About Malayalam Theatre

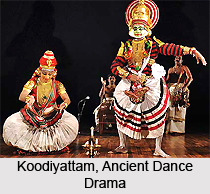

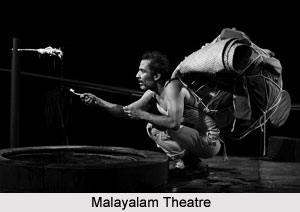

History of Malayalam theatre speaks at great length about the various phases of theatre culture in the state. The history of theatre culture in the Indian state of Kerala can be distinctly divided into two main types; Medieval Malayalam Theatre and Modern Malayalam Theatre, respectively! The history of Malayalam theatre is ancient in origin. This is known even though the dramatic Malayalam literature i.e. the language spoken in southern state of Kerala is of somewhat recent origin. Its oldest extant genre, Kutiyattam, fully established by the ninth century, may well represent the longest-surviving continuous theatrical tradition in the world. It is a system of staging classical plays in Sanskrit language, but not entirely Sanskrit theatre in the strict sense because the enactment contains elaborate oral elucidation in Malayalam language. Still, it was Kerala first performing art based on written texts, and evidently served as a basic model of creative expression for all later forms in Malayalam.

History of Malayalam theatre speaks at great length about the various phases of theatre culture in the state. The history of theatre culture in the Indian state of Kerala can be distinctly divided into two main types; Medieval Malayalam Theatre and Modern Malayalam Theatre, respectively! The history of Malayalam theatre is ancient in origin. This is known even though the dramatic Malayalam literature i.e. the language spoken in southern state of Kerala is of somewhat recent origin. Its oldest extant genre, Kutiyattam, fully established by the ninth century, may well represent the longest-surviving continuous theatrical tradition in the world. It is a system of staging classical plays in Sanskrit language, but not entirely Sanskrit theatre in the strict sense because the enactment contains elaborate oral elucidation in Malayalam language. Still, it was Kerala first performing art based on written texts, and evidently served as a basic model of creative expression for all later forms in Malayalam.

The methodological infrastructure employed in the study of Malayalam theatre, in the broadest sense, incorporates the historical-materialist theoretical framework. The equality and democratic collectiveness of the pre-historic communities of Kerala had been completely destroyed by the newly emerged, undemocratic social apparatus based on `high` and `low` castes. Social life in Kerala was in no way fundamentally different from the rest of India. Kerala`s caste organization was, if anything, even more unequal than in other parts of India; the system of untouchables here was far more rigorous.

It is true that most of the cultural and art forms arose within the narrow compass of one caste or group of castes belonging to separate class categories. The classical literary works of Malayalam were mostly produced by Hindu authors and dealt with Hindu religious themes; so were Kathakali, Koodiyattom and other arts mainly of Hindu origin. It is also true that most of these national literary and art places were confined to upper caste (class) circles. Nevertheless, these works of literature and art forms have laid the basis for the creation of a style and technique that go beyond all castes and communities; they are truly national. Moreover, men of culture, drawn, of course, from the upper classes but of all castes began to appreciate and even adopt this style and technique in their own particular caste or religious circles. The Chavittunatakam of the Christians is a simplified adaptation of the Kathakali form of the Hindu.

History of Malayalam theatre, in the ultimate analysis, is the history of performance and performance of any kind is a socio-cultural act. Basing oneself on the assumption that all cultural artefacts are socially symbolic acts, one has to realize that in order to articulate the past historically, it is not sufficient to recognize it "the way it was".

One aspect in which this wide and varied culture has found expression is the stage and performance which had made its valuable contribution to the sum total of Indian culture. The orthodox section of this stage which has a religious atmosphere attached to it and is, therefore, beyond the gaze of profane eyes, plays no inconsiderable role in helping the reconstruction of the ancient Sanskrit stage - the active traditions of which have died out elsewhere in India.

Malayalam as a distinct language had its formulation almost a thousand years back and Malayalam drama in the form of the texts written by the Sanskrit dramatists and European dramatists has only a history of hundred years. Indian theatre or Sanskrit theatre has a tradition, as every one knows, which goes back thousands of years. Kerala which had been closely linked with the Brahmanical tradition for centuries had to wait till 1898 to find the first dramatic text to be produced, that too a translation of Kalidasa`s Sakuntalam. This does not mean that Keralites had no theatre movement of their own. On the other hand, the tradition of Sanskrit drama find itself manifested only in Kerala in the form of Koodiyattom and lot of Sanskrit plays derived from Sanskrit Literature have been written by Keralites in the past. But, there was not even a single drama in Malayalam till 1898 when all other areas of literature were making headway.

The simple reason usually attributed is that of the dominance of ideologies related to Sanskrit and Brahmans, over the vernacular. It may be true that Brahmanical dominance might have discouraged every development based on the vernacular culture. But the change in the sensibility which came to manifest itself in the people for the emerging language made the dominant ideological machinery of the upper castes disturbingly silent. The result was that the complex technicalities and structure of the feudal arts forms gave way to much more simpler theatrical experience for the people. But these innovations could not provide any lasting contribution towards the development of modern Malayalam theatre. The origin of modern Malayalam theatre which took place in the second half of nineteenth century finds itself distanced by atleast hundred years from the Christian theatrical forms.

It was indeed a major event in the performance history of Kerala that a Sanskrit play got translated into Malayalam, (the hybrid variety of Malayalam which is known as manipravalam) for the first time by a person belonging to the feudal class structure. The ideological underpinnings of the innumerable translations of plays from Sanskrit and English created an atmosphere which was very much in accordance with the value systems of ruling class. It must also be remembered that almost all the translations were not performance-oriented and the reason for this can also be attributed to the dominance of theatrical forms like kathakali which could fulfil the theatrical urges of the upper classes in general.

A major change in the style of producing a dramatic text with a newly structured performance pattern which is known as Sangeetha Natakam (musical drama) is worth mentioning in this context. In the history of modern Malayalam performance patterns, this new development which had spread over to Kerala from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka demands particular attention from a socio-political perspective. The verse form of this performance pattern which developed slowly was very much based on the vernacular Malayalam with its highly flexible metrical pattern and this was really a major break through in the performance history of Kerala.

In 1889, Chathukutty Mannadiar translated Ramabadradikshita`s Janaki Parinayam and Bhavabhuti`s Uttara rama charitam, which stood even above the translation of Kerala Varma`s Sakuntalam. The language employed by Mannadiar was highly relaxing and acceptable to the majority than the intellectualised Sanskrit/Malayalam of Kerala Varma.

Some original plays were based on themes from epics and stories from history. Thottakkad Ikkavamma`s Subhadrarjunam, Natuvattachan Namboodiri`s Bhagavadoodu, Kunhikkuttan Tampuran`s Lakshmana sangam, Varghese Mapila`s Ebrayakutty based on the Old Testament are all worth mentioning in this context. K.C. Keshava Pillai`s Sadarama and T.C. Achutha Menon`s Sangeethanyshadham; Kuttamath Kanniyoor Krishna Kurup`s Balagopalan were the most popular sangeethanatakams of Kerala.

The effervescence in this form of theatre activity was inspired by the famous actor Thiruvattar Narayana Pillai who organized the first professional theatre company manomohanam in the south of Kerala. In central Kerala Chathukutty Mannadiar gave shape to rasikaranjini natana sabha. But in the north of Kerala this musical drama movement had a different orientation other than purely being commercial. Vidwan P. Kelu Nair`s (Pakkanar Charitam, Lanka Dahanam, Paduka Pattabhishekam, Srikrishna leela, Kabeerdasa Charitam, Vivekodayam) plays and their presentations were very popular especially in Malabar in the 20`s. The Sangeetha Nataka performance pattern in Malabar popularised by Vidwan P. Kelu Nair, Kuttamath Kunniyur Kunhikrishna Kurup(Harischandracharitam, Devayanee-charitam etc.) Ananthan Nair (Kuchelagopalam), Kunhambu Kurup (Vydarbhivasudevem, Amsumathidha ramagupta etc.) and a host of others in collaboration with great actors like Rasikashiromani P. Koman Nair, C.U.K. Nambiar, Malabar Raman Nair stands apart mainly in one respect from the tradition. One can obviously find certain elements like the affinity for themes from epics and the dominance of carnatic music in the Sangeetha Nataka tradition of Kerala. But in Malabar this performance pattern had its roots in the turbulent struggles for national liberation and most of the playwrights of this form were involved in one way or another in the national liberation struggle. Most of them had the experience of being in prison for participating in the struggles of the period. The newly emerged theatre practice, they thought, would inspire the people to make their contributions towards the transformation of Kerala society in particular and Indian society in general.

The effervescence in this form of theatre activity was inspired by the famous actor Thiruvattar Narayana Pillai who organized the first professional theatre company manomohanam in the south of Kerala. In central Kerala Chathukutty Mannadiar gave shape to rasikaranjini natana sabha. But in the north of Kerala this musical drama movement had a different orientation other than purely being commercial. Vidwan P. Kelu Nair`s (Pakkanar Charitam, Lanka Dahanam, Paduka Pattabhishekam, Srikrishna leela, Kabeerdasa Charitam, Vivekodayam) plays and their presentations were very popular especially in Malabar in the 20`s. The Sangeetha Nataka performance pattern in Malabar popularised by Vidwan P. Kelu Nair, Kuttamath Kunniyur Kunhikrishna Kurup(Harischandracharitam, Devayanee-charitam etc.) Ananthan Nair (Kuchelagopalam), Kunhambu Kurup (Vydarbhivasudevem, Amsumathidha ramagupta etc.) and a host of others in collaboration with great actors like Rasikashiromani P. Koman Nair, C.U.K. Nambiar, Malabar Raman Nair stands apart mainly in one respect from the tradition. One can obviously find certain elements like the affinity for themes from epics and the dominance of carnatic music in the Sangeetha Nataka tradition of Kerala. But in Malabar this performance pattern had its roots in the turbulent struggles for national liberation and most of the playwrights of this form were involved in one way or another in the national liberation struggle. Most of them had the experience of being in prison for participating in the struggles of the period. The newly emerged theatre practice, they thought, would inspire the people to make their contributions towards the transformation of Kerala society in particular and Indian society in general.

The play Chakkichangaram by Munshi Rama Kurup made a fierce attack against this onslaught of the new type of performance pattern. It is against the vulgarisation of taste that Rama Kurup took arms against. The play was in the form of an English farce and it had the aim of cleaning the taste and sensibility of the upper middle class which was being polluted by the sub-culture of the Tamil musical drama and the imitations in Malayalam based on them which were becoming very popular.

Moreover, cultural practice in the vernacular was looked at with contempt; by those belonging to the upper strata but the social forces that unchained the human energy in this particular period was beyond the control of the ruling class alliance of the British and the regional monarchies. It is to be noted that even as early as 1880`s when the commercial theatre practice based on Sangeetha Nataka tradition was making its headway in the south of Kerala, in the north Malabar and Malabar in general this tradition was being nurtured with a radical perspective. This radical development in performance practice, it can be rationally argued, did exert great influence upon the progressive theatre movement of Kerala in general which started with V.T. Bhattathiripad in 1929.

Development of Malayalam Theatre

Development of Malayalam theatre can be categorically divided into various phases. The history of Malayalam theatre weaves together all the possible features of development in the state. The first social play in Malayalam may be said to be Mariamma (1903) by Kocheeppan Tharakan. Then there was the beginning of Tamil Theatre - tradition which owes its origin to the revival of Carnatic Music, by the then King of Travancore, Swathy Thirunal. During this time the decorative elements of Parsi Theatre also had been fairly pronounced on the Malayalam Theatre. Struck by the feeling that this imitative trend was inferior to the native culture, some outstanding playwrights of the time wrote some notable plays of the early period. Some of the important plays are Sangeethanaishatham by T.C. Achuthamenon, Sadarma by K.C. Kesava Pillai, Pakkanarcharitham by Vidwan Kelunayar. It was at this time that the Chavuttunatakam and Kalaripayattu elements found their way into the Malayalam theatre.

Development of Malayalam theatre can be categorically divided into various phases. The history of Malayalam theatre weaves together all the possible features of development in the state. The first social play in Malayalam may be said to be Mariamma (1903) by Kocheeppan Tharakan. Then there was the beginning of Tamil Theatre - tradition which owes its origin to the revival of Carnatic Music, by the then King of Travancore, Swathy Thirunal. During this time the decorative elements of Parsi Theatre also had been fairly pronounced on the Malayalam Theatre. Struck by the feeling that this imitative trend was inferior to the native culture, some outstanding playwrights of the time wrote some notable plays of the early period. Some of the important plays are Sangeethanaishatham by T.C. Achuthamenon, Sadarma by K.C. Kesava Pillai, Pakkanarcharitham by Vidwan Kelunayar. It was at this time that the Chavuttunatakam and Kalaripayattu elements found their way into the Malayalam theatre.

Some of the historians have claims that a successful theatre form came into existence only with the coming of the Portuguese. A study of the plays of this period does not reveal the theatrical functions of rituals being utilised. In Mariamma which is considered to be one of the first accomplished plays in Malayalam exorcist ritual was introduced with the aim of giving an insight in to the social vagaries of the time. But the theatre of the time did not expose any awareness of the ritual functions in their deeper levels of actor, audience or other elements.

The history of Malayalam Theatre from 1900 to 1930 shows the new flourishing of Sangeethanatakas with the influence of Sanskrit tradition that continued for sometime. But disgusted with this, playwrights like C.V. Raman Pillai and E.V.Krishna Pillai began to write farces. No ritual influence on the Malayalam theatre is perceived here. The period from 1930-40 clearly shows a Western influence especially through the translation of Shakespearean plays. Here also the importance of the theatrical functions of rituals was unknown to it. It was in this period that social reformative plays began to appear. Plays like Adukkalayil Ninnu Arangathekku (1930) by V.T.Bhattathiripad, Pattabakki (1937) by K. Damodharan, Rithumathi (1940) by M.P.Bhattathirippadu belong to this period.

The period from 1940 to 1950 in Malayalam Theatre shows a revival. The emergence of a new phase in Malayalam Theatre with a direct influence of the Western tradition came in to existence. It was then that N. Krishna Pillai with his visible influence of Ibsen began to write plays, centred on the psychological problems of man and society, like Kanyaka (1944) Bhagnabhavanam (19491, Balabalam (1946) etc. The entrances and exists of this character, his choric function in the theatre, revives ritual memories. They provide the whole play with a metaphysical atmosphere.

The period of Malayalam Theatre from 1950-60 is very rich in its output. The stress on the socio political aspect by the theatre is the particular trend in this period. The emergence of Thoppil Bhasi with the famous theatre troupe of K.P.A.C. is the most important event of this period. But the uses and functions of rituals as a theatre device was not seen here. It was in this period some notable dramatists like P.J. Antony, S.L. Puram Sadanandan, N.N. Pillai, K.T. Muhammed etc. made their debut in Malayalam Theatre. But no awareness of indigenous culture is traceable in their Theatres.

Consequently, a few dramatists like C.N. Sreekantan Nair, G. Sankara Pillai, Kavalam Narayana Panikkar etc. tried some innovate techniques in theatre. Thus the experimental phase of Malayalam Theatre began. It is seen in this period that a new approach to Malayalam Theatre was taken. It was also as a part of the revival of the indigenous tradition of the Country in all spheres including art and literature. There arose also the feeling that the Western form was not sufficient to give full dramatic expression of the indigenous themes. Theatre men like Mohan Rakesh of the Hindi Theatre, Vijay Tendulkar of Marathi Theatre, Girish Karnad of Kannada Theatre, C. N.Sreekantan Nair and G.Sankara Pillai of Malayalam Theatre aspired for an indigenous form. Thus they began to dream of a meaningful theatre with a new indigenous culture.

As Malayalam Theatre has a great theatre-tradition based on rituals arts, the ritual concepts of the actor and audience began to tell upon it. During this time theatre workshops by important theatre personalities like M.Govindan, G.Sankara Pillai, C.N. Sreekantan Nair, Kavalam Narayana Panikkaretc. Were conducted in different parts of Kerala, and this new aspect of theatre was discussed in detail. The result was the call for an indigenous theatre in Kerala which is being called Thanathu Nataka Vedi. Thus the theatre workers began to look to the rich traditions of the ritual arts of Kerala for developing a new trend in the Modern Malayalam Theatre, a new concept based on the actor-audience relationship.

Contemporary Malayalam Theatre

Contemporary Malayalam theatre has a rich heritage behind it, and has indeed come a long way from its past. Just like in any other part of India, Malayalam theatre has also seen a lot of growth in its field. Many theatre enthusiasts and critics felt that the theatre of Kerala did not yield the result as dreamed and expected. Some confusions and perplexity still remain among the people regarding the structure and from of the nature and the medium of production. Some critics are of the opinion that mad experimentation with the themes and plots of the plays have resulted in driving the audiences away.

Contemporary Malayalam theatre has a rich heritage behind it, and has indeed come a long way from its past. Just like in any other part of India, Malayalam theatre has also seen a lot of growth in its field. Many theatre enthusiasts and critics felt that the theatre of Kerala did not yield the result as dreamed and expected. Some confusions and perplexity still remain among the people regarding the structure and from of the nature and the medium of production. Some critics are of the opinion that mad experimentation with the themes and plots of the plays have resulted in driving the audiences away.

Presently, the practitioner of Kerala theatre is well aware of the aesthetics and crafts of his medium, as his contemporary at any other part of the cosmos. The lack of material and finance resources created another strange scenario for the theatre enthusiasts of Kerala. Initially, however, the government of the state was not too friendly into helping theatre culture to flourish in the state. The State Sangeetha Nataka Academy manages the schedule for organizing theatre in the state, but the lack of fund sometimes deter them from taking necessary steps. State Sangeetha Nataka Academy organizes theatre festival in the state which attracts huge crowds from across the country and around the world. The taker for Malayalam theatre in the contemporary scenario is dismal. The acceptance is slowly fading away. As a result it is seen that theatre enthusiast either to the film or TV or to other engagements, in his pursuit to earn a livelihood. Adding to the worry, people envisage disillusionment and confusion in the future of Malayalam theatre. The major complain, however, has been that the present theater is not addressing to the social and human issues as it did in the past.

Having said all that, one must always remember that the Malayalam theatre has evolved amidst dilemmas and confusions. The last fifty years of theatre in Kerala has been very productive as it has seen a lot of constructive changes, both in content and concept, in form and organization. Going by the history of Malayalam theatre, the major development or growth of this theatre occurred in the first twenty-five years of this century. Then this from of art was used in addressing social issues. With time, new improved technologies were brought in to develop Malayalam theatre. A lot of successful drama were staged and a good number of these sensible productions, contributed to the formation of the present Keralite identity with a rational and a reasonable social outlook.

After the independence of India the story of Kerala theatre changed drastically. The thumping success of socially progressive plays like Ningalenne Communistakki and the productions of Malabar Kendra Kalasamithi inspired a mainstream theatre culture that gradually fell into the rut of repeated cliches and formulas in content, structure, acting, music and all departments of the production. During this time, young playwrights with potential like; C.N.Sreekantan Nair and C.J.Thomas have written plays that did not confirm to the run of the mill creations of the period. Still their plays like Lankalakshmi and Aa manushyan nee thanne (That man is you) did not resulted in productions until 1975. After the British left India, country was familiarizing itself with the growing awareness of theatre culture. New institutes and schools began were set up in order to impart theatre education to the people. Though, the first theatre school was set up at Trichur in the year 1978, education of theatre was introduced much before through theater workshops - Nataka Kalaries, organized by late G.Sankara Pillai and others. Malayalam theatre started to develop as an art from with its own aesthetic standards and one that demanded stern and continuous assurance from the artists. The urge to evolve theatre practice, rooted in Indian performance tradition, was joined by Kavalam Narayana Panikker, G Sankara Pillai, R.Narendra Prasad and others with productions like Avanavan Kadamba (the self-fence), Karimkutty (both by Kavalam Narayana Panikker), Karutha daivathe thedi (In search of the black god) by G.Sankara Pillai, and Souparnnika By R.Narendraprasad, and also with the theoretical comprehension.

During the late seventies and early eighties saw a quantum jump in the concept and practice of Malayalam theatre. Many young theatre enthusiasts made their own troupes and theatre companies. This actually helped promoting the Kerala theatre culture. The street plays put up by Kerala Sastra Sahithya Parishat had good theatre in it. The productions like Nattugaddika (by K.J.Baby) - performed by the tribal of the Vayanadu district along with the activists of Communist Party of India Liberation, with a content that is highly political, theme and structure evolved from the tribal myths and rituals, presented in a sort of street corner, during the period of emergency under strong police vigil and threats of arrest - gave new meanings to the purpose and practice of theatre.

During the late seventies and early eighties saw a quantum jump in the concept and practice of Malayalam theatre. Many young theatre enthusiasts made their own troupes and theatre companies. This actually helped promoting the Kerala theatre culture. The street plays put up by Kerala Sastra Sahithya Parishat had good theatre in it. The productions like Nattugaddika (by K.J.Baby) - performed by the tribal of the Vayanadu district along with the activists of Communist Party of India Liberation, with a content that is highly political, theme and structure evolved from the tribal myths and rituals, presented in a sort of street corner, during the period of emergency under strong police vigil and threats of arrest - gave new meanings to the purpose and practice of theatre.

Almost all villages in the Indian state of Kerala organized theatre competitions that have also been the school for many theatre workers to breed. Popular theater personalities came to the fore, who made tremendous impact later on. However, this boom did not last for a long time as desperation and confusion creped in. With too much experimentation, the quality of the contents was seriously sacrificed and as a result the audience slowly turned away. Many of the potential talents left theatre for films as actors or technicians.

During such a dire strait, foreign investment somewhat helped Malayalam theatre to look up as talented directors and artists were wooed into their trap and very talented and promising directors like Jose Chiramel were the first among the prey. Presently the Kerala Theater is still in the phase of reemerging. All the concerned groups are working towards bring back the golden phase of the Kerala theatre.

Groups like Lokadharmi Thrippunithura, Abhinaya Thiruvananthapuram, and Center for performing arts Kollam, Jananayana Vadanappalli, A.S.Smaraka Kalavedi Karalmanna, Desaposhini Kozhikodu, and Annoor peoples arts club Payyannoor are doing effective work with a clear vision against all odds and have come with meaningful productions.

Modern Malayalam Theatre

Modern Malayalam theatre encompasses some of the interesting phase of theatre culture in the state. By 1900 one could visualize a gradual shift in the structure of sensibility of the people of Kerala, especially the educated middle class and the progressive minority.

Modern Malayalam theatre encompasses some of the interesting phase of theatre culture in the state. By 1900 one could visualize a gradual shift in the structure of sensibility of the people of Kerala, especially the educated middle class and the progressive minority.

The "Malayali Memorial" struggle also radically changed the whole sensibility of the middle class intellectuals of south Kerala and elsewhere. Intellectuals like G.P. Pillai, C.V. Raman Pillai, Swadeshabhimani Ramakrishna Pillai, C. Krishna Pillai and Kumaran Asan in particular started expressing themselves in a different tone and idiom and the people felt themselves being drawn to an alternative ideological domain which was basically antagonistic towards the hegemonic ideology of Brahmanism and British rulers.

The theatrical performance strategies developed during this period is to be examined in the light of the newly emerging social consciousness among the educated and the uneducated. In 1909 Kumaran Asan`s Veena Poovu (The Fallen Flower) was a radical break through in the field of Malayalam poetry. Though the force of C.V. Raman Pilla`s Kurupilla Kalari (1909) did not in any way open the doors of a new age in the history of Malayalam theatre, it can be considered as a piece which created a change in the form and content of modern Malayalam dramatic representation. C.V. Raman Pillai pushed out the abundance of music and the conventional "Raja Part" (role of King) from his plays. But the ideological influence of Kochunni Tampuram (Kalyani Natakam) K.C. Keshava Pillai (Lakshmi Kalyanam) and Munshi Rama Kurup (Chakki Changaram) can be felt in the plays of C.V. and the major playwrights of the period E.V. Krishna Pillai, N.G. Keshava Pillai, N.P. Chellappan Nair and T.N. Gopinathan Nair.

The year 1929 is most significant in the sense that V.T. Bhattathiripad wrote his play Adukkalayil Ninnu Arangathekku. It was the first play in Malayalam to have a definite and concrete social objective and which was produced in 1929 itself as part of a very powerful social reformist movement led by Namboodiri Yogakshema Sabha. The degenerate Brahmanical ideology and its social structure had its first powerful assault from within for the first time and the most fervent slogan of the period was for the transformation of "Brahmans into human beings".

From the 1930`s to 1940`s Malayalam performance patterns changed so radically that the structure of human experience encapsulated in them underwent thorough transformation from that of the Sangeetha Nataka style. The result was the emergence of political theatre in Malayalam in the real sense of the term. This new performance pattern which was basically realistic reached every nook and corner of Kerala to establish a lasting effect upon the future developments in the radical theatre practice of Kerala. It is indeed illuminating to have a glimpse at the overall social background of the origin of radical political theatre movement in Kerala. Malayalam theatre practice came of age in 1937 and the subsequent developments in Kerala theatre very clearly indicates the class-contradictions embedded at the core of the fast changing social formations.

The historic struggles which shook the foundations of the British Empire in India during the period 1940 to 1947 had their far-reaching implications in art and culture of Kerala. As early as in 1936 when the political arena in Kerala was becoming more and more tense with the peasant landlord antagonism and anti-British movement, the ideological intellectualism of the middle class was struggling to find strategies of containment in various fields of creative activity.

There were highly talented actors like P.K. Vikraman Nair, who were also dead against the superficial farces being presented and "enjoyed" by the people. Krishna Pillai`s plays were produced with the backbone given by the prominent actors of Tiruvananthapuram. The themes of N. Krishna Pillai`s plays do not bear any testimony to the gathering storm. The main burden of the plays of the forties-man-woman relation-reflects the newly acquired consciousness of playwrights like N. Krishna Pillai.

The theatre history of the 1940`s will not be complete if the intervention of two playwrights, Pulimana Parameswaran Pillai and C.J. Thomas, can be excluded, who were adventurous enough to go beyond the realms of Ibsenist fixation of the period. Pulimana`s Samathwavadi (1944) was a courageous experimentation in theatre practice which can be categorised as the first expressionist play in Malayalam which for many reasons got recognised and produced only in the sixties.

C.J. Thomas, whose play written in the forties, Avan Veendum Varunnu (1949), thematically listens to the Second World War and tries to sort out one of the crises which disturbed the social life of Kerala-Absentee-husbandism. From 1942 to 1947 is a period of intense political activity resulting in Indian Independence. With the transfer of power and establishment of Government of India at the centre and states, things changed rapidly. The inhuman massacre of minorities and the subsequent exchange of population cast a shadow too deep for any other thought and it was in the fifties that the country started settling down.

But, by 1949, seeds were sown for the future furthering and development of radical theatre practice by progressive play-wrights like Edasseri Govindan Nair (Kootukrishi-1949). The presentation of this play heralded a revitalised and organised theatre culture especially in Malabar.

The organized theatre movement in Malabar under the banner of Malabar Kendra Kalasamithi can be looked upon as the logical continuity of the political theatre movement in Kerala inaugurated by K. Damodaran`s Pattabakki. Apart from these bright patches the stage in the forties in Kerala was dominated by trivial farces and melodramatic presentations overburdened with music and sentimental songs.

But the fifties in Malayalam theatre presents a very different picture and the dominance of the theatre culture of the Indian People`s Theatre Association (IPTA) had given impetus to a radical collectivity which shaped innumerable amateur theatre groups in Kerala, mostly under the guidance of the Communist party. The most significant aspect of the impact of IPTA, it can be argued, is that for the first time in Kerala, the Communist party formulated a cultural policy and programmes of its own. What came as a result was another theatre organisation similar to that of Malabar Kendra Kala Samithi: K.P.A.C. (Kerala People`s Arts Club) which spearheaded a powerful people`s theatre movement in Kerala. The agitprop nature of the most prominent of the plays produced by K.P.A.C., Ningalenne Communistakki, was part and parcel of the Communist movement in Kerala and the performance design of the play had immediate impact upon the audience.

The period from 1950 to 1957 has to be examined in the light of the powerful progressive theatre movement developed by Malabar Kendra Kala Samithi. This theatre movement of the left with definite ideological affinities with the IPTA and having its dynamic nucleus in Kozhikode conducted theatre festivals which influenced the future developments in radical theatre practice in Kerala. In a way, it was the beginning of a cultural renaissance in Malabar under the leadership of Malabar Kendra Kala Samithi, which did not concentrate on theatre practice alone but on all other cultural fronts. It was the era in which the people`s library movement - Kerala Grantha Sala Sangham - formulated its programmes which were basically an attempt to raise the consciousness of the people in the villages and almost all the libraries and reading rooms thus conceived had a theatre organization, attached to them. This cultural action for freedom, in the broadest sense, unleashed the hidden potential of the village communities in Malabar. The idea of village theatre gatherings gained.

The period from 1950 to 1957 has to be examined in the light of the powerful progressive theatre movement developed by Malabar Kendra Kala Samithi. This theatre movement of the left with definite ideological affinities with the IPTA and having its dynamic nucleus in Kozhikode conducted theatre festivals which influenced the future developments in radical theatre practice in Kerala. In a way, it was the beginning of a cultural renaissance in Malabar under the leadership of Malabar Kendra Kala Samithi, which did not concentrate on theatre practice alone but on all other cultural fronts. It was the era in which the people`s library movement - Kerala Grantha Sala Sangham - formulated its programmes which were basically an attempt to raise the consciousness of the people in the villages and almost all the libraries and reading rooms thus conceived had a theatre organization, attached to them. This cultural action for freedom, in the broadest sense, unleashed the hidden potential of the village communities in Malabar. The idea of village theatre gatherings gained.

Jeevitham, Prasavikkatha Amma, Nirahara Samaram, Pazhaya Bandham, Kanyadanam (all by Thikkodiyan), Mannum Pennum, Thee Kondu Kalikkaruthu (P.C. Kuttikrishnan- Uroob), Tharavatitham, Sneha Bhandhangal, Manushya Hridayangal, Janma Bhoomi, (all by Cherukad); Karavatta Pasu, Ithu Boomiyanu, Velichum Vilakkannveshikkunnu, Manushyan Karagrihathilanu Puthiya Veedu, Rathri Vandikal , Njan Petikkunnu, Chuvanna Gatikaram (all by K.T. Mohammed); Kandam Vecha Kottu (Mohammed Yoosuf); Tharavadum Madissilayum (P.N.M. Alikkoya); Prabhatham Chuvanna Theruvil (A.K. Puthiyangadi) and so many other plays were either meant for presentation during the great theatre festivals or for presenting before village communities.

In the south of Kerala as well, the fifties have given rise to certain progressive trends in theatre culture. The amateur theatre practice was mainly centred upon the plays of T.N. Gopinathan Nair. Another attempt, which did not last for long was the formation of Navasamskara Samithi which reviewed the presentation of play like Avan Veendum Varunnu (C.J. Thomas), what matters most in this context is the active participation of eminent theatre personalities like K.V. Neelankandan Nair, P.K. Veeraraghavan Nair and P.K. Vikraman Nair to accelerate the process of creating a theatre atmosphere which could basically challenge and change the trivial theatrical practices of the times. But the impact of their efforts did not last long even though the stage in Tiruvananthapuram did produce serious presentations like Thoovalum Thoombayum (P.K. Veeraraghavan Nair), Nashtakkatchavadam (C.N. Sreekantan Nair) Kunhali Marakkar (K. Padmanabhan Nair). Commercial theatre practice had a tremendous appeal among the masses especially in the south in the fifties for one reason or other.

The only serious venture in the midst of innumerable populist commercial theatre practice was the work of C.N. Sreekantan Nair. He in fact had tried to formulate his own performance theory which inspired serious individualist dramatists and theatre activists like G. Sankara Pillai and Kavalam Narayana Panickar to experiment and codify their theatre practices in meaningful ways.

The decline of the radical progressive theatre practice after the infamous "liberation struggle" of 1959 gave added energy and enthusiasm to those theatre activists who were deliberately maintaining strategies of silence when social life in Kerala was being shaken by the forces of degenerate communal and ruling class political ideologies.