Babur had begun his Mughal Empire upon a very Oriental India in 1526 A.D., after much fanfare and hardship amidst antagonisms of the Delhi Sultanate rule and other opponents, from whom he was astute enough to snatch away and establish a realm. After the brilliant ascendancy of this very first Mughal ruler, time had come for him to yield place for his upcoming generations, in the form of his son, Humayun, the second in line to the Mughal throne. Though not much like his illustrious father, Mughal architecture during Humayun also had its share of individuality and distinctness. With the exception of a single inscribed mosque in Agra, no other surviving structure indubitably had resulted from Humayun`s patronage.

Babur had begun his Mughal Empire upon a very Oriental India in 1526 A.D., after much fanfare and hardship amidst antagonisms of the Delhi Sultanate rule and other opponents, from whom he was astute enough to snatch away and establish a realm. After the brilliant ascendancy of this very first Mughal ruler, time had come for him to yield place for his upcoming generations, in the form of his son, Humayun, the second in line to the Mughal throne. Though not much like his illustrious father, Mughal architecture during Humayun also had its share of individuality and distinctness. With the exception of a single inscribed mosque in Agra, no other surviving structure indubitably had resulted from Humayun`s patronage.

Despite the paucity of remaining buildings from Humayun`s time, contemporary sources refer to his architectural output. They describe, for instance, his unique conceptions, although they are based on Timurid design concepts. One of them was an unusual and almost unseen `floating palace`, formed from four barges, each bearing an inward facing arch and attached in such a manner that an octagonal pool formed the central portion. In addition, Humayun is also known to have designed three-storied collapsible palaces, gilded and domed. More traditional palaces were constructed at Gwalior, Agra and Delhi. Neither the Gwalior palace, constructed of chiselled stones, nor the multi-stoned Agra palace, with its octagonal tank, connected by means of subterranean passages to other parts of the palaces, survives for admirers to admire in detail!

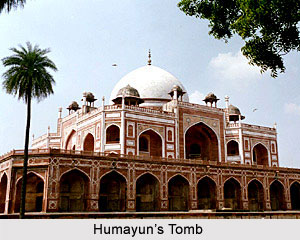

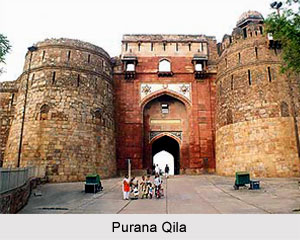

It is however enlightened that Humayun had commenced a walled city and imperial palace on the site of Purana Qila in 1533. The city, named Din-Panah or Refuge of Religion, was auspiciously situated upon the age-old legendary site recognised as Indraprastha, long associated with the traditional Hindu epic Mahabharata. The city was also located in very close proximity to the shrine of Delhi`s most revered saint, Nizam al-Din Auliya. The choice of the site must have been made with its history in mind, because Mughal architecture under Humayun, superstitious yet religious, had sought advice from learned men as well as astrologers. Even after Humayun`s victorious return to India in 1555, this site remained symbolic for the Mughals, for, Humayun`s Tomb was constructed in this same area.

It is however enlightened that Humayun had commenced a walled city and imperial palace on the site of Purana Qila in 1533. The city, named Din-Panah or Refuge of Religion, was auspiciously situated upon the age-old legendary site recognised as Indraprastha, long associated with the traditional Hindu epic Mahabharata. The city was also located in very close proximity to the shrine of Delhi`s most revered saint, Nizam al-Din Auliya. The choice of the site must have been made with its history in mind, because Mughal architecture under Humayun, superstitious yet religious, had sought advice from learned men as well as astrologers. Even after Humayun`s victorious return to India in 1555, this site remained symbolic for the Mughals, for, Humayun`s Tomb was constructed in this same area.

Khwand Amir, a noble in Humayun`s court, reports that by 1534 the "walls, bastions, ramparts and gates" of Humayun`s Din-Panah were almost wrapped up, adding that it was hoped that the "great and lofty buildings" of the city soon would be finished. It is yet again difficult to state from Khwand Amir`s verbose prose exactly how much of the city in reality was ready by 1534. Humayun`s dream of Mughal architectural beauties had only remained in his dreams due to his constant engagements with Sher Shah Suri and guaranteeing his central Delhi throne. Mughal architecture during a much wobbly Humayun states that, almost certainly he had built the fort`s small octagonal pavilion, acknowledged as the Sher Mandal and traditionally associated with the library upon whose steps Humayun fatally fell in 1556, less than a year after his successful return to India. Abu al-Fazl, the official chronicler of Humayun`s son and successor, Akbar, pens that the building in which Humayun had his fatal accident had only recently been completed, presumably by Humayun himself. The pavilion`s design, quite intimate to Timurid garden pavilions and unlike Delhi Sultanate architectural types, suggests an incredible Mughal patronage.

Khwand Amir, a noble in Humayun`s court, reports that by 1534 the "walls, bastions, ramparts and gates" of Humayun`s Din-Panah were almost wrapped up, adding that it was hoped that the "great and lofty buildings" of the city soon would be finished. It is yet again difficult to state from Khwand Amir`s verbose prose exactly how much of the city in reality was ready by 1534. Humayun`s dream of Mughal architectural beauties had only remained in his dreams due to his constant engagements with Sher Shah Suri and guaranteeing his central Delhi throne. Mughal architecture during a much wobbly Humayun states that, almost certainly he had built the fort`s small octagonal pavilion, acknowledged as the Sher Mandal and traditionally associated with the library upon whose steps Humayun fatally fell in 1556, less than a year after his successful return to India. Abu al-Fazl, the official chronicler of Humayun`s son and successor, Akbar, pens that the building in which Humayun had his fatal accident had only recently been completed, presumably by Humayun himself. The pavilion`s design, quite intimate to Timurid garden pavilions and unlike Delhi Sultanate architectural types, suggests an incredible Mughal patronage.

The sole inscribed monument belonging to Humayun`s patronage is a mosque in Agra, known after the name of its locality, Kachpura. Two inscriptions also gladly indicate that the mosque was completed in 1530, the year of Humayun`s accession to the throne. It is evident from such pieces of information that Mughal architecture during Humayun was a one of transition - moved away from maturity and uncomplicatedness of Babur, yet not much lofty and meticulous like Akbar.

On the mosque, eight-pointed stars and lozenge patterns are embossed into the rectangular facade; possibly these were once painted to accentuate the design, conjuring up the brilliantly coloured glazed tile ornamentation of Herat and Samarqand. The mosque is however in ruins in contemporary times, so it is highly unclear how many bays originally composed the double-aisled side wings. While no traces of enclosure walls and entrance gates remain, they were almost undoubtedly part of the original plan. The overall appearance and plan of this structure suggests that it, just like Babur`s Panipat mosque, was designated to emulate older Timurid types. It is thus very much a testified endeavour that Humayun, like his father Babur, could not also just make himself separated from Timurid influences, their tremendous ancestral Timur and his sway was still much visible in architectures in India, as late as standing in a difference of more than 200 years!

As such, Mughal architecture during Humayun was also very much not alienated from Babur`s, however, attempts all did go down the drain, due to his overindulgence in pleasurable pursuits and too unmindful ness to his realm and consequential architectural excellences.