witnessed. His style was Persian like his great mosque at Lahore, which is covered Tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulawith enamelled tiles. Akbar`s mausoleum was built during his rule. "Verinag" and "Chashma-Shahi" are gardens built by Jahangir beautifully around spring. The tomb of Itimad-ud-Daula completed in 1628, was built entirely of white marble and covered wholly by pietra dura mosaic. The Shalimar Gardens and other pavilions on the shore of Kashmir`s Dal lake was also built by him. The Shalimar garden is also his creation that is distinguished by a series of pavilions on carved pillars, surrounded by pools with seats which can be reached by stepping stones. Jahangir was responsible for the development of the Mughal garden. Jahangir`s own tomb has no dome, minarets and ornamentation are only evident. The extensive use of white marble as a material and inlay as a decorative motif were the two major innovations that were introduced by the Mughals.

Mughal Architecture during Shah Jahan`s reign

Mughal architecture attained its perfection in the construction of Jama Masjid of Delhi during the rule of Shah Jahan. Humayun`s tomb was the first of the tombs, which continued the saga of the succession of tombs out of which the Taj Mahal is a magnificent piece of art. The Red Fort contains the imperial Mughal Palace, which is situated in Delhi. Marble was used for the constructions. In the palace fort of Agra, Shah Jahan replaced old structures along as well as built a couple of new ones. An inlay of black marbles was used for the re-building of The Diwan-I-Am. The Moti Masjid is another beautiful creation which was built during his rule. The Pearl Mosque of Agra is reminiscent of the style that was eminent in Mughal era. Shah Jahan built a new capital, Shahjahanabad, with its magnificent Red Fort. The Hall of Public Audience, in the fort contains the Peacock Throne, which consists of jewels and precious metals and stones. It took ten years to build the city. It has three mosques that have survived the ravages of time.

Sources Of Mughal Architecture

The 16th and the 17th centuries brought immense changes in India. By then it was the turn of the Mughal Empire to rule over India and they brought with them the Oriental charm of Persian art, Islamic architecture and an impressive ethos that was going to be a part of the sub-continent forever. Their reign was marked by several beneficial administrative policies and unprecedented development in the fields of art and culture. One of the greatest gifts of the Mughal dynasty to India was the architecture that flourished under the secured framework of this empire. In fact, the primary sources of Mughal architecture lay in the Islamic and native Hindu styles. Mughal architectural taste and idiom evolved from the center outwards. It was prompted by imperial predilection, rarely arbitrary but embedded in political and cultural ideology.

The 16th and the 17th centuries brought immense changes in India. By then it was the turn of the Mughal Empire to rule over India and they brought with them the Oriental charm of Persian art, Islamic architecture and an impressive ethos that was going to be a part of the sub-continent forever. Their reign was marked by several beneficial administrative policies and unprecedented development in the fields of art and culture. One of the greatest gifts of the Mughal dynasty to India was the architecture that flourished under the secured framework of this empire. In fact, the primary sources of Mughal architecture lay in the Islamic and native Hindu styles. Mughal architectural taste and idiom evolved from the center outwards. It was prompted by imperial predilection, rarely arbitrary but embedded in political and cultural ideology.

Unlike the other dominant Islamic rulers of Iran and Turkey, the Safavids and Ottomans, the Mughals ruled a land dominated by non-Muslims, largely Hindus. They adopted a policy of tolerance towards the indigenous religions and traditions. In many cases these were even respected by the Mughal rulers. This fact becomes more evident from their patronage of the arts, literature and music that comprised many indigenous elements. Over their 300-year rule, Mughal attitudes toward the native Indian population - Hindu and Muslim - varied; so did Mughal adaptation of earlier Indian art forms. During the earliest days of the Mughal patronage, little attention was paid to India`s non-Islamic architectural traditions; however, during the reign of the third Mughal ruler, Akbar (1556-1605), indigenous Indian elements, both Hindu and Muslim, were incorporated into the Mughal structures.

Mughal architecture was, thus, the result of innovative genius that borrowed from Indian, Timurid and even European sources. The Mughal artists interpreted these borrowed forms, both in terms of symbolism and style, to their own purposes. However, it goes without saying that the Mughal architecture owes its Islamic sources to the other Muslim dynasties as well: the Delhi Sultanate, the Khaljis, the Tughlaqs, the Lodhis, the Sayyids and the Surs. The Slave Dynasty laid the foundation of Islamic architecture in India. The initial monuments that were built by following the Islamic style were primarily mosques. In 1192, Qutb ud-Din Aibak, a military commander of the Afghan Ghori dynasty, defeated the last Hindu ruler of Delhi. Within a few years, a great deal of north India was under Ghori control, and in 1206 Aibak asserted his independence from the Ghoris, declaring himself sultan of India. He and his successors built architecture that served as one foundation of Mughal art.

Aibak`s first mosque, significantly now called the Quwwat al-Islam or Might of Islam, was erected in Delhi, the capital of the new Muslim. Calligraphy and verses from the Quran were used to embellish the prayer chambers. Later the Mughal architecture also followed this style. Mughal monuments like the Jama mosques and the Taj Mahal display these characteristics. With passing time the architectural motifs used in Islamic architecture were chosen from the indigenous culture. Motifs, such as the parrot, mangoes and flowers only found in India to supplement Persianate imagery, such as cedars and tulips, alien to the subcontinent. Many motifs - architectural and literary - had no strictly sectarian connotation. To call a motif Hindu or Muslim has little meaning, for elements such as the lotus or even trabeated architecture, still found in parts of Ala ud-Din`s extension to the Quwwat al-Islam mosque, are now part of a well-established architectural tradition developed under the Indian sultans. Apart from these the tombs were also erected by following the Persian and Islamic idioms.

Aibak`s first mosque, significantly now called the Quwwat al-Islam or Might of Islam, was erected in Delhi, the capital of the new Muslim. Calligraphy and verses from the Quran were used to embellish the prayer chambers. Later the Mughal architecture also followed this style. Mughal monuments like the Jama mosques and the Taj Mahal display these characteristics. With passing time the architectural motifs used in Islamic architecture were chosen from the indigenous culture. Motifs, such as the parrot, mangoes and flowers only found in India to supplement Persianate imagery, such as cedars and tulips, alien to the subcontinent. Many motifs - architectural and literary - had no strictly sectarian connotation. To call a motif Hindu or Muslim has little meaning, for elements such as the lotus or even trabeated architecture, still found in parts of Ala ud-Din`s extension to the Quwwat al-Islam mosque, are now part of a well-established architectural tradition developed under the Indian sultans. Apart from these the tombs were also erected by following the Persian and Islamic idioms.

However, Mughal architecture also owes its sources to the native Indian style. The handsome uses of jharokhas, chhatris, chajjas, torana motifs, etc mirror a direct influence of the indigenous architectural style. These elements are regular features of Rajput buildings. Mughal buildings, such as the palaces built by Akbar, the Red Fort and others reflect the Hindu influence despite the use of Islamic architectural prototypes. Such amalgamations were one of the obvious reasons why the Mughal Architecture was also known as the Indo-Islamic architecture. The recurrent Hindu features in the Mughal constructions included the balconies, half domed double portals, decorative brackets, ornate decorations, minars, etc.

Although the Mughal architecture borrowed heavily from different styles but it was successful in reshaping the art and architecture of India. In fact, come of the most grandiose and magnificent Indian monuments were built under the Mughal reign. Moreover, with such incorporation of different sources, the Mughal style eventually came to represent not Mughal authority, but the cultural and social values established under the Mughals.

Islamic Sources of Mughal Architecture

Mughal architecture and its wondrous brilliance as can be witnessed in the present times, is indisputably the most sublime, the most lofty, the most elaborate of all architectural wonders that have ever arrived to India. Truly, Mughal architecture is the ideal instance of par excellence in India. As such, a question might just arise to the admirer`s mind, as to from which precise source did these brilliant men derive such unforgettable plannings that one still gets to view in its original form. As such, the Islamic sources of Mughal architecture can be regarded as the most stellar and incandescent of the said emperors, who have time and again borrowed potential influences from their Islamic predecessors to chisel masterpieces. The precise Islamic sources of Mughal architecture are committed by historians to the very initial Muslim rulers, who had arrived to India, heavily saturated with their Arabian, Persian or Iranian charms.

The Delhi Sultanate, beginning their rule in 1192, was the first to keep a footstep unto India, with the motley of ruling dynasties to arrive, regarded as the inaugural Islamic source to Mughal architecture. Among the earliest persisting Islamic monuments in India (referring to the erstwhile Undivided Indian territory, prior to 1947) are the foundations of the walled city and mosque at Banbhore near Thatta in Sind, presently in Pakistan. The site was embarked soon after the birth of Islam and is tenably the earliest Arab settlement in the South Asian continent. Other remains hinting at an early Islamic source to Mughal architecture is the presence of a tomb dated to the mid-12th century, discovered at Bhadreshvar in the coastal regions of Gujarat in western India. Another aspect of Islamic presence were the sporadic invasions, more `destructive` than `constructive`, intended to plunder valuables and not to fabricate any record of a permanent presence. The incursions into India made by Mahmud of Ghazni during the 11th century exactly falls into this category. However, in 1192, Qutb Ud Din Aibak, a military commander of the Afghan Ghorid Dynasty had overpowered the last Hindu ruler of Delhi. Within a few years, an enormous section of north India was under Ghorid control. In 1206, Qutb Ud Din Aibak had cleverly asserted his independence from the Ghorids, declaring himself Sultan of India. He and his successors had thus erected architecture that served as one foundation of Mughal art.

Among the foremost concerns of the `conqueror` (referring to Qutb Ud Din Aibak) was the construction of a congregational `Jami` mosque. This move was looked as obligatory for the legitimisation of the sultan in this newly-acquired territory, as well as for the validation and spread of Islam. Qutb Ud Din Aibak`s first-ever mosque, appreciably now named the Quwwat al-Islam or Might of Islam, was chiselled in Delhi, the capital of the new Muslim rulers. Constructed from the architectural appendages of temples, believed to also serve as the first of the Islamic sources of Mughal architecture, the mosque in its first phases emerges to be modelled loosely on a common form of Ghond-penod mosques. Such mosques, espousing a general Iranian fashion, possessed a central open courtyard surrounded by cloistered halls on three sides; the prayer chamber was built on the fourth side. Each side further possessed a central vaulted entrance or aiwan. Hence, such mosques are acknowledged as four-aiwan types. In India, their outlook is somewhat modified and by the Mughal period the term aiwan had donned a different meaning. During this very early period, the mosque entrances were not vaulted. The prayer chamber was placed on the west, the side that in India faces Mecca - thus answering for the direction toward which all Indian mosques are oriented since. Variances of this Iranian four-aiwan plan continued to be constructed even through the Mughal period, which truly had served as most authentic Islamic sources to Mughal architecture.

This inclination toward intense patterning over a whole stone-carved surface reappears in the early phases of Mughal architecture, which had heavily relied on sources of their preceding Islamic dynasties. Bountiful surface decoration is characteristic of much Islamic ornamentation, in both India and abroad.

The subcontinent`s first monumental Islamic tombs were built under Iltutmish, which later on was to impact profoundly upon Mughal architecture and its Islamic sources. One, for instance, recognised today as the Sultan Ghari tomb, was constructed for his son and a second was erected for himself - both in Delhi. The interior of Iltutmish`s own square-planned tomb was fancified in a fashion similar to his screen at the Quwwat al-Islam mosque.

No major Islamic structures remain in India that date between the death of Iltutmish in 1235 and the beginning of the 14th century. However, under the Khilji Sultan Ala ud-din (ruling period 1296-1316), Indo-Islamic architecture had assumed supreme regenerated importance. Concentrating upon the monument that had persisted symbolically paramount, Ala-ud-din Khilji had begun expanding the Quwwat al-Islam mosque to triple its initial size. However, the project was never completed. In fact, the only remaining parts of the Khilji addition to the Quwwat al-Islam mosque complex are an enormous unfinished minaret, pillared galleries and an entrance portal on the south, known universally as the Alai Darwaza. Dated back to 1311, numerous epigraphs on this gate are interestingly not Quranic, rather hyperbolically praising its patron, Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji. Although it is not a monumental structure, it is one that later builders, including the early Mughals, looked upon as a tremendous Islamic source of inspiration for Mughal architecture.

By the Khilji period, Indo-Islamic culture had come into its own identity. Underscoring this was the then contemporary works of Amir Khusro, still weighed as one of the greatest Indian poets. Writing in Persian, the official language of most Muslim courts and kings in India, Khusro had utilised motifs such as the parrot, mangoes and flowers. And basing their architectural works on the matchless Amir Khusro, the Mughals had drawn heavily to influence them, later looked as most convincing Islamic sources for Mughal architecture. These motifs were then only found in India which could indeed supplement `Persianate` imagery, such as cedars and tulips, completely alien to the Indian subcontinent. By this period, umpteen motifs - architectural and literary - possessed no strictly sectarian implication. To call a motif Hindu or Muslim possessed little meaning, because elements such as the lotus or even trabeated architecture, still found in parts of Ala-ud-din`s extension to the Quwwat al-Islam mosque, are now part of a well-established architectural tradition developed under the Indian sultans.

Following the Khiljis under the Delhi Sultanate Islamic source for Mughal architecture, the Tughlaq Dynasty had emerged as the ruling power. Taking over control in 1320 over an area that included much of the Indian subcontinent, their territory quickly weakened as provincial governors avowed independence from central authority, leaving them little more than Delhi and its suburbias. While the dynasty survived only in name until 1412, Delhi was sacked in 1399 by the invasion of Timur, the legendary ancestor of the Mughals.

The Tughlaqs were however inexhaustible providers of architecture, especially under the third ruler, Feroz Shah Tughlaq (r. 1351-88), whose extensive building campaigns were in a sense a `cover` for his politically weak regime. In general, architecture under the Tughlaqs had become increasingly austere into the 14th century. For instance, richly carved stone facades and interiors were replaced with plain stucco veneers and Quranic inscriptions rarely ornamented any structure. While Tughlaq buildings may have been painted, yet, multi-coloured stones on their surface were exceedingly infrequent.

The Mughals subsequently banked on Islamic sources heavily for their architectural wonders. And just like their Tughlaq predecessors, Mughals too provided support for the welfare of all subjects. For instance, the Tughlaq sultans and nobles had endowed the Hindu temples. A likewise movement was also noticed under the Mughal dynasty, who had voraciously patronaged and provided for Hindu monuments.

The most dramatic illustrations of distinctly regional style are found in the architectural traditions of Bengal and Gujarat. In Bengal, the cast of the village hut with its sloping roof, well suited for heavy rains, was adapted for tombs and mosques, for example, the Eklakhi tomb in Pandua, West Bengal, dateable to the 15th century. Probably the curved roof was used in palatial architecture as well, but sadly there exists no such surviving examples. Such Islamic sources were very common in Mughal architecture, commencing around the mid-17th century. Such roofs were referred to as bangala in Mughal documents and were often employed by the end of the 17th century far from Bengal in Mughal architecture.

In Gujarat, as in Bengal, architecture under the newly established Ahmad Shahi dynasty (1408-1578) acquired a distinctly regional character. Features found commonly on tombs, mosques and saints` shrines (dargahs) include ones such as serpentine-like gateways (toranas) or lintels above prayer niches (mihrabs), bell-and-chain motifs chipped upon pillars and walls, pillars supporting corbelled domes and ceiling insets and carved panels often depicting trees. All of these singular carvings were brilliantly ultimately derived from Gujarati temple traditions. Such an uncanny amalgamation of influences was very much evident in the creations of Emperor Akbar, considered inimitable Islamic sources of Mughal architecture.

After some hundred years, during which Delhi had enjoyed little prestige, the Afghan-descended Lodi dynasty (1451-1526) had endeavoured vigorous efforts to revitalise the city`s status. They had vanquished their enemies, the Sharqis of Jaunpur and soon afterwards, commenced extensive building in Delhi itself. Particular motifs on Lodi buildings are identical to those witnessed earlier only at Jaunpur. This is the case, for instance, with engaged colonettes beautified with an interwoven pattern on the Bara Gumbad. This intimates that artists were taken to Delhi from Jaunpur, in an attempt to revive the prestige of the traditional capital. The revitalisation of Delhi was accelerated under the reigns of the first two Mughals - Babur and Humayun, who had eventually succeeded the Lodis, bringing an end to the Delhi Sultanate. The Delhi Sultanate was the most stellar instance of abundant Islamic source for Mughal architecture. Following the reigns of Babur and Humayun, however, Mughal authority in India was briefly interrupted when the Delhi throne was arrogated in 1540 by the Afghan ruler, Sher Shah Suri and his successors (1538-55). Although fifteen years of Mughal rule separated the periods of Lodi and Suri authority, the architecture produced under these two Afghan dynasties are mostly discussed simultaneously, due to their closeness of influence in form and spirit.

The dominant themes of Mughal art accompanied with the all pervading presence of geometry were indeed a direct influence of Islamic architecture. Whether in a mosque or a bejewelled mirror-back it is the clever use of the arabesque pattern to achieve patterns of dizzying complexity the Mughal architecture echoes the Islamic influence. The relatively austere yet sublime effect of calligraphy on buildings or on manuscript pages; the preponderance of flowers in all manner of stone or cloth or metal signifying the omnipresence of the omnipotent once again establishes the Islamic influence in Mughal architecture. The lofty ornamentation; and the frequent appearance of animals and birds in Mughal architecture still stand as a proof of serving as a bridge of Islamic source to subsequent Mughal architectural ornamentation.

Non-Islamic Sources of Mughal Architecture

Mughal architecture seizes its inspirational and par excellence position in the world history, with its gigantic, mammoth-like, exquisite, awing, durable and incredibly unbelievable structures. The Mughals are known to have been heavily influenced from both Islamic and non-Islamic sources while building those motivating pieces in India. The non-Islamic sources of Mughal architecture have been strewn with perfection from those Hindu temple or fortress wonders, lying hidden in the outlands or wildernesses of any given region.

Mughal emperors have always diversified their architectural beauties, concentrating first in the centre, fanning out towards diversification. Architectures have been triggered by imperial penchant, rarely capricious, but engrafted in political and cultural ideology. It has always so happened that any given ruler is not often exclusively responsible for construction outside central urban areas; on the other hand, it is the nobility, mostly high-ranking, wealthy and refined and the chic, who are responsible for building in such places. This group of `nobility` had often extravagantly, erected, on their landholdings that were granted in place of salary, even though these lands were shifted approximately every two years to prevent the establishment of menacing or intimidating power bases. And this very factor had heavily impressed upon the non-Islamic sources of Mughal architecture, with most of the noble sections, coming from a Hindu household.

The non-Islamic sources of Mughal architecture began to mostly flourish around the period of 1300 A.D. and possibly culminating in 1500 A.D as Hindu and Jain architecture continued to be erected in north India during this time. For instance, at least three temples in Bihar are either dated or dateable to the Delhi Sultanate period. One of them, in the Hindu pilgrimage city of Gaya, even assumes an inscription extolling the Muslim overlord, Feroz Shah Tughlaq from Tughlaq Dynasty, a ruler conventionally deemed to be hostilely anti-Hindu. Some temples of this period can be witnessed to be of a domed strategy, as designated by paintings illustrating a 1516 Aryanyakaparvan. As such, domed architecture cannot be considered exclusive to the Muslims, but, with proper non-Islamic referential sources under Mughal architectural shadow.

`Secular architecture` constructed also during this time under Hindu patrons, has had a satisfying impact upon subsequent secular buildings, notably those of the Mughals. One such instance of non-Islamic source in Mughal architecture, a magnificent one, is the Man Mandir palace built in Gwalior, approximately in 1500 A.D. by Raja Man Singh Tomar. Amongst the few buildings admired by Babur in India, the palace is rightly regarded as having influenced Akbar during the designing of his own palaces. Positioned atop the high flat plateau of the ancient Gwalior fort, the palace`s facade is marked with a series of circular buttresses, each surmounted by a high domed chattri and the facade is ornamented with tiles, glazed predominantly in blue or yellow. While the Gwalior palace`s exterior had influenced the inlaid mosaic facade of the Delhi Gate in Akbar`s Agra Fort, the interior of this palace bore an even greater impact of Non Islamic source on Akbar`s architecture. Like subsequent Mughal palaces, the Gwalior palace, always considered a significant non-Islamic source to Mughal architecture, have made excellent use of animal brackets supporting the gallery eaves (chajjas). These chajjas probably were ultimately modelled upon torana motifs that have been skillfully utilised both as wall ornamentation as well as operative and useable devices. While Man Singh`s `Hindu palace`, not far from Agra and Fatehpur Sikri, had an apparent impact on Islamic `Akbari architecture`, it is also wrong to deem the Gwalior palace uniquely Hindu in form. On the other hand, it belongs to a type of domestic non-Islamic architecture that late during the Delhi Sultanate period was verily utilised by both Hindus and non-Hindus.