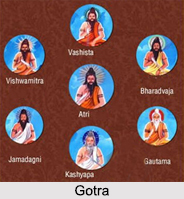

Brahmins are subdivided into seven sects, each of which has for its patron one of the celebrated Penitents. Besides this, they are split up into four classes, each class recognizing one of the four Vedas as its own. Thus there are Brahmins of the Yajur Veda, of the Sama Veda, of the Rig Veda, and of the Atharva Veda. Some are of opinion that this fourth class is extinct. But, as a matter of fact, it still exists, although there are few representatives left. They are even more exoteric than the other castes, because they allow bloody sacrifices to be offered up, and do not even draw the line at human beings. Added to this, they teach a belief in witchcraft, and any one who is supposed to possess the art earns the odious reputation of being a sorcerer. When the yagnam sacrifice takes place, it is customary for Brahmins of all four Vedas to be present. The prayers which are offered up at the sandhya are quoted from the four Vedas.

Brahmins are also distinguishable by their sect, by their names, by the marks, which they trace on their foreheads and other parts of the body. They are also distinguishable by the high priest to whose jurisdiction they are subject. The four principal sects of south Indian Brahmins can be mentioned as the Vishnavites, the Smarthas, the Tatuvadis, and the Utrassas. The distinctive mark of the Vishnavite Brahmins is the namam. Their simhasana, that is, the place where their high priest resides and their chief school, is at Hobbala in the Northern Carnatic. The Smartha Brahmins trace three horizontal lines on the forehead with sandalwood paste. Their simhasana is at Singeri in North-west Mysore. Besides these horizontal lines on the brow, the Tatuvadi Brahmins have ineffaceable marks branded on certain parts of their bodies with a red-hot iron. Their simhasana is at Sravenur. The Utrassa Brahmins draw a perpendicular line from the top of the forehead to the base of the nose.

There are also Brahmins known as Cholias, who are more or less looked down upon by the rest. They appear to be conscious of their own inferiority. This is the reason why they hold themselves aloof from other Brahmins. All menial work connected with the temples is performed by them, such as washing and decorating the idols, preparing lighted lamps, incense, flowers, fruits, rice, and other similar objects of which sacrifices are composed. In many temples even Sudras are allowed to exercise these functions, and men of this caste are always chosen for the office of sacrificer in pagodas where rams, pigs, cocks, and other living victims are offered up. No Brahmin would ever consent to take part in a sacrifice where blood has to be shed. It is perhaps on account of the work they condescend to do that the Cholia Brahmins have fallen into such contempt. According to the general view of the Brahmins, to do any work which can be left to the lowest amongst the Sudras is to put themselves on their level. This is considered as to degrade them. In any case the work of a pujari is not thought much of, and by some it is considered absolutely degrading. However, some Brahmins have to accept this task on account of their poverty, but they only do so with extreme reluctance. It is a common proverb amongst them that for the sake of one`s belly one must play many parts.

There are other Brahmins who are mockingly called meat Brahmins and fish Brahmins. As for instance, there are the Konkani Brahmins, who come from Konkana, who eat fish and eggs without the slightest compunction, but will not touch meat. And there are many Brahmins from the Northern provinces who make no secret of the fact that they eat meat. When these degenerate Brahmins visit Southern India, and their ways become known, all the other Brahmins keep them at a distance and refuse to have any dealings with them.