Introduction

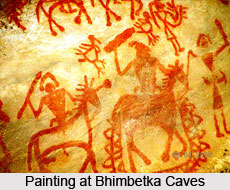

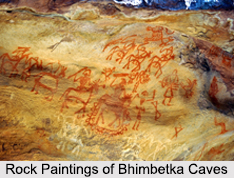

History of Indian paintings has lots of riches for people to enjoy and experience. For the usual humid climate in India the preservation of paintings have been difficult than other forms of art. Some of the earliest Indian paintings have been rock paintings of the prehistoric times. In places like Bhimbetka, petrogyyphs are found, some of them happen to be from 5500 BC.

History of Indian paintings has lots of riches for people to enjoy and experience. For the usual humid climate in India the preservation of paintings have been difficult than other forms of art. Some of the earliest Indian paintings have been rock paintings of the prehistoric times. In places like Bhimbetka, petrogyyphs are found, some of them happen to be from 5500 BC.

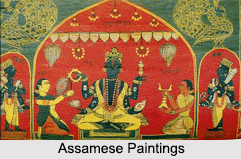

Buddhist Literature in India is filled with examples of texts which go on to describe mansions of kings and aristocratic class overstated with paintings, but the Ajanta Caves are very significant of them all. Indian paintings offer a visual variety which expands from the early evolution to the present day. From being basically religious in purpose in the beginning, Indian painting has developed over the years to become a combination of a variety of cultures and traditions.

Six Limbs of Indian Painting

Around the early period of 1st century BC there evolved Six Limbs of Indian Paintings or Sadaga. These `Six Limbs` have been translated as follows:

Rupabheda: The knowledge of appearances.

Pramanam: Correct perception, measure and structure.

Bhava: Action of feelings on forms.

Lavanya: Yojanam Infusion of grace, artistic representation.

Sadrisyam: Similitude.

Varnikabhanga: Artistic manner of using the brush and colours.

Ancient Indian Painting

Ancient Indian art has seen the rise of the Bengal School of art in 1930s pursued by a lot of forms of experimentations in European and Indian styles. With the development of the economy the forms and styles of art also undergo many changes. Monuments of the exceptional value are Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, here, more than 500smaller rocks and caves contains thousands of paintings. Some of the oldest paintings here are more than 15000 years old, and in some cases it is 30,000 years old. The prehistoric art from is spread all over India from snow covered Himalayas to south of Tamil Nadu.

Indian Cave Paintings are regarded as the earliest evidences of Indian paintings which are made on cave walls and palaces while miniature paintings are small-sized colourful, intricate handmade illumination. This starts from prehistoric cave painting of Bhimbetka and flourishes through cave paintings of Ajanta caves, Ellora caves and Bagh.

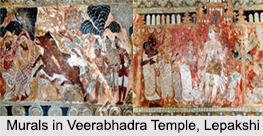

History of Indian Cave Paintings like that of Ajanta and Ellora refers to the Buddhist monks who employed painters to draw the life and teachings of Lord Buddha and Buddha Jataka on the walls of the Ajanta caves, where they painted the figures along with their costumes and jewelleries in beautiful colours and style while in Ellora caves the paintings are mostly of Hindu deities.

History of Indian Cave Paintings like that of Ajanta and Ellora refers to the Buddhist monks who employed painters to draw the life and teachings of Lord Buddha and Buddha Jataka on the walls of the Ajanta caves, where they painted the figures along with their costumes and jewelleries in beautiful colours and style while in Ellora caves the paintings are mostly of Hindu deities.

Medieval Indian Paintings

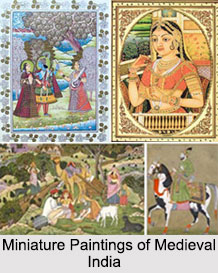

During Medieval period, India observed important development in the field of art of painting. The Medieval India is the part of Indian history between the 8th century and the 18the century A.D. The Persian tradition of miniature painting was also first introduced by the local rulers. It was during Akbar`s supremacy that the painting was organized by a grand concern which brought jointly Hindu and Muslim painters and artiÂsans from diverse parts of India, particularly, from regions like Gujarat and Malwa where manuscripts and miniature paintings had developed.

Mughal Paintings mainly describes Indo-Islamic design of painting and flourished in the ateliers of Mughal emperors including Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Tanjore Paintings are classical South Indian form of painting which evolved in the village of Thanjavur.

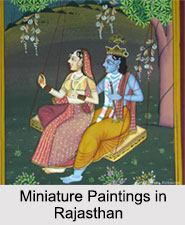

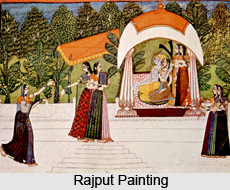

Rajasthani paintings are miniature paintings of the finest quality, which are made both on paper and on large pieces of cloth. A number of famous schools of painting are Mewar, Hadoti, Marwar, Kishangarh, Alwar and Dhundhar. It is also known as Rajput Paintings and has clear influence of Mughal paintings though it quite unique in its own way. Pahari Painting is the miniature painting evolved in the hilly states of Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir during the period of Rajputs. These paintings have beautiful scenes of Himalaya as the backdrop.

Rajasthani paintings are miniature paintings of the finest quality, which are made both on paper and on large pieces of cloth. A number of famous schools of painting are Mewar, Hadoti, Marwar, Kishangarh, Alwar and Dhundhar. It is also known as Rajput Paintings and has clear influence of Mughal paintings though it quite unique in its own way. Pahari Painting is the miniature painting evolved in the hilly states of Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir during the period of Rajputs. These paintings have beautiful scenes of Himalaya as the backdrop.

Indian Paintings in Pre-Historic Age

Indian paintings in pre-historic age dated back to the period which was found before the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation which was flourished during 3000 BC. Numerous portions of India bear the testimony of the changing forms of paintings which were flourished even during the primitive age.

Indian paintings in pre-historic age dated back to the period which was found before the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation which was flourished during 3000 BC. Numerous portions of India bear the testimony of the changing forms of paintings which were flourished even during the primitive age.

Historical records assert that the rock paintings or `petroglyphs` present in the rock shelters of Bhimbetka Caves in Madhya Pradesh are the earliest paintings in the country. Rock paintings have developed over the years and have given birth to more refined paintings, such as those in the Ajanta and Ellora Caves. Traces of rock paintings have been found on the walls of caves located in some districts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Bihar, and Uttarakhand.

Features of Indian Paintings in Pre-Historic Age

The initial forms of prehistoric art are exceptionally ancient. The cupules are a mysterious kind of Paleolithic artistic marking. The early sculptures recognized as Venuses of Tan-Tan and Berekhat Ram are simple illustrations of human shapes. It is not the Upper Paleolithic, which anatomically is contemporary man creates identifiable carvings and pictures.

Different types of Indian Paintings in Pre-Historic Age

Following are the different types of Indian Paintings in Pre-Historic Age:

Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka Caves: It is believed as an evidence of long cultural connection. It was discovered in 1957-58. It consists of almost 400 painted rock shelters in five clusters. The pre-historic paintings of Bhimbetka Caves are believed to be created with the aid of wooden sticks, feathers, needles of porcupines and other objects. Several paintings were done over previous paintings, which were not erased quite often. The themes of these paintings were mainly animals, birds and those inspired by the daily lives of primitive men. Symbols of a long feather denote a peacock; a trunk implies an elephant and decorative signs mean a female deer. Some paintings have been performed by a single stroke and others have been done in bright shades. Shapes like circles, triangles, hexagons and rectangles have been employed largely. Images of bows, arrows, weapons like knives and those of the struggles and accomplishments were depicted in the Bhimbetka Cave paintings. Pictures of violent battles have also been painted here. Many other pictures also demonstrate the images of group dances stick dances and mask dances.

Rock Paintings of Rajasthan: In the year 2010, an Indian archaeologist had discovered about 35 kms of paintings belonging to the pre-historic period in Garadha region of Bundi district in the state of Rajasthan. Images of tigers, antelopes, panthers and human beings were noticed in these paintings. These paintings are present in about 32 sites along with the basin of the River Mangli. Colours used are yellow, red, black and white. The painting which was discovered near Mirzapur in 1883 is considered to be the first primitive Indian painting. It portrays a rhinoceros which is attacked by six men, some of whom are dressed in headgears made of feathers. Ever since this time, several other primitive cave paintings have been found near Hosangabad, Bhimbetka, Singanpur, Pachmarhi and Raichur.

Miniature Paintings in Medieval India

The miniature paintings in medieval India ushered in by the rise of Islam to political supremacy in India and can be divided into two broad movements. One of these exemplifies an attempt to preserve past traditions with almost superstitious persistence. These traditions, though often emptied of meaning, retained at least the trappings of outer form which, in more propitious times, were again to quicken with life.

The miniature paintings in medieval India ushered in by the rise of Islam to political supremacy in India and can be divided into two broad movements. One of these exemplifies an attempt to preserve past traditions with almost superstitious persistence. These traditions, though often emptied of meaning, retained at least the trappings of outer form which, in more propitious times, were again to quicken with life.

The old and the new, the "foreign" and the "indigenous", had gradually come to terms with each other; and this process, in which the individual qualities of each were enhanced and brought to a new fulfilment, resulted in some of medieval Indian miniature painting"s greatest achievements. A mode of development in which fresh stimulus is received, reinterpreted, and transformed is hardly new to Indian art and can be seen at almost every great epoch in its history.

Origin of Miniature Paintings in Medieval India

The beginning of Indian miniature paintings can be traced back to the 6th and 7th centuries. Though, it was throughout the medieval period that this beautiful form of art flourished under the aid of the monarchs and aristocracy. In the western valleys of the great Himalayas Miniature School of Painting flourished in the form of both illuminations and independent pieces of art in the 17th century. The Indian miniature paintings were included in medieval manuscripts. The artists who created Indian miniatures, used a variety of materials to give their paintings an exceptional and eye-catching look.

History of Miniature Paintings in Medieval India

The history of Indian miniature painting from the 13th to the 19th century is filled with many riches and the information found supply only from the faintest indications of its wealth. The Mughal School had been studied for the longest time, so that it is more or less well known. As far as Rajasthani painting is concerned, most of the material has come to light only during the last twenty years or so. The broad currents are becoming clear but the details remain obscure, and fresh discoveries make constant reappraisal necessary. Many difficulties remain in the understanding of the Pahari style, though its obvious beauty and charm evoke an immediate response. This is applied to the various schools of the Deccan. Lacking the monumentality of architecture, it is nevertheless of the greatest vitality and richness, and, on a more intimate level, as precious an expression of artistic skill.

Features of Miniature Paintings in Medieval India

The style of the medieval Indian miniature painting was emphatically linear, the forms flat, with sharp angular contours, the faces generally in profile but with both eyes shown, one of them protruding into empty space. The colours are few, red, green, blue, yellow, and black predominating, a monochrome patch of red often constituting the background.

The most persistent feature of the medieval Indian miniature paintings are very brilliantly represented and preserved at Ajanta and is the result of a progressive simplification, abstraction, and linearization, the various stages of which are clearly demonstrable.

The line flows more smoothly, the forms are fuller and the figures begin to lose their hieratic, effigy-like character. It should be obvious that these manuscripts herald the birth of a new style, and that this new style did come into being and was flourishing by at least the early years of the 16th century. It is confirmed by the discovery of an illustrated manuscript of the Aranyaka Parvan of the Mahabharata dated A.D. 1516 and of a Mahapurana manuscript dated A.D. 1540. The promise of this new style is carried to fulfilment in the splendid Bhagavata Purana.

Development of Miniature Paintings in Medieval India

The first half of the 16h century, as far as the medieval Indian miniature painting is concerned, was a time of fervent activity. At this time Indo-Persian styles are found to exist, patronised presumably by Muslim courtly circles. In the history of India, the culture of medieval Indian miniature painting attained huge patronisation. Under the general supervision of some artists of Mughal Empire and the discerning enthusiasm of Akbar, a vigorous atelier of painters drawn from all parts of the Indian Empire grew up at the imperial court. With the development of medieval Indian miniature painting under the patronage of Mughal emperors, the trends of Mughals were included in the style and texture of paintings. The Mughal painters, most of whom were Hindus, had a subject close to their hearts, and they rose to great heights, revealing an endlessly inventive imagination and great resourcefulness in illustrating the myths.

The medieval Indian miniature painting of Jahangir"s reign (A.D. 1605-1627) departs markedly from the style of the Akbar period. The great "darbar" pictures, thronged with courtiers and retainers, are essentially an agglomeration of a large number of portraits. The compositions of these paintings are also much more restrained, being calm and formal. The colours are subdued and harmonious, as is the movement, and the exquisitely detailed brushwork is a wonder to behold. A large number of studies of birds and animals were also produced for the Emperor, who was passionately interested in natural life, and who never ceased to observe, describe, measure, and record the things rare and curious with which the natural world abounds.

To Jahangir, painting is the favourite art; he prides himself on his connoisseurship, and greatly honours his favourite painters. Even Shah Jahan was a keen connoisseur of painting, and during his time the Jahangiri traditions continued in a modified way. The compositions become static and symmetrical, the colour heavier, the texture and ornament more sumptuous. The freshness of drawing, the alert and sensitive observation of people and things, was overlaid by a weary maturity, resulting not in the representation of living beings but in effigies with masked countenances.

During the reign of Aurangzeb (A.D. 1658-1707) patronage seems increasingly to shift away from the court; works which can be identified as products of the imperial atelier are extremely few and continue the style of Shah Jahan. The large numbers of paintings assigned to the reign of Aurangzeb were executed for patrons other than the Emperor.

The Rajasthani style of Indian miniature painting is spread mainly over the various states of Rajasthan and adjacent areas. The subject-matter here is essentially Hindu, its primary concern the Krishna myth was the central element in the rapid expansion of devotional cults at this time. The style, in marked contrast to the naturalistic preferences of Mughal painting, remains abstract and hieratic, and its language, though mystical and symbolic, must have immediately evoked a sympathetic response in the heart of the Hindu viewer.

The Rajasthani style of Indian miniature painting developed several distinct schools, their boundaries seemingly coinciding with the various states of Rajasthan, notably Mewar, Bundi, Kota, Marwar, Kishangarh, Jaipur (Amber), Bikaner and yet others whose outlines are slowly beginning to emerge. During the seventeenth century, The School of Mewar was considered as the most important among the other schools, producing pictures of considerable power and emotional intensity.

The themes of Bikaner miniature painting are the same as other Rajasthani schools. The delicacy of line and colour are strong Mughal features which first become evident in painting of the mid-seventeenth century executed by artists imported from Delhi, and these features are retained to some extent even when the school begins to conform more closely to the neighbouring schools of Rajasthan.

The Deccani style of miniature painting again germinates as a combination of foreign and strongly indigenous elements inherited seemingly through the artistic traditions of the Vijayanagara Empire. This style was more poetic in mood, though similar in technique to the Mughal School. The various kingdoms of the Deccan plateau evolved idioms with their own distinctive flavour from the middle of the 16th to the 19th century. Of these, the Bijapur version, particularly under the patronage of the remarkable Ibrahim Adil Shah II (1580-1627) was marked by a most poetic quality. Important work was also done in the powerful sultanates of Golconda and Ahmednagar.

Manuscript paintings of Hoysala dynasty

The Hoysala dynasty ruled in ancient Karnataka area from the 11th to the13th centuries A.D. They constructed many beautiful temples in South India, which reflected a unique style of architecture and sculpture of them. They are still remembered for that unique feature of their art and architecture.

The Hoysala dynasty ruled in ancient Karnataka area from the 11th to the13th centuries A.D. They constructed many beautiful temples in South India, which reflected a unique style of architecture and sculpture of them. They are still remembered for that unique feature of their art and architecture.

During, the rule of the Hoysala dynasty the art of painting also reached great heights. Murals of their time cannot be seen in the temples but samples of Hoysala paintings are available in the painted palm leaf manuscripts, which they have left behind. These can be seen now at Moodhidri, a Jaina pontifical seat in Karnataka. These Hoysala paintings can be seen on very large sized palm leaves, which are now well preserved in the Moodhidri library. They are actually illustrated manuscripts and therefore contain not only paintings but also the writing of the Hoysala period. A comparative study of the writings found on these palm leaves with the inscriptions of the Hoysalas discloses that the former belong to the time of the great Hoysala ruler Vishnuvardhana and his wife, Shantala Devi who was a follower of Jainism.

One of these manuscripts painting of Hoysala dynasty is the commentary of Virasena known as Dharala. It can be traced back to the 1113 A.D. and the Yakshi Kali is seen here with her vehicle the bull and standing close by are a few royal devotees, probably the ruler, his queen and the prince, all depicted with great beauty and delicacy. The other remarkable figures in these paintings include the figures of Mahavira, in both the standing and seated postures and also one of the Parshvanatha with snake hoods above his head and sitting on a lion throne. These manuscript paintings found in this library include the `Yakshini Ambika`, who is well represented in all of Jaina art. In one of these manuscripts here, she is shown under a mango tree with her two children and the lion. One of her children is shown riding on the lion while the other is standing close to his mother.

The quality of these Hoysala paintings is really outstanding and the writings found on these manuscripts are also noteworthy. The letters are painted in a flowery style and tell volumes of the skill and patience of these dedicated artists. The manuscripts are embroidered with beautiful borders, which too have been executed with deftness and sublime beauty.

Modern Indian Paintings

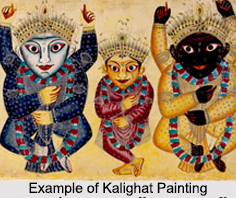

Glass Painting in India is a new concept and is extremely wonderful for its clarity and richness of colours. Patachitra flourished in the state of Odisha and is made on cloth with extremely vivid colours and mythology-based subject. Kalighat pots are another form, which are made on earthen pot or cloth. These are mainly used as wall hangings. Marble Painting is also a type of modern Indian painting which is made on exquisite marble stones. Marble paintings are mainly used for decorative purpose, especially on tabletop, furniture and flower vases. The Indian artists adopted Indian Oil painting as a unique technique of art and Raja Ravi Verma was considered to be the pioneer who made this new medium popular in India.

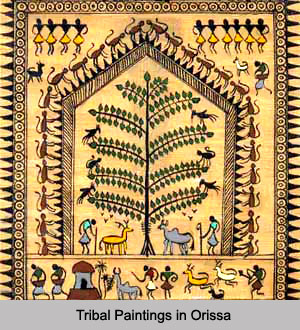

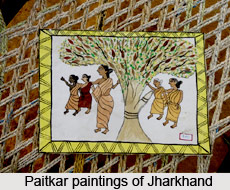

Indian Folk Painting gives a pictorial expression of village painters, which are marked by the subjects chosen from epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata and other mythological stories. Kalamkari is the form of art that involves weaving and block printing apart from painting. Silk Paintings and fabric paintings are done on cloth or different types of fabric Bengal School of Arts and Madras School of Arts were established by the British to enhance the art culture in India.