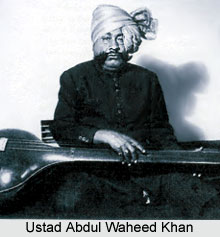

Kirana is possibly the only major gharana that, for the most part, came into being during the very early part of the 20th century. Many 20th century singers of this style trace their origin back to the legendary beenkar Bande Ali Khan. Yet another stream of the gharana claim to belong to the dhrupadic line of Naik Gopal, a singer in the Mughal court, who later adopted Islam and settled down in a village near Saharanpur. The Kirana gayaki assumed the status of a gharana, for the most part, after Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (1872-1937) and Ustad Abdul Waheed Khan (d.1949) clamed to belong to it. They were both born in village Kairana, near Kurukshetra in Haryana. The ancestors of Abdul Karim and Abdul Waheed were sarangi players. Their singing style bears, according to some music scholars like Van Meer, the strong imprint of the instrument. Sarangi players who taught vocal music placed greater emphasis, given the leanings of their instrument, on smooth voice production, tunefulness and sweetness of tone as opposed to dhrupadic gharanas, which used broad and heavy meends and gamaks. By common consent, it is held that the Kirana style demonstrates the influence of both the rudra veena and the sarangi. Abdul Waheed Khan remained a reclusive and shadowy figure as opposed to his more colourful relative, Abdul Karim. It was Abdul Waheed Khan, who had reintroduced the merukhand system, a highly cerebral mode of raaga exploration that relies on the permutation and combination of notes, into Hindustani singing, as he did the ati-vilambvit laya - the slow and meditative tempo. Karim Khan, his sister Hirabai Barodekar and Pt. Prannath were directly influenced by Waheed Khan`s style. Ustad Amir Khan, though no disciple of his, was deeply inspired by his music and went on to readapt the Waheed Khan gayaki to suit his own native genius.

Kirana is possibly the only major gharana that, for the most part, came into being during the very early part of the 20th century. Many 20th century singers of this style trace their origin back to the legendary beenkar Bande Ali Khan. Yet another stream of the gharana claim to belong to the dhrupadic line of Naik Gopal, a singer in the Mughal court, who later adopted Islam and settled down in a village near Saharanpur. The Kirana gayaki assumed the status of a gharana, for the most part, after Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (1872-1937) and Ustad Abdul Waheed Khan (d.1949) clamed to belong to it. They were both born in village Kairana, near Kurukshetra in Haryana. The ancestors of Abdul Karim and Abdul Waheed were sarangi players. Their singing style bears, according to some music scholars like Van Meer, the strong imprint of the instrument. Sarangi players who taught vocal music placed greater emphasis, given the leanings of their instrument, on smooth voice production, tunefulness and sweetness of tone as opposed to dhrupadic gharanas, which used broad and heavy meends and gamaks. By common consent, it is held that the Kirana style demonstrates the influence of both the rudra veena and the sarangi. Abdul Waheed Khan remained a reclusive and shadowy figure as opposed to his more colourful relative, Abdul Karim. It was Abdul Waheed Khan, who had reintroduced the merukhand system, a highly cerebral mode of raaga exploration that relies on the permutation and combination of notes, into Hindustani singing, as he did the ati-vilambvit laya - the slow and meditative tempo. Karim Khan, his sister Hirabai Barodekar and Pt. Prannath were directly influenced by Waheed Khan`s style. Ustad Amir Khan, though no disciple of his, was deeply inspired by his music and went on to readapt the Waheed Khan gayaki to suit his own native genius.

Early in life, Abdul Karim Khan migrated to the court of Baroda, later to the Mysore court and eventually settled down in Miraj. It would not be a hyperbole to say that the Kirana revolution was set into motion in Maharashtra and north Karnataka by Abdul Karim Khan, who conquered Western India with his lingering and deeply alluring music during the first quarter of the 20th century. His music also reflects the creative influence of the Karnatic system, especially seen in his rendition of swaras. Appreciably, he produced a whole host of towering disciples like Sawai Gandharva, Ramachandra Behrebua, Balakrishnabua Kapileshwari and Roshanara Begum who, in their turn, diffused the Kirana legacy all over the country.

Without a trace of doubt, it can be stated that Kirana has turned out to be the most popular of gharanas in the 20th century. Unlike the restrained Gwalior, the weighty Agra or the cerebral Jaipur styles, Kirana gayaki evokes the aesthetic configurations of ragas in the most stirring manner. Since it emphasized tunefulness, sweet intonation, and, importantly bhava, the everyday public took to it almost immediately. Also, it has produced and continues to produce a steady stream of singers who hold a commanding sway over lay and the conversant audiences. Bhimsen Joshi, though broadly a Kirana singer, has creatively incorporated numerous idioms from other gharanas into his gayaki. Gangubai Hangal, Firoz Dastur, Basavraj Rajguru, Manik Verma, Prabha Atre, Pt. Maniprasad, the duo Niaz Ahmed and Fayyaz Ahmed Khan, and Mashkoor Ali Khan are some of the outstanding talents of this gharana to emerge on the post-Independence scenario.

Without a trace of doubt, it can be stated that Kirana has turned out to be the most popular of gharanas in the 20th century. Unlike the restrained Gwalior, the weighty Agra or the cerebral Jaipur styles, Kirana gayaki evokes the aesthetic configurations of ragas in the most stirring manner. Since it emphasized tunefulness, sweet intonation, and, importantly bhava, the everyday public took to it almost immediately. Also, it has produced and continues to produce a steady stream of singers who hold a commanding sway over lay and the conversant audiences. Bhimsen Joshi, though broadly a Kirana singer, has creatively incorporated numerous idioms from other gharanas into his gayaki. Gangubai Hangal, Firoz Dastur, Basavraj Rajguru, Manik Verma, Prabha Atre, Pt. Maniprasad, the duo Niaz Ahmed and Fayyaz Ahmed Khan, and Mashkoor Ali Khan are some of the outstanding talents of this gharana to emerge on the post-Independence scenario.

Some of the cardinal features of Kirana gayaki are:

• Extreme tunefulness, accomplished through the prominence given to individual swaras. This extreme focus on notes gives their alaaps a solacing, emotional sonorousness which, as it were, squeezes various hues of emotions out of the matured swaras. The best samples of the gayaki are substantiated when the singers` elaborate alaap-yogya ragas like Todi, Bhimpalas, Multani, Poorya, Shudh Kalyan, Yaman and Darbari, in which thelower register predominates.

• Use of bol-alaaps, or using of the words in the song-text to develop melodic ideas, in the place of aakaar singing.

• Kirana singers often stress swara at the cost of tala and laya. Owing to this, many Kirana singers excel best in their vilambits, as opposed to singers from more rhythm-bound styles.

• Use of raaga badhat in a highly redolent manner. Badhat is the art of expatiating and developing a raaga note-by-note in an ascending and progressive fashion in extermely slow tempo. To execute this, a singer must possess a thorough command over the notes. The badhat, in the hands of virtuoso singers, takes on a reflective quality.

• Well-known exponents often treat the sthayi and antara of a composition fleetingly. The bandish does not often get the kind of meticulous attention it does in the Gwalior and Agra styles.