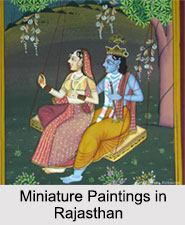

Influence of Food in Bengali Patua work is rather immense. It is in fact an illustration of the recurrence of food as both a theme and the raw material in indigenous Bengali art. Traditionally, every village had a resident patua whose depiction of divine figures or scenes from myths, epics and narrative poems often adorned the walls of huts or substituted for images in the household niche reserved for worship. The illustrations were remarkable for their bold line drawings and vivid use of pure unmixed colours. The tradition of patachitra or pat (as the illustrations were called) is very old and exists throughout the Indian subcontinent. Some scholars consider the Bengali patuas to have been influenced by the miniature paintings that flourished under the Rajput and Mughal rulers in northern India. Whatever the influences, over the course of several centuries, they created a unique and unmistakable imprint that cannot be seen in any other region.

Influence of Food in Bengali Patua work is rather immense. It is in fact an illustration of the recurrence of food as both a theme and the raw material in indigenous Bengali art. Traditionally, every village had a resident patua whose depiction of divine figures or scenes from myths, epics and narrative poems often adorned the walls of huts or substituted for images in the household niche reserved for worship. The illustrations were remarkable for their bold line drawings and vivid use of pure unmixed colours. The tradition of patachitra or pat (as the illustrations were called) is very old and exists throughout the Indian subcontinent. Some scholars consider the Bengali patuas to have been influenced by the miniature paintings that flourished under the Rajput and Mughal rulers in northern India. Whatever the influences, over the course of several centuries, they created a unique and unmistakable imprint that cannot be seen in any other region.

The preparation of paper and colour for painting shows again how integrated rice was with the expression of the artistic impulse of Bengal. Glue, prepared by boiling crushed rice, was first applied to individual sheets of paper. Ten or twelve such sheets were successively glued together to form a thick pad, which was further hardened by being pressed over a wooden board by a stone pestle applied like a rolling pin. Once the pad was dry and stiff, the patua could start the painting. The bold, vibrant colours used in illustrations were derived from natural substances like indigo, cinnabar, chalk, vermilion, soot from an oil lamp and burnt rice, crushed and made into a paste with water. Each of these was carefully mixed in a solution made from the gum of tamarind or a fruit called bel.

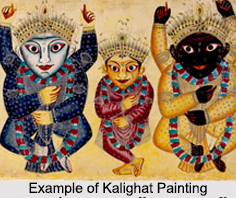

Kalighat Pats

The subjects favoured by most rural illustrators were, as demanded by their clients, mostly sacred- scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, episodes from the life of Lord Krishna or from the life of Sri Chaitanya. But one branch of this art shows considerable urban influence and was highly secular in content, rich in acute social commentary. This is the body of indigenous paintings known as the Kalighat pats, produced by illustrators who settled around the Kali temple in Kalighat, Kolkata.

Although the temple was built in 1809, the site had been dedicated to the Goddess Kali since the fifteenth century. Rural patuas, looking for more work, started settling there from the middle of the eighteenth century. Most were from the district of Medinipur in Bengal. As the city of Kolkata grew under the British and its Bengali residents developed the distinct babu culture, the illustrators gave full play to their artistic imagination by depicting different aspects of urban life. Eventually, their work spawned the famous woodcut prints that vividly illustrated the genre of cheap romantic thrillers published by the local Battala press

Although the temple was built in 1809, the site had been dedicated to the Goddess Kali since the fifteenth century. Rural patuas, looking for more work, started settling there from the middle of the eighteenth century. Most were from the district of Medinipur in Bengal. As the city of Kolkata grew under the British and its Bengali residents developed the distinct babu culture, the illustrators gave full play to their artistic imagination by depicting different aspects of urban life. Eventually, their work spawned the famous woodcut prints that vividly illustrated the genre of cheap romantic thrillers published by the local Battala press

Theme of Kalighat Pats

The Kalighat paintings project the image of a society in flux, where the men, who were in the external world, were caught between the servility demanded by their colonial masters and the libertine pursuit of sensory pleasures. Amoral attitudes and double standards were highly prevalent. On the other hand, women, imprisoned in the home, continued the rural, ritualistic traditions of their forebears. Many of these rituals involved the elaborate preparation of food and the Kalighat artists frequently focused on that. Ceremonies like jamaishashthi (honouring the son-in-law) or bhaiphonta (sisters praying for the welfare of their brothers and feeding them a special meal) are common subjects of pats. Inevitably, they centre on food-a large plate of rice and condiments surrounded by numerous bowls containing an array of fish, meat, legumes, vegetables, chutneys and desserts. But beyond the literal depiction lies the significance of the effort behind these elaborate, multi-course meals (the ideal feast was supposed to consist of sixty-four dishes). For the son-in-law, the effort was in the nature of a tribute, an offering made to the person who held the happiness, comfort, even the life of a beloved daughter in his hands. In the case of the brother, it was an act of appeasement, the sister praying to avert the attentions of the god of death. In a male-dominated society, a brother`s death was an evil to be feared; no one cared about the sister`s well-being.

Even more remarkable are the pats with vivid, intimate close-ups conveying specific messages. A man`s hand clasps huge blue-black freshwater prawns, a medium-sized carp and a lau or bottle gourd. The combination of gourd and prawns, which will produce the classic lau-chingri, is a commentary on the Bengali preoccupation with food, a fact well-noted in other parts of India. Another drawing, titled `Biral Tapaswi` (the ascetic cat), shows up the hypocrisy of many urban Bengalis who hid their dissolute habits under a surface sobriety. The image is that of a cat whose forehead and nose bear the markings typical of holy ascetics who espouse a strictly vegetarian diet. But in its mouth, the cat holds a large prawn, which, obviously, it plans to devour in secrecy.

Thus the influence of food in Bengali Patua work has been immense, be it in the form of raw material or as a source of inspiration as theme of the paintings.