Introduction

History of Indian wildlife is a significant mix of diverse species, forests, land, events, exploitation, protection of species and populations. This history relates to nature, how people feared and respected it and then eventually tried to dominate it. It is believed that history of wildlife is often associated with long names and dates, news of rare species and conflicts over threatened habitats. This history also relates to the high scale stripping of the natural vegetative cover over the past two centuries. It is important to note that even though much of the vegetative cover has vanished, a large amount still remains.

History of Indian wildlife is a significant mix of diverse species, forests, land, events, exploitation, protection of species and populations. This history relates to nature, how people feared and respected it and then eventually tried to dominate it. It is believed that history of wildlife is often associated with long names and dates, news of rare species and conflicts over threatened habitats. This history also relates to the high scale stripping of the natural vegetative cover over the past two centuries. It is important to note that even though much of the vegetative cover has vanished, a large amount still remains.

Ancient History of Indian Wildlife

Wildlife in India has been surviving since the Vedic period and a record of the existence of nearly 250 species of birds at the time have been obtained. This period ranges from 1500 BC to 500 BC. Information about wildlife belonging to this period is present in the medical treatises of Sushruta and Charaka. The blackbuck was quite common in `Aryavarta` or the land of the Aryans, who were present in the northern part of the Vindhya Mountains and even those which extended till the south. The house crow and Indian koel were commonly noticed at that time. The 2000-year-old `Gajashastra`, which was written in Pali script, contains references to the training of captured elephants. Several animal bones, which existed prior to 1700 BC, have been discovered at the sites of Indus Valley Civilization. More specifically, the bones of elephants, chital, jackal, hare and rhinoceros have been discovered at the site. Clay tablets of this period depict species of elephant and rhinoceros, which have presently been labeled as "extinct". Elephants are the earliest known Indian animals, which were employed to be mounted upon during battles. They acted as raised platforms during hunting and also as a status symbol during Harappan Civilization. A tiger seal as old as 3000 BC has been unearthed from Harappa. An animal known as `Zebu` completely disappeared from the Indus basin and western India, probably on account of breeding with domestic cattle and the consequent loss of natural habitat.

An animal known as `Zebu` completely disappeared from the Indus basin and western India, probably on account of breeding with domestic cattle and the consequent loss of natural habitat.

During the 3rd and the 4th centuries BC, the rulers of Maurya dynasty altered their attitudes towards wild beasts, in their attempts to protect animals of forests. Vast number of lions, tigers and elephants were protected by the Mauryas. Elephants were emphasized upon the most, as they served innumerable purposes for the rulers, particularly during wars. Along with horses, elephants were treated royally. Elephants and horses had played crucial roles in the defeat of Alexander`s general, Seleucus. Kautilya`s `Arthashastra` provide information about them. After embracing Buddhism, King Ashoka had implemented laws for the conservation of wild animals. Edicts of Ashoka claim that he made a rule, according to which people would be fined 100 `panas` for poaching deer inside the royal hunting grounds.

Medieval History of Indian Wildlife

Jahangir and Babur were amongst the Mughal emperors, who made regular observations of wildlife in their journals. Certain books suggest that lesser rhinoceros survived during the time, especially near Mahanadi River and Sunderbans, close to Bengal and also near Rajmahal Hills, close to Ganges River. Babur was fond of hunting and many animals were killed near Kolkata. Jahangir recorded the number of animals hunted by him. It was found that from his age of 12 to 48, he had hunted about 28,532 animals. About 35 swamp deer or `mhaka`, 889 blue bulls, 86 tigers, 9 foxes, otters, hyenas, leopards, etc were the victims. It is believed that Ustad Mansur, who was a court artist of Jahangir in the 17th century, had painted a wonderful portrait of a Siberian crane. A species namely, dodo was introduced in his court by the Portuguese, who were governing Goa at the time. An unsigned painting of this creature is said to have been accomplished by Mansur.

A species namely, dodo was introduced in his court by the Portuguese, who were governing Goa at the time. An unsigned painting of this creature is said to have been accomplished by Mansur.

Modern History of Indian Wildlife

During the pre-colonial and post-colonial eras, various species of rare insects were brought to India, free of cost. Two clear events mark the history of Indian wildlife. Firstly, the impacts of the British, whose intrusions into the world of the wild were far more extensive than those of its predecessors. History of Indian wildlife shows that princes and middle-class Indians were contended with the British, as far as hunting was concerned. As per historical records, the royal hunt became an indispensable part of every ruler`s skill range and was adopted sincerely by the British rulers. The second event was the unleashing of the widespread destructive forces, including the state-sponsored slaughtering of certain wild animals and the harnessing of forest for industrial raw materials and military supplies. Another event in the history of Indian wildlife was the creation of legal and governmental apparatus to administer large stretches of forest, eventually totaling around a fifth of India`s total land area.

With independence, a dominant group emerged with a kinder and gentler approach to nature in India. However, the legacy of the control system remained, despite major changes. The vast history of Indian wildlife signifies that much of the future relies on the reforms or restructures of the system and protection of nature`s heritage.

Indian Wildlife under Mughals

The Mughals presided over a territory of great diversity, both ecological and cultural. But the extension of agriculture was at the heart of the ability of the empire to survive and thrive. Despite war booties and tribute, the total amount of grain grown by the cultivator was what guaranteed the splendours of court life. Peasants hacking down the jungle to make way for farmland were rewarded by their revenues being written off for the first few years. In practice, the rulers drew on a range of skills and forms of wealth other than cash revenues. The gifts given as tribute provide an insight into the wealth of the wildlife of that era. Elephants were received as tribute from some North Indian villages in lieu of cash; musk from the musk deer was received from the Mishmi hills in the north-east.

The Mughals presided over a territory of great diversity, both ecological and cultural. But the extension of agriculture was at the heart of the ability of the empire to survive and thrive. Despite war booties and tribute, the total amount of grain grown by the cultivator was what guaranteed the splendours of court life. Peasants hacking down the jungle to make way for farmland were rewarded by their revenues being written off for the first few years. In practice, the rulers drew on a range of skills and forms of wealth other than cash revenues. The gifts given as tribute provide an insight into the wealth of the wildlife of that era. Elephants were received as tribute from some North Indian villages in lieu of cash; musk from the musk deer was received from the Mishmi hills in the north-east.

Further, during the Mughal period, there were vast pastures for cattle, firewood was plentiful in most parts of the empire, and many areas had higher rainfall levels comparatively. It is quite possible that more land was forested than was once thought to be the case. Even in the core of the empire only one out of four acres was under the plough. People were even fewer in areas of high rainfall, in dense forests or in places plagued by crop-raiding elephants. Forests were undoubtedly being cleared, but in large regions of Central India and the Chota Nagpur Plateau, uncultivated lands and forest covered a greater expanse than fields and farms. Land was more abundant than labour. The forests and savannahs were the sites of hunts, great and small, potential revenue-yielding arable land or simply an impediment to military operations. It is believed that the wild spaces could be a hunting ground where prior imperial rights were asserted and enforced. Certain lands had to be set aside to ensure the success of royal hunts. Unlike the elephant forests of the Mauryas, the Mughal locations are easy to map and it is clear there were a range of imperial hunting grounds in different provinces. In the Mughal era, in times of war, denudation was a routine affair.

The picture of Mughal India in terms of the human impact on nature emerges more clearly if contrasted with experiences of contemporary Europe. In that period there existed much larger stretches of contiguous habitat even for the larger land mammals. The Mughals took aboard older traditions of the hunt but added to it significant new features. Habitat of large mammals such as the elephant and the rhino was broken up were harbinger of larger changes in the land. Falconry, cheetah coursing, horsemanship and archery remained the main pastime of landed aristocracy across much of North and Central India for much longer. Mughal Rulers commissioned paintings and portraits celebrating victory over the beasts of the forests.

Indian Wildlife under British

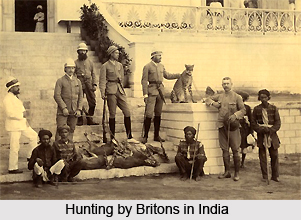

Indian wildlife under British included some dangerous and man-eating animals. During the British rule, several bounties were given out in various provinces to eliminate the dangerous beasts and poisonous snakes. Eventually, a centralised administrative machine began to oversee such efforts, resulting in a veritable war against errant species. Such practices were new to India as no previous ruler had ever attempted to exterminate any species. Within two decades of defeating the rulers of Bengal in the historic Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British declared special rewards for any tiger killed. Other legitimate targets included large herbivores like the elephant, the wild buffalo and the great Indian one-horned rhinoceros. Further, rulers who preceded the British had often asked their local officials to eliminate tigers and bandits. The idea was to help push back the forests. It was part of the constant tug of war between axe and plough on one hand and the incredible ability of natural vegetation to spring back.

Indian wildlife under British included some dangerous and man-eating animals. During the British rule, several bounties were given out in various provinces to eliminate the dangerous beasts and poisonous snakes. Eventually, a centralised administrative machine began to oversee such efforts, resulting in a veritable war against errant species. Such practices were new to India as no previous ruler had ever attempted to exterminate any species. Within two decades of defeating the rulers of Bengal in the historic Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British declared special rewards for any tiger killed. Other legitimate targets included large herbivores like the elephant, the wild buffalo and the great Indian one-horned rhinoceros. Further, rulers who preceded the British had often asked their local officials to eliminate tigers and bandits. The idea was to help push back the forests. It was part of the constant tug of war between axe and plough on one hand and the incredible ability of natural vegetation to spring back.

Part of the British animosity to the forest and its wild inhabitants stemmed from the situation in Bengal, the very first region of India they conquered. Much of eastern India suffered a major famine around 1770. As a result of the massive mortality, large areas of farmland remained uncultivated and reverted to jungle during the British era. The secondary growth was probably ideal habitat for deer and wild boar and their chief predator, the tiger. Bounties aimed to eliminate cattle-predatory tigers. Fewer tigers meant more cultivation and more revenue. Unprecedentedly, larger rewards were given out for killing tigresses, and special prizes for finishing off cubs. Similar techniques had been honed to perfection in the British Isles whose prime predator, the wolf, had already been killed off by the time the British founded an empire in India.

Moreover, Colonial strictures against the annual hunts of the Santhal tribes removed a major check on wild animal populations. The disarming of peasants in the aftermath of the rebellion of 1857-58 often deprived them of the means of effective self-defence against wildlife. Various local systems of control and self-defence were being replaced by a new regime that sought to resolve conclusively the issue of human-wildlife relations. In the 1870s, local practices across British ruled territories were evaluated and the Government of India worked hard to calculate the best method of exterminating wild animals. Over 80,000 tigers, more than 150,000 leopards and 200,000 wolves were slaughtered in the fifty years from 1875 to 1925. Thus, it proved that the animals were no longer safe where humans lived. A new page had been turned in the story of wildlife-human encounters in South Asia.