The Andamans were more recognisable as `Kala Pani`, but the exact reason for giving this infamous name to the islands is still in the dark. Some experts are of the view that the colour of seawaters of these islands was black either in itself or because of the reflection of the thick and dark black clouds, which almost always remained overcast. There are others who say that the stone of the hills surrounding the sea was black which by its reflection made the colour of the sea appear black.

The Andamans were more recognisable as `Kala Pani`, but the exact reason for giving this infamous name to the islands is still in the dark. Some experts are of the view that the colour of seawaters of these islands was black either in itself or because of the reflection of the thick and dark black clouds, which almost always remained overcast. There are others who say that the stone of the hills surrounding the sea was black which by its reflection made the colour of the sea appear black.

Myth behind the name Kala Pani

However, numerous scholars reject this theory, and according to them the expression `Kala Pani` has been used with reference to the Sanskrit word `Kal`, which means Time or Death. The word `Kala Pani` thus, meant the water of death or a place of death from where only the luckiest returned." The British, immediately after the establishment of penal settlement in the Andamans in 1858, also referred these islands as existing across the `Black Water`. Aden, an island in the Arabian Sea where Vasudeo Balwant Phadke was transported, too, was called `Kala Pani`.Obviously, therefore, the name `Kala Pani` was given to these penal settlements, which were far removed from the mainland of the country by long stretch of seawaters where hardcore criminals were to be transported from the country. The jail authorities there were at liberty, rather, were instructed by the British government to treat the prisoners with extreme unkindness and from where only the luckiest could return.

Purpose of Kala Pani

`Kala Pani` or `Black Water` virtually meant cruel and ruthless treatment to the prisoners till death. A sentence of deportation to `Kala Pani` meant a warrant for throwing the prisoner in living hell to face heard or unheard trials and tribulations and to lead a life of a beast or even worse than that. Expatriation to `Kala Pani` for life was worse than death penalty. The Indian revolutionaries were doomed to `Kala Pani` to undergo these harsh punishments but they in turn immortalised these islands by their selfless sacrifices.

Although the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are among the world`s most beautiful islands and neither the soil, nor the water of these islands is black, but the British government had created a situation to call these islands as `Kala Pani` because of the inhuman barbarisms inflicted on the patriot prisoners fighting for the liberation of their motherland who were transported from the mainland and gaoled in these islands. The term "Kala Pani" is interwoven with the trials and tribulations faced by the brave political prisoners in Cellular Jail and of those freedom fighters of the first war of independence who were brought to these islands to lead a `hell like life".

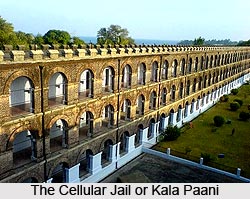

History and Foundation of Cellular Jail

The Cellular Jail, colloquially known as "Kala Pani ki Saja" due to the harrowing sufferings endured by its inmates and the stringent punishments inflicted upon those who dared to resist, stands as a testament to a dark period in Indian history during the colonial era. The historical backdrop and establishment of the Cellular Jail shed light on the origins of this infamous moniker attributed to the Andaman Islands` penal institution. While the British began utilizing the Andaman Islands as a penal colony shortly after quelling the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (commonly referred to as the Sepoy Mutiny), the groundwork for the construction of the Cellular Jail was laid in the year 1896. The outcome of what is recognized as India`s First War of Independence ultimately favored the British, resulting in the suppression of the rebellion through the execution of numerous insurgents and the exile of the remaining rebels to the Andaman Islands for a lifetime of confinement.

The incarcerated rebels, numbering in the hundreds, found themselves under the custody of jailer David Barry and military doctor Major James Pattison Walker upon their arrival on the island. Notably, a significant incident occurred in March 1868 when 238 prisoners endeavored to escape from the jail, only to be apprehended in April of the same year. Subsequently, 87 of these escapees met their fate on the gallows. As the Indian struggle for independence gained momentum in the late 19th century, an increasing number of patriots who opposed British rule were convicted and subsequently dispatched to the Andaman Islands from British-controlled territories in India and Burma.

The inmates` dread of the unforgiving waters surrounding the Andamans and their utter isolation from the mainland effectively quashed any prospects of escape. Consequently, the island evolved into a fitting locale for the British authorities to administer punitive measures to those who fought for India`s liberation. The prisoners, subjected to chains, were coerced into laborious construction tasks involving the erection of structures, prisons, and harbor facilities—endeavors aimed at furthering British colonization efforts in the Andaman Islands.

With the surge of the Indian independence movement in the latter part of the 19th century, the influx of prisoners necessitated the establishment of a high-security detention facility. The concept of a "penal stage" within the transportation sentence, suggested by Sir Charles James Lyall, the home secretary of the British Raj, and A. S. Lethbridge, a surgeon within the British administration, dictated that a prisoner would undergo rigorous treatment for a specific period subsequent to deportation to the Andamans. This concept culminated in the construction of the Cellular Jail, a project that commenced in 1896 and reached completion in 1906.

During the year 1942, the Japanese forces managed to overpower the British presence in the Andaman Islands, subsequently expelling them from the region. A notable occurrence during this period was the visit of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to the Andaman Islands. Following the conclusion of the Second World War in 1945, British control over the islands was restored. This marked yet another significant chapter in the complex history of the Cellular Jail and the Andaman Islands as a whole.

Life as a Convict in Kala Pani

The existence of a convict`s life within the confines of the Kala Pani, as described in the Andaman and Nicobar Gazetteer of 1908, was characterized by a structured progression of stages. Upon entering the Jail, convicts endured a rigorous discipline for the initial six months, during which the workload was not overly burdensome. Subsequently, they were relocated to an associated Jail for a duration of 18 months, where the labor became arduous while the discipline slightly eased. Over the subsequent three years, convicts resided in barracks, adhering to a nocturnal schedule and engaging in supervised labor. The labor undertaken during this period garnered rewards, with an assessment of their capabilities conducted concurrently.

In the ensuing five years, convicts continued to engage in labor, yet they became eligible for minor supervisory roles and less strenuous forms of work. Moreover, a modest allowance was granted, intended for minor indulgences or savings within the special Savings Bank. Upon completing a decade of transportation, a convict was granted a "ticket to leave" – a means to become self-supporting. In this state, they were afforded the opportunity to earn their livelihood in a village, engaging in activities such as farming, cattle rearing, and even establishing familial ties through marriage or the reunion of their families.

The Kala Pani ki Saja, a term invoking fear and trepidation, cast a daunting shadow even upon the most hardened criminals. It was widely believed that once subjected to the punishment of Kala Pani, an individual would never return. The prison garnered infamy for incarcerating numerous prominent Indian freedom fighters and political activists during the fervent struggle for India`s liberation. It was often referred to as the "Bastile of India," bearing witness to the enduring struggle for freedom waged by individuals held in captivity by foreign rule.

Treatment in the Prison

Treatment within the prison was administered with a regimented approach that often varied based on age, literacy, and the category of offense committed. Specifically, individuals below the age of twenty were exempted from engaging in strenuous manual labor. Those with literacy skills were assigned to tasks within the press, while assignments were determined according to the physical capabilities of each prisoner. Political prisoners were subject to distinct treatment measures.

Convicts incarcerated within the Cellular Jail were assigned a range of tasks, including:

Cane and bamboo work

Operating coconut and mustard oil mills

Husking and opening coconuts

Drying copra

Crafting hooka shells

Coir and sisal pounding

Rope production

Carpet weaving

Towel weaving

Crafting coir and sisal hemp mats

Cleaning mustard seeds

Blanket mulling

Engaging in gardening activities

Participating in hill cutting and swamp filling when required

Miscellaneous duties such as conservancy and drain cleaning within the jail vicinity

Serving as hospital ward coolies, undertaking sweeping tasks, and engaging in clerical work within the jail office.

The stringent treatment extended to the prisoners encompassed the nighttime as well. The warden enforced a policy wherein prisoners were prohibited from addressing their physiological needs during the twelve hours of the night. The chamber pots provided were so diminutive that their use was limited. To attend to nature`s call, a prisoner was required to approach the Jamadar, often involving a demeaning process of supplication. Refraining from this during the night became a necessity. Should a prisoner encounter an unexpected ailment during this time, seeking assistance was fraught with challenges. Reports to the doctor were rarely filed or, in the rarest of instances, only one report out of a hundred was submitted. These reports were then submitted to Mr. Barry, whose actions were dictated solely by his discretion. This protocol subjected prisoners to great distress during the night, particularly when faced with sudden, abnormal ailments.

Morning hours saw Mr. Barry presiding over evaluations of prisoners` conditions. Stern rebukes were administered to warders and Jamadars for perceived lapses in their duties. Prisoners were even subjected to cross-examinations by Mr. Barry himself. If a prisoner pleaded for the call of nature, Mr. Barry often responded with harsh beatings. In instances where a convict demonstrated courage by responding that such calls were unavoidable, the Jamadar would deliver a slap to the face while reprimanding the prisoner for insolence. Generally, stern words were the prisoners` only reprieve. However, Mr. Barry frequently relegated prisoners to the grinding mill as a punitive measure.

This treatment regimen painted a picture of rigorous discipline and strict control, where physiological needs were subjected to unwavering authority and prisoners navigated the constraints of a rigid system within the confines of the Cellular Jail.

The Cellular Jail or the place of Kala Pani stands today as a silent observer of the inhumane tribulations endured by the valiant patriots and freedom fighters who were confined within its cells. This historic narrative of struggle has been translated into a Sound and Light Show by the Department of Tourism, which recounts the island`s history and the jail`s legacy as if spoken through the venerable "Peepal Tree," a long-standing sentinel within the jail`s precincts. The brave souls relinquished their lives, becoming victims of the tyranny and cruelties propagated by both British and Japanese authorities. The sheer magnitude of the edifice instills a sense of apprehension within observers while simultaneously evoking profound respect for the indomitable spirit that prevailed within its walls.