Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra are the rock-cut cave monuments, dating from 2nd century BCE, incorporating painting and sculpture, regarded masterworks of both `Buddhist religious art` and `universal pictorial art`. They are located in a wooded and furrowed horseshoe-shaped ravine. The monastic complex of Ajanta comprises numerous viharas (monastic halls of residence) and chaitya grihas (stupa monument halls), dug into mountain escarp, in two stages. The first phase is named Hinayana phase (relating to the Lesser Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, when the Buddha was venerated representatively). The second phase of excavation is named Mahayana phase (relating to the Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, which is less rigid and promotes direct cow delineation of the Buddha through paintings and carvings). This phase is sometimes referred to as the Vataka phase, after the ruling dynasty of the house of the Vatakas of the Vatsagulma branch. However, the exact date of this Mahayana chapter is a subject of intense debate among scholars; recent study puts it in 5th century. According to Walter M. Spink, a leading Ajantologist, all the Mahayana excavations were carried out from 462 to 480 CE. Modifications in Buddhist thinking in 1st century BCE had made it possible for Buddha to be consecrated and accordingly the image of Buddha as a focal point of worship became accepted, labeling the arrival of the Mahayana (the Greater Vehicle) sect. Unlike the Hinayana caves, which are almost devoid of carvings, the Mahayana caves establish a formal religious imagery.

Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra are the rock-cut cave monuments, dating from 2nd century BCE, incorporating painting and sculpture, regarded masterworks of both `Buddhist religious art` and `universal pictorial art`. They are located in a wooded and furrowed horseshoe-shaped ravine. The monastic complex of Ajanta comprises numerous viharas (monastic halls of residence) and chaitya grihas (stupa monument halls), dug into mountain escarp, in two stages. The first phase is named Hinayana phase (relating to the Lesser Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, when the Buddha was venerated representatively). The second phase of excavation is named Mahayana phase (relating to the Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, which is less rigid and promotes direct cow delineation of the Buddha through paintings and carvings). This phase is sometimes referred to as the Vataka phase, after the ruling dynasty of the house of the Vatakas of the Vatsagulma branch. However, the exact date of this Mahayana chapter is a subject of intense debate among scholars; recent study puts it in 5th century. According to Walter M. Spink, a leading Ajantologist, all the Mahayana excavations were carried out from 462 to 480 CE. Modifications in Buddhist thinking in 1st century BCE had made it possible for Buddha to be consecrated and accordingly the image of Buddha as a focal point of worship became accepted, labeling the arrival of the Mahayana (the Greater Vehicle) sect. Unlike the Hinayana caves, which are almost devoid of carvings, the Mahayana caves establish a formal religious imagery.

Artistic activity during this time did not die away, in the confines of the Gupta Empire. Distinctive Gandhara and Andhra sculpture continued to be created well into, if not all through the Gupta period. The only region beyond the fringe of the empire to give rise to something tallying intimately the metropolitan style, however was the ancient Vidarbha, now northwestern Maharsahtra, whose crafters, sculptors, stonecutters and painters were responsible for the flamboyant ornamentation of the rock-cut Buddhist monasteries in Ajanta, the spectacular U-shaped ravine in a spur of the Sahyadri Hills. It had prematurely engrossed a monastic community and two chaitya halls and three tiny viharas carved out in Satavahana times. It was in the latter half of 5th century, under the authoritative Vataka dynasty, confederate in marriage, but not subject to the Guptas, that the second and biggest phase of rock-cut architecture was kicked off in the most marvellous manner with some 23 new caves, not all finished. With the exclusion of the wrecked viharas at Bagh in western Malwa, there is no conventional rock-cut architecture within the Gupta territories during the period, the caves in Udayagiri (Vidisa), bearing mere architectural significance.

Artistic activity during this time did not die away, in the confines of the Gupta Empire. Distinctive Gandhara and Andhra sculpture continued to be created well into, if not all through the Gupta period. The only region beyond the fringe of the empire to give rise to something tallying intimately the metropolitan style, however was the ancient Vidarbha, now northwestern Maharsahtra, whose crafters, sculptors, stonecutters and painters were responsible for the flamboyant ornamentation of the rock-cut Buddhist monasteries in Ajanta, the spectacular U-shaped ravine in a spur of the Sahyadri Hills. It had prematurely engrossed a monastic community and two chaitya halls and three tiny viharas carved out in Satavahana times. It was in the latter half of 5th century, under the authoritative Vataka dynasty, confederate in marriage, but not subject to the Guptas, that the second and biggest phase of rock-cut architecture was kicked off in the most marvellous manner with some 23 new caves, not all finished. With the exclusion of the wrecked viharas at Bagh in western Malwa, there is no conventional rock-cut architecture within the Gupta territories during the period, the caves in Udayagiri (Vidisa), bearing mere architectural significance.

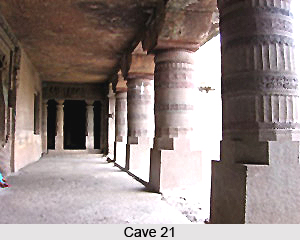

The Mahayana Caves in Ajanta are chiefly comprised in viharas, occasionally one above the other. The two chaitya halls, nos. 19 and 26, are fairly far distant from their wooden paradigms. The outstanding chaitya window, while maintaining a customary class, is imagined entirely as a means of letting in light. Reliefs of vedikas are prominently lacking from the frontages, replaced by modern-day architectural ornamentation, like the kapota, the characteristic, and at least down south, omnipresent Indian eaves moulding, with minute chaitya windows and large figurine reliefs, such as the two yaka guardians. All the viharas fundamentally share a similar plan. Cave 21 is archetypal- columned porch, three access doors, the pillars in the hall ordered in a square, and the shrine-room, anteceded by an antechamber with a pillared porch, in the middle of the back wall. The addition of antechambers and porches to no less than six of the cells, depict it to be of the most sophisticated kind. All the second-phase caves seem to have been carved out during an unusual explosion of ingenious activities and overgenerous patronage, during the latter half of 5th century.

The primary alterations in the operation and iconography of the caves consist of the initiation of a shrine-room in the viharas, the resultant wane in the magnitude of the chaitya hall, and the surfacing of a still very limited Mahayana pantheon, comprising Buddha and the large (male) Bodhisattvas, collectively with the `historical` Buddhas and other deities, already embraced during the early period. The cult-object is invariably the Buddha, very frequently in the `European` posture, along with the recurrently appearing wheel and deer of the First Sermon, worshipped by devotees on the bases. Behind Buddha, there is often an archetypal Gupta throne, together with vyala supporters and a crossbar, ending in a yali or makara heads. The yalii, more frequently termed vyiila in the north, is a griffin-like mythological beast, always depicted in a rearing posture. Bodhisattvas carrying chowries and occasionally by other standing Buddhas, who also run along the sidewalls of the shrine-chamber and even the vestibules, infrequently are bordered by Buddha. Other icons comprise the Great Miracle at Sravasti, popular in Gandhara and also at Kanheri, near Mumbai, whose abundant, but tiny second-phase caves are noteworthy less for their architecture, compared to their reliefs of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas; a huge Parinirvana and the first Avalokiteshwara, as Protector of Travellers also emerge at Ajanta, but never in a cardinal position. Stupas, or illustrations of them, are nearly missing, excluding their customary position in the chaitya halls, where they are virtually clouded by large seated Buddhas in luxuriant environs, placed on the side, facing the entryway and forming a constitutional part of the stupa.

The Buddhas, which represent the overpowering majority of the images at Ajanta, incline to be heavy and fairly lifeless; some of the astonishingly colossal statuettes are awing, however, in the dimmed light of the shrines.There are some remarkably handsome individual sculptures, such as the legendary Naga couple outside Cave 94, Ajanta, Cave 19, Nagaraja and his queen, 5th century, last quarter.

But it is for the diversity of their columns and entranceways, some comparatively plain, others depicting an almost incredible wealth of ornamental detail, that the caves are rightly far-famed, as well as for their murals- the only great body of Gupta painting t o have outlived. Here, and in Bagh, fluted columns come out for the first time, and so do many other motifs. If not in the purest Gupta élan, the Ajanta Caves, because of their number and virtually faultless state of preservation, and because of the deplorable few ruins elsewhere, alone, still picture a plethoric, diverged, and total vision of the aesthetic achievement of the Gupta period. True, for the first, but surely not the last time in the extensive history if Indian art, some of the more detailed caves can be accused with being over-cosmetic, and in this regard, a well as owing to a certain deficiency of refinement and intensity in the carving, they deviate from the Gupta fashion. If not over-cosmetic, they can nevertheless be critised, as Spink has pointed out, for the deficiency of motifs on a superior scale to serve as crucial points and for the dearth of plain surfaces, to set-off the carving. One marvellous sculpture, from as far away as the area of Nagpur, is in the Ajanta manner, which appears otherwise to have been centralized in Ajanta itself and at one or two adjacent spots. When patronage had terminated, the workers and their offsprings carried their proficiency and traditions first to Konkan, then back to Vidarbha, where they produced some even superior rock-cut monuments at Elephanta and Ellora, and ultimately to northern Karnataka.

But it is for the diversity of their columns and entranceways, some comparatively plain, others depicting an almost incredible wealth of ornamental detail, that the caves are rightly far-famed, as well as for their murals- the only great body of Gupta painting t o have outlived. Here, and in Bagh, fluted columns come out for the first time, and so do many other motifs. If not in the purest Gupta élan, the Ajanta Caves, because of their number and virtually faultless state of preservation, and because of the deplorable few ruins elsewhere, alone, still picture a plethoric, diverged, and total vision of the aesthetic achievement of the Gupta period. True, for the first, but surely not the last time in the extensive history if Indian art, some of the more detailed caves can be accused with being over-cosmetic, and in this regard, a well as owing to a certain deficiency of refinement and intensity in the carving, they deviate from the Gupta fashion. If not over-cosmetic, they can nevertheless be critised, as Spink has pointed out, for the deficiency of motifs on a superior scale to serve as crucial points and for the dearth of plain surfaces, to set-off the carving. One marvellous sculpture, from as far away as the area of Nagpur, is in the Ajanta manner, which appears otherwise to have been centralized in Ajanta itself and at one or two adjacent spots. When patronage had terminated, the workers and their offsprings carried their proficiency and traditions first to Konkan, then back to Vidarbha, where they produced some even superior rock-cut monuments at Elephanta and Ellora, and ultimately to northern Karnataka.