Instruments in Hindustani Classical Music are of various types. The instruments that are used in Hindustani music are all played according to a sequence. Several of the musical principles that have been developed in alap, dhrupad, and khayal are found contained in the alap-jor-jhala-gat sequence of instrumental performance. The instrumental alap is much like the alap that precedes a dhrupad. It is un-metered, slow, and searching out the chosen raaga. Slight differences can be attributed to the differences in the performing medium. On a stringed instrument in particular, the prolonged, intense Sa with which a dhrupad alap begins cannot be produced because the string too quickly ceases to vibrate. Many instrumentalists begin their alap by running a finger down the sympathetic strings in glissando. They then play a couple of phrases in the middle and upper registers to show off the outlines of the raaga before settling into the traditional alap. In addition, the exploration of the lower register is sometimes more prolonged in an instrumental performance than in a vocal one, again because of the nature of the medium.

Instruments in Hindustani Classical Music are of various types. The instruments that are used in Hindustani music are all played according to a sequence. Several of the musical principles that have been developed in alap, dhrupad, and khayal are found contained in the alap-jor-jhala-gat sequence of instrumental performance. The instrumental alap is much like the alap that precedes a dhrupad. It is un-metered, slow, and searching out the chosen raaga. Slight differences can be attributed to the differences in the performing medium. On a stringed instrument in particular, the prolonged, intense Sa with which a dhrupad alap begins cannot be produced because the string too quickly ceases to vibrate. Many instrumentalists begin their alap by running a finger down the sympathetic strings in glissando. They then play a couple of phrases in the middle and upper registers to show off the outlines of the raaga before settling into the traditional alap. In addition, the exploration of the lower register is sometimes more prolonged in an instrumental performance than in a vocal one, again because of the nature of the medium.

The ideal three-octave range of a vocalist is considerably easier to attain on sitar and sarod, where the range is provided on the strings in vocal alap. The point in the instrumental alap where the performance begins to be more rhythm-oriented and where the speed accelerates noticeably is the jor. A pulsation becomes obvious, too, although it is not consistent.

Later, toward the end of the un-metered portion of the performance, the artist refers constantly to the drone pitch (by using the drone / rhythm strings on stringed instruments) and maintains a rapid, constant pulsation by plucking (or tonguing, on a wind instrument) each pitch separately. This articulation and this section of the performance are called jhala. The melody of the gat to follow is frequently foreshadowed in this jhala, as melody pitches stand out from the drone pitches in the rhythmic drive. With a tremendous climax of speed and virtuosity, the performer brings the un-metered portion of the performance to an end with jhala.

Often, there is a short break between jhala and the gat as the drummer and instrumentalists check their tuning. When all is ready, the instrumental soloist begins a composition, called a gat. Like the other types of Hindustani compositions, most gats begin not on count 1 but on a previous count. This can be khali , or even on count 12 if in tintal. (Other gats begin right on count 1). When the drummer hears the gat beginning, he plays a fast flourish, which he times perfectly to meet the soloist at count 1. The metered portion of the performance has begun.

Often, there is a short break between jhala and the gat as the drummer and instrumentalists check their tuning. When all is ready, the instrumental soloist begins a composition, called a gat. Like the other types of Hindustani compositions, most gats begin not on count 1 but on a previous count. This can be khali , or even on count 12 if in tintal. (Other gats begin right on count 1). When the drummer hears the gat beginning, he plays a fast flourish, which he times perfectly to meet the soloist at count 1. The metered portion of the performance has begun.

Occasionally, the soloist challenges his tabla player at this moment by refraining from telling him in advance which tala the gat will be played in. Furthermore, the soloist has probably chosen a difficult or rare tala, such as one with 11 counts or one with 13 counts. Challenges such as these are part of performance practice in Hindustani instrumental music.

There are two basic types of instrumental gats: Masit Khani gats and Reza Khani gats. Masit Khani gats are in slow or medium speed, and Reza Khani gats are in medium or fast speed. In performances, they are often linked as a pair- slow to fast- as the two types of khayal are linked. Most gats are only one tala cycle long and function both melodically and metrically in the performance. A gat`s melodic shape is determined partly by the structure of the particular raga being played, but various compositional means are employed to show off the structure of the tala cycle, as well. One of the compositional elements of sarod and sitar gats is stroking patterns- patterns of inward strokes (called da), outward strokes (ra), and a quick succession of in and out (dira). The ideal Masit Khani gat, for example, has the following basic pattern: The stroking pattern divides the tala cycle into two equal parts: counts 12 to 3 (past sam) and counts 4 to 11.The rhythm and melodic contour of a gat are additional compositional elements that may be used to delineate the tala structure. Beyond the initial playing of the gat melody that begins the gat portion of the performance, the artists proceed quickly to improvisation. The gat returns in part or in full at cadences.

A striking difference between a sarod or sitar gat performance and a khayal performance is the amount of interplay between the melody soloist and the drummer. In one possible relationship, they alternate between the roles of soloist and timekeeper: either the drummer plays theka while the melody soloist improvises, or the melody soloist plays the gat while the drummer takes the spotlight. The melody soloist initiates the relationship. In the gat portion of a performance, audiences are likely to hear an exchange between drummer and melody soloist that is a challenge to imitation. This exchange is called jawab-sawal (question-answer). The melody soloist will play a phrase and challenge the drummer to reproduce it rhythmically and even melodically to some extent. (This is different from the exchange mentioned in the previous paragraph.) During this type of relationship, both musicians keep tala in their head. The amount of attention that will be focused on the drummer depends on the performance custom of the melody soloist. Some prefer an accompanist-soloist relationship; others prefer a more equal partnership.

A striking difference between a sarod or sitar gat performance and a khayal performance is the amount of interplay between the melody soloist and the drummer. In one possible relationship, they alternate between the roles of soloist and timekeeper: either the drummer plays theka while the melody soloist improvises, or the melody soloist plays the gat while the drummer takes the spotlight. The melody soloist initiates the relationship. In the gat portion of a performance, audiences are likely to hear an exchange between drummer and melody soloist that is a challenge to imitation. This exchange is called jawab-sawal (question-answer). The melody soloist will play a phrase and challenge the drummer to reproduce it rhythmically and even melodically to some extent. (This is different from the exchange mentioned in the previous paragraph.) During this type of relationship, both musicians keep tala in their head. The amount of attention that will be focused on the drummer depends on the performance custom of the melody soloist. Some prefer an accompanist-soloist relationship; others prefer a more equal partnership.

The speed accelerates throughout the gat improvisation and the performance arrives finally at a breathtaking jhala section towards the ending. The jhala is metered on this occasion, but the same driving rhythm heard in unmetered jhala is obtained by constant articulation of pitch Sa.

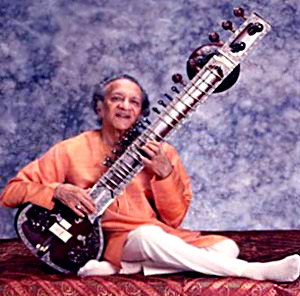

This type of instrumental sitar and sarod alap-jor-jhala-gat sequence is probably the best known of all Indian music due to the popularity of some of India`s finest instrumentalists: sitarist Pt Ravi Shankar, sarodist Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, and drummers Alla Rakha and Chatur Lai. Sitarist Ustad Vilayat Khan is known for a somewhat different style of this type of performance. His style is said to be gayaki (vocal) style. That is, he tries to reproduce on sitar the legato style of vocal music.