Mughal culture as a variant of the international Islamic culture, which mainly focused on Persian language and Safavid culture as central elements in the Mughal nobility`s own identification. Indeed, command of Persian plays a large part in assessments of Urdu literature specially the poems. Even as recently as 1973 the critic Ahmed Ali praised Atish`s poetic diction in spite of an occasional vulgarized use of Persian idiom, and it was also noted earlier that Mohammad Azad indulgently overlooked Atish`s imperfect understanding of Persian in favour of his colloquial diction. Even though Nasikh was known for his erudition in Persian and Arabic language, Azad had cast aspersions on his knowledge of the two languages by writing that, of course since "Shaikh Sahib" had attended the Firangi Mahal he must have benefited somewhat from proximity to his revered and learned teachers.

Mughal culture as a variant of the international Islamic culture, which mainly focused on Persian language and Safavid culture as central elements in the Mughal nobility`s own identification. Indeed, command of Persian plays a large part in assessments of Urdu literature specially the poems. Even as recently as 1973 the critic Ahmed Ali praised Atish`s poetic diction in spite of an occasional vulgarized use of Persian idiom, and it was also noted earlier that Mohammad Azad indulgently overlooked Atish`s imperfect understanding of Persian in favour of his colloquial diction. Even though Nasikh was known for his erudition in Persian and Arabic language, Azad had cast aspersions on his knowledge of the two languages by writing that, of course since "Shaikh Sahib" had attended the Firangi Mahal he must have benefited somewhat from proximity to his revered and learned teachers.

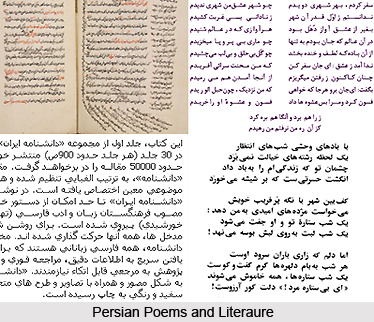

The significance of Urdu literature`s connection to other literary traditions must not be underestimated. The aesthetics of ghazals are direct descendants from those of Persian poetry; and modern Urdu criticism was founded upon a combination of the inheritance from Persian and principles borrowed from English literature. These connections greatly influenced various writers and critics, inducing a two-fold cultural conflation.

Conflict of Indo-Persian Culture in Urdu Literature

While Urdu literature is considered as an essentially Indian cultural product, it does reflect the profound impact of Persian culture on Indo-Muslim society. It eventually came to pass, in the context of cultural authority, that Persian served as a convenient evocative term for Urdu critics and social historians, and the term "Mughal" another. These two streams of authority can be seen in the struggles to which the Delhi-Lucknow rivalry gave rise. By the 1800s, Muslim culture in India had experienced about a century`s development in the sole hands of a group of artists bred on Indian soil. The waves of Persian migration which had rolled into Mughal Empire India since the fifteenth century had now begun to subside. Most of the cultural and ruling elite, though descended from Iranians, Afghans and Turks, were purely Indian in experience.

That they do not appear to have acknowledged differences between how Iranians and Indian Muslims viewed Persian culture in India suggests that Urdu critics of the nineteenth century were indeed the products of a cultural conflation. If fact, it suggests that they may not have been aware of differences between Persian culture in Iran and Persian culture elsewhere. Certainly, an integrated view of these distinctions could not have been as accessible to Urdu critics of the last century as it is to us in the late twentieth century.

Lucknow`s ruling family represents a case of Persian descendants who were completely Indian in experience. When they broke away from the nominal control of the Mughal Empire in 1818 to take on the title of "Kings" in Avadh, they may have been anxious to establish some alternative source of legitimacy. Until then their continued claim of allegiance to the Mughal throne had carried with it a vicarious cultural legitimacy. Now, in the new absence of the legitimacy and authority which had come hand in hand with position at the Mughal court, they began to draw upon Persian connections.

Urdu was the paramount language in Lucknow, especially the literary language of the new markar, while the official court language in Mughal Delhi had remained Persian throughout the 1700s. Although it became all the rage to compose poetry in the vernacular during this time, there were few poets of Delhi who wrote exclusively in Urdu: they still saw their main avocation as Persian composition.

By 1800 the Lakhnavi populace was a quarter-century old, and the need for "refinement" of Urdu as a literary language began to be expressed by poets like Insha and, later, Nasikh. In striving toward that "refinement," the masters worked to apply the principles of Persian, since Persian provided their literary models. Here again the Indo-Persian cultural blend was acted out: the role of Persian culture in Indo-Muslim society may have become more esoteric, but Persian language itself had never lost its cultural authority.